A NAMIBIAN ELAND HUNT

(Another version of this essay appeared in Gun Digest)

After a year of preparation and planning, on June 7th 2010, I went with a colleague to Namibia to hunt plains game.

Namibia is more or less a Plains Game Hunter’s idea of Heaven: plenty of really first-rate animals, reasonable trophy fees, excellent infrastructure and a government that (so far) makes few difficulties about bringing in firearms for hunting. Unlike the Republic of South Africa, whose current firearms laws make it ever more onerous for visitors to bring in guns, Namibia understands that we are also bringing in substantial cargoes of hard currency and are very accommodating.

Namibia is more or less a Plains Game Hunter’s idea of Heaven: plenty of really first-rate animals, reasonable trophy fees, excellent infrastructure and a government that (so far) makes few difficulties about bringing in firearms for hunting. Unlike the Republic of South Africa, whose current firearms laws make it ever more onerous for visitors to bring in guns, Namibia understands that we are also bringing in substantial cargoes of hard currency and are very accommodating.

All that’s required to bring in rifles is to download a Namibian Police Services form, fill it out with the particulars of the gun(s) you’re bringing, and to present it to the police when you arrive, along with US Customs Form 4457. You fill that out before leaving the US: it serves as your proof of ownership on arrival, and is required when you return to clear US Customs. The Namibia Professional Hunters’ Association has the NPS form available on its web site, as well as a lot of very useful information not only on what and where to hunt, but including a complete set of rules and regulations applicable to hunting. Namibia has “minimum caliber” standards for different species so it pays to look these regs over carefully.

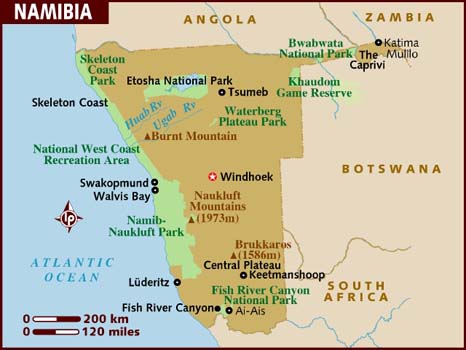

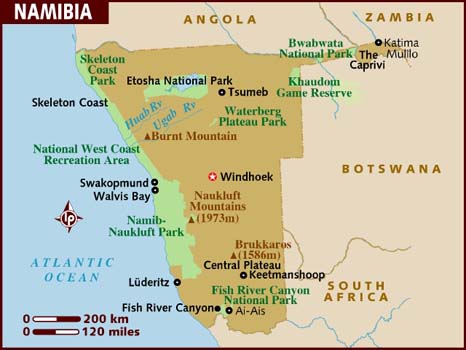

We flew from Roanoke to Windhoek, Namibia’s capital, via Detroit and Frankfurt. This was definitely the long way around, but with my typical impeccable timing I’d picked the very week that the 2010 World Cup was starting in South Africa, and tickets via Johannesburg (the usual route) weren’t to be had for less than $8000; nor were there many even at that price. When we reached Windhoek (after a 40-hour transit including a 12-hour layover in Germany) our guns were waiting for us at the Police check-in point. A very polite and cheerful officer looked at the form, compared the serial numbers on them to the physical guns, stamped the permit, and that was that. All of 10 minutes’ time, much better than the hours it can take in South Africa’s process and with none of the official surliness.

We flew from Roanoke to Windhoek, Namibia’s capital, via Detroit and Frankfurt. This was definitely the long way around, but with my typical impeccable timing I’d picked the very week that the 2010 World Cup was starting in South Africa, and tickets via Johannesburg (the usual route) weren’t to be had for less than $8000; nor were there many even at that price. When we reached Windhoek (after a 40-hour transit including a 12-hour layover in Germany) our guns were waiting for us at the Police check-in point. A very polite and cheerful officer looked at the form, compared the serial numbers on them to the physical guns, stamped the permit, and that was that. All of 10 minutes’ time, much better than the hours it can take in South Africa’s process and with none of the official surliness.

What is now called Namibia was originally settled in the 1880’s as “German Southwest Africa,” the fruit of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s ambition to participate in the Scramble For Africa as proof of Germany’s membership in The Great Powers Club. He didn’t have it long: Southwest Africa was taken by British Imperial forces in 1915; after World War One the ex-colony was administered as a “Mandated Territory” by the Union of South Africa, first under the League of Nations and later the United Nations. In 1990 South Africa bowed out of Namibian affairs, so that Namibia is one of Africa’s newest nations. Its history has left it with three commonly spoken languages (officially English, but also German and Afrikaans) in addition to various tribal tongues. From what little I saw it seems to be a reasonably prosperous and peaceful place, but no doubt there are tensions and internal divisions not visible to a foreigner who's getting the Red Carpet Treatment on his hunting holiday.

What is now called Namibia was originally settled in the 1880’s as “German Southwest Africa,” the fruit of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s ambition to participate in the Scramble For Africa as proof of Germany’s membership in The Great Powers Club. He didn’t have it long: Southwest Africa was taken by British Imperial forces in 1915; after World War One the ex-colony was administered as a “Mandated Territory” by the Union of South Africa, first under the League of Nations and later the United Nations. In 1990 South Africa bowed out of Namibian affairs, so that Namibia is one of Africa’s newest nations. Its history has left it with three commonly spoken languages (officially English, but also German and Afrikaans) in addition to various tribal tongues. From what little I saw it seems to be a reasonably prosperous and peaceful place, but no doubt there are tensions and internal divisions not visible to a foreigner who's getting the Red Carpet Treatment on his hunting holiday.

Our safari company was CEC Safaris, a small outfit located in the Omitara district, about 120 kilometers east of Windhoek, Namibia’s capital city. (The proprietor, Cornie Coetzee, has since created a new company, Cornie Coetzee Safaris in Okahandja. )

“Omitara” per se barely exists except as a name on a map: there are perhaps 700 people in the entire administrative district. Namibia has a population of only 2,200,000 people, roughly half of whom live in a few larger cities (Windhoek, Walvis Bay, Swakopmund, Luderitz and one or two others) and the rest are thinly—very thinly—scattered over an area the size of Texas and Oklahoma combined: only Mongolia has a lower population density.

Cornelius (Cornie) Coetzee is a Licensed Professional Hunter who conduct hunts all over Namibia, as well in Botswana and Zimbabwe. CEC’s lodge was called “Hunter’s Retreat.” It sits on what, by local standards, is a postage-stamp-sized piece of ground: only 2900 acres! Cornie had concession agreements with nearby ranchers who own much larger properties, to which he took his clients. The CEC lodge is a lovely place with a thatched roof, a shady porch, and a spectacular view of the grassy savannah that comprises the high central plateau of the country. However big it may seem to an American from the eastern seaboard the Retreat really is “small” in the local context. Namibian ranches are enormous, most of them larger than most US counties. The smallest ranch I hunted was bigger than the District of Columbia; many are larger than New York City. I don't know what the average is, but 100 square miles wouldn't be unusual: I hunted one place at least that big.

Namibia is the driest nation south of the Sahara, with almost no surface water. Before colonization, what population there was (both game and human) migrated in cycles from the central and southern regions, moving northwards in the dry season into what is now Angola, and back again when the rains returned. Despite its lack of surface water, there’s quite a bit underground, and the Germans brought well-drilling technology with them. Pumps supplying water year-around made colonization and livestock farming possible. The reason farm properties are so big is because when the Germans started farming they calculated how much of the very arid countryside was needed to support a single cow and staked out initial properties on that basis. It takes a lot of the scrubby central Namibian pasturage to maintain a cow!

Namibia is the driest nation south of the Sahara, with almost no surface water. Before colonization, what population there was (both game and human) migrated in cycles from the central and southern regions, moving northwards in the dry season into what is now Angola, and back again when the rains returned. Despite its lack of surface water, there’s quite a bit underground, and the Germans brought well-drilling technology with them. Pumps supplying water year-around made colonization and livestock farming possible. The reason farm properties are so big is because when the Germans started farming they calculated how much of the very arid countryside was needed to support a single cow and staked out initial properties on that basis. It takes a lot of the scrubby central Namibian pasturage to maintain a cow!

Since game animals are far more efficient at utilizing the native vegetation than domestic stock, in the intervening years there has been a transition from raising livestock back to native (and some introduced) species, because the return on investment is higher. Namibia was and still is famous for its beef, but many farms today find it more profitable to manage their land (and water resources) for wild species. Now that these no longer need to migrate in the dry season and their populations are increasing every year, trophy hunting has become a major source of foreign exchange, and the government has been very supportive of it.

Since game animals are far more efficient at utilizing the native vegetation than domestic stock, in the intervening years there has been a transition from raising livestock back to native (and some introduced) species, because the return on investment is higher. Namibia was and still is famous for its beef, but many farms today find it more profitable to manage their land (and water resources) for wild species. Now that these no longer need to migrate in the dry season and their populations are increasing every year, trophy hunting has become a major source of foreign exchange, and the government has been very supportive of it.

For the most part Namibian hunting properties are unfenced, unlike South African ranches, which are in far more populous regions and where high game fences are the rule. Some farms are high-fenced, because by law if a non-native species (such as black wildebeest) is present, it has to be confined. But many if not most ranches have fencing suitable only for cattle and goats, which wild animals don’t even notice; and which present no hindrance to their moving about freely from one property to another. In the USA we have “Deer Crossing” signs: in Namibia the equivalent is a “Kudu Crossing” sign, and we saw many kudu along the roads.

Accommodation at the Retreat was pretty luxurious. There were three guest rooms, each named

after a famous hunter: Theodore Roosevelt, J.C. Pretorius, and F.C. Selous. I had the Roosevelt

Room (above) decorated with pictures of TR, many of them from his famous 1909-1910 safari. My partner had the Selous room. We both had private bathrooms whose plumbing was based on the English System: that is to say, it provided either hot water or water pressure, but not both simultaneously. Take your pick.

Excellent meals were served in a high-ceilinged Great Room decorated with numerous taxidermy specimens. The Great Room also has a cozy sitting area around a fireplace, plus a selection of books on guns, African history, hunting, and other topics of general interest to guests. For dinner we often ate game meat. some of it was stuff we’d shot, some what the cook had in the fridge. The dishes were typical Namibian or South African style, mostly casseroles and stews. I was a little disappointed that we didn't cook anything over an open fire, but it was so cold we couldn’t sit outside after sundown. On our return at the end of each day we’d have a few drinks around the fire, settle down to dinner, and to bed immediately after, about 8:30 to 9:00. Most days we left the house at 6:00 AM, which meant about a 4:30 wake-up, a simple breakfast of rusks and coffee, and then ho! for the veld. We usually returned about 11:00 for lunch on the veranda, a nap, and then off for the evening session.

One of the blessed aspects of the Retreat—in fact one of the features that made it a true retreat—was what it lacked: television. There was a satellite antenna, but no TV’s in the guest rooms or the Great Room. This was intentional. I’m in wholehearted agreement with this philosophy of maintaining the atmosphere of a hunting camp: I don’t go to Africa to watch re-runs of American sitcoms or, worse, CNN.

And yes, “camp” is what it's called, though it certainly isn’t anything like the summer camp in which I was imprisoned for a month in 1957. There’s a saying that “The worst camp in Africa is better than the best camp in America,” and in my experience this is quite correct. True, your average African hunting camp lacks the ambience provided by numerous unwashed men drinking stale beer for a week at a time, but Africa manages to make up the deficit with good food prepared by a professional cook, daily laundry service, and comfortable beds rather than folding cots. As to pricing, this trip was definitely "top class," much nicer than my first safari. But it cost me less than I'd have paid for ten days of an Alaskan moose hunt, where I'd have been sleeping in a spike-camp tent, eating MRE's, and not changing my underwear.

Another thing the Retreat lacked was heating. That’s not a criticism: most African houses, even very nice ones, don’t have it, because most of the time they don’t need it. Their version of “winter” is like a balmy summer day in North America. Unfortunately, I managed to arrive not only as the World Cup was starting, but during the coldest spell Namibia had experienced since 1901. The cold snap hit that evening we arrived and it was—no kidding—48 degrees Fahrenheit in my room for several mornings in a row. Let me tell you, at 6:00 AM in an open hunting vehicle when the air temperature is about 30 degrees, your eyes water. Until the sun comes up you wonder how this can possibly be Africa, for God’s sake, when dying of hypothermia seems to be a greater hazard than lions or snakes. Beginning the second night, Agrippini, the maid-of-all-work, slipped a hot water bottle into each bed a half hour before we turned in, and it was very much needed and appreciated!

Of the animals I hunted on this trip, my chief quarry was an eland. The Cape or Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) is Africa’s largest antelope, a native of the south-central region of the Dark Continent. Other than giraffe, there are few non-pachyderms much larger than this wanderer of the dry savannah and grassy plains of the sub-Sahara, a beast as perfectly adapted to the arid conditions of its environment as it can be. The eland figures prominently in many tribal cultures as an symbol of endurance and patient strength, quintessential qualities needed for life in the African bush.

Of the animals I hunted on this trip, my chief quarry was an eland. The Cape or Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) is Africa’s largest antelope, a native of the south-central region of the Dark Continent. Other than giraffe, there are few non-pachyderms much larger than this wanderer of the dry savannah and grassy plains of the sub-Sahara, a beast as perfectly adapted to the arid conditions of its environment as it can be. The eland figures prominently in many tribal cultures as an symbol of endurance and patient strength, quintessential qualities needed for life in the African bush.

I rode into the field with Cornie in an amazing vehicle, his specially modified Unimog. The Unimog is made by Mercedes-Benz, a general-purpose vehicle with high ground clearance and four-wheel drive. Cornie’s was built in 1964. He took a welding torch to it, cutting off the cab, replacing it with a roll cage of his own design and construction. He added a bench seat in the rear for riders and replaced the original flat bed. As he’s modified it, it’s more or less The Mother Of All ATV’s.

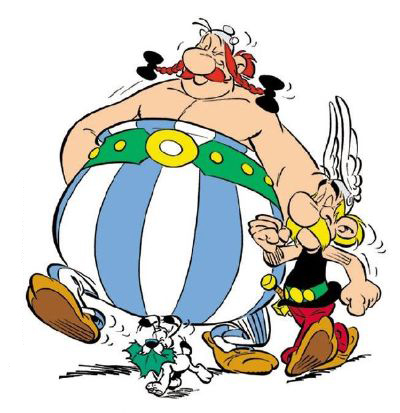

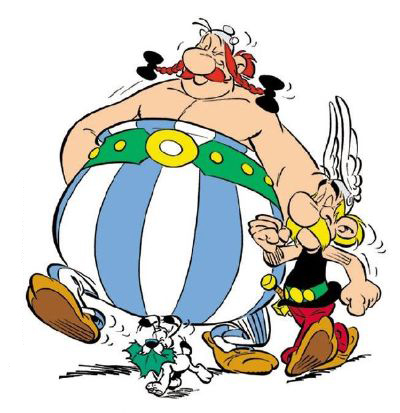

This monster has a diesel engine that honks and blats and farts black smoke when he shifts gears, but it will go absolutely anywhere. Most of the time it runs in two wheel drive, but if the sand gets soft or the slope is too steep, he can shift it into 4-wheel mode, and when he does that, I veritably believe the Unimog would climb a tree. It sounds like a tank, and even at a walking pace, the local game wouldn’t let it get within 400 yards, fleeing before the racket it makes: but it served us admirably. Naturally there’s a winch in the back for hauling in the larger examples of  dead ungulates. It has an on-board air compressor, miscellaneous digging and chopping tools, and a jerry can of water, among other odds and ends. And it has a name: “Obelisk,” after a cartoon character in the old Asterix The Gaul comic books. There’s a distinct family resemblance between him and Cornie’s Unimog.

dead ungulates. It has an on-board air compressor, miscellaneous digging and chopping tools, and a jerry can of water, among other odds and ends. And it has a name: “Obelisk,” after a cartoon character in the old Asterix The Gaul comic books. There’s a distinct family resemblance between him and Cornie’s Unimog.

I rode in the passenger seat with a rifle in the rack in front; France, the tracker, rode in the back. France is a man of few words (none of them in English) but amazing eyesight and keen tracking ability. Between them, Cornie and France kept this greenhorn safe and saw to it that I had a great hunt. We would cruise the roads on the concessions, looking for game: when something was spotted we’d dismount and start walking and stalking. This is essentially the way Teddy Roosevelt did things in 1909, though of course he used a horse instead of hulking, oversized quasi-Jeep.

The first day was a bust, largely because I didn’t have a clue what was going on. Cornie and France had spotted a set of fresh eland tracks, so we descended from the Unimog, and set off following them. What we were doing made little sense to me at the time, because there was no way this city kid could see what they were seeing: but they could read those scuff marks in the dirt like they were reading highway signs. This despite the fact that there were innumerable ones made by many animals, not just the band of fugitive putative eland we were chasing.

The first day was a bust, largely because I didn’t have a clue what was going on. Cornie and France had spotted a set of fresh eland tracks, so we descended from the Unimog, and set off following them. What we were doing made little sense to me at the time, because there was no way this city kid could see what they were seeing: but they could read those scuff marks in the dirt like they were reading highway signs. This despite the fact that there were innumerable ones made by many animals, not just the band of fugitive putative eland we were chasing.

I scrambled after them as best I could for about an hour, wondering what in the hell was happening. Now, I’m not the fleetest of foot: I can manage a respectable waddle when pressed, but they set a hot pace and I had a hard time keeping up, because I had to watch my footing as well as try to avoid the thorns on the vegetation. Everything that grows in Namibia has thorns, except the waist-high grass that conceals loose rocks over which a tubby and out-of-shape university professor would occasionally stumble (and snakes: Cornie swore he saw several, but thank God I never did). Furthermore, knowing that there thorns in abundance, I’d cleverly chosen a pair of briar proof hunting pants to wear. I’d thought this was a good idea, but the facing on the pants was very hard and made a lot of noise as I scraped through the bushes. So did I when I periodically knocked over a rock or tripped on something. These incidents caused Cornie to turn and look at me sternly, and though he didn’t actually say, “Shut up, you clumsy greenhorn!” I could tell he was thinking it, and only his professionalism prevented him from doing so. But in fact I was a clumsy greenhorn, and I simply had no idea why we were racing through the brush at (literally) breakneck speed.

Two hours of the chase fair winded me, but I needed to learn. Back at the camp for lunch I asked him what we’d been doing that morning, because obviously I’d missed the point; and also to tell me everything I’d done wrong. He was diplomatic enough to ignore the second question, but explained that, “We were tracking a herd of eland, not stalking them. At one point we came within a hundred yards: didn’t you hear them?” Well, to be honest, about all I could hear was my panting and the thumping of my elderly heart, but if he says we got that close, we got that close. I certainly never saw them. I don’t think he did, either, but he knew they were there, from their tracks.

This business of tracking is an acquired skill that has to be learned from early childhood. My boyhood in Da Bronx didn’t prepare me for it, nor to be honest have I developed much skill at it in hunting in the USA, mainly because I never needed to. (On the one occasion when I really did need to do it, I failed miserably.) But Cornie grew up in the veld. He can not only tell what kind of animal he’s tracking, he can tell you which specific animal it is and how many individual animals there are in the group; how long ago they passed; what sex the one he’s following is; how big its horns are; and probably what it had for breakfast on the previous Tuesday. In the course of the hunt, periodically he or France would spot the tracks of some animal. Cornie would slam on the brakes of the Unimog, and off we’d go, haring after whatever it was. That afternoon after the fruitless eland chase we tried stalking impala twice, but never got a shot.

Day Two was much better. On the second morning we had tried for impala again, with no luck. But driving across one of the farms we encountered another group of hunters at the crest of a ridge: their PH said he’d seen some eland in the valley below. Cornie took a look with his binoculars, returned to the Unimog, and said, “Let’s go!” I dismounted from Obelisk and off the three of us went.

First we had to get downwind of the eland, which took some time. The wind was blowing from our right, so we moved quietly down into the valley, making a very long detour to our left. I don’t know how far we went, but it had to be half a mile or more before we turned back to the right, heading upwind towards the herd. The actual stalk began at that point, and we spent the next half hour or so getting into position.

We finally came within sight of three big bulls forming a bachelor group. Cornie said, “The one in the middle! He’s very large and old, take him!” We were perhaps 180 yards from them, across an open area, and didn’t dare get any closer. Cornie set up his shooting sticks and I got ready to shoot.

The middle bull turned broadside to me, facing to my right; I fired at him, and he began to trot. “Shoot again! He’s still on his feet!” Cornie shouted, so I did. I saw the impact of the second bullet, but had failed to see the dust raised by my first hit. About two seconds after the second shot, the bull fell over and dropped out of sight in a small depression. “You got him!” I was told, and we walked up to the spot, with France looking sharply about.

I spotted the bull first, down on his left side, and apparently stone dead. “Don’t get near his horns!” Cornie warned me. “Make sure he’s dead!”

He was. He was deader than Disco. The first shot had killed him, the second was merely insurance. He was a Dead Eland Walking without realizing it when the second bullet hit. The first took him high on the right side, and coursed through both lungs, coming to rest just under the skin on the left side.  The bull was about 12 years old judging by his teeth, which put him well past his prime. Cornie (whose philosophy is to shoot only mature males) was delighted with the kill. Even better, the white stripes on his side marked him as a “Livingstone Eland,” a subspecies found in this part of the native range that tends to run bigger than most

The bull was about 12 years old judging by his teeth, which put him well past his prime. Cornie (whose philosophy is to shoot only mature males) was delighted with the kill. Even better, the white stripes on his side marked him as a “Livingstone Eland,” a subspecies found in this part of the native range that tends to run bigger than most  Common Eland. And this one was a real bruiser: about 850 kilos.

Common Eland. And this one was a real bruiser: about 850 kilos.

As the saying goes, once the trigger is pulled the fun is over and the work begins: but fortunately in Africa there’s always someone around to do the grunt work for The Client. Obelisk is equipped with a winch that was up to the job, and a ramp that looks like it was made from a farm gate. Supervised by Snip, Cornie’s tracking dog (who made sure the eland didn’t spring to life and kill us all) France and Cornie managed to get a cable around the beast and haul him up into the bed. He hung over the end quite a bit. It took only about an hour or so to get him into the back and head off for the skinning shed.

The Namibian Professional Hunting Association has a series of award levels for various species, based on the Safari Club measurements. A “Gold Medal” trophy requires a minimum of 211 points: my bull came in at 217. With horns that big and a head the size of my Labrador Retriever, I had no room to put a shoulder mount (nor would my wife have tolerated it…) so opted for a European style skull mount. This came out very well. my wife says it looks like a 3-D version of a Georgia O’Keefe painting.

The Namibian Professional Hunting Association has a series of award levels for various species, based on the Safari Club measurements. A “Gold Medal” trophy requires a minimum of 211 points: my bull came in at 217. With horns that big and a head the size of my Labrador Retriever, I had no room to put a shoulder mount (nor would my wife have tolerated it…) so opted for a European style skull mount. This came out very well. my wife says it looks like a 3-D version of a Georgia O’Keefe painting.

I was using my sweet little 1944-vintage Husqvarna sporter in 8x57JS (8mm Mauser). This rifle is built on a Swedish-made Model 1896 Mauser action: it’s not a converted military rifle, but a commercial sporter intended for the domestic market (there wasn’t much of an export market in 1944). It’s one of the last sporters Husqvarna made on this action: production ceased in 1944 and when it resumed a few years after World War Two, Husqvarna began using Model 1898 actions purchased from FN.

While the Model 1898 Mauser is far and away the most successful bolt action used for sporting guns, I’ve always preferred the Model 1896. These trim little rifles make very well-balanced sporting guns that are sleeker and daintier than the somewhat porky Model 1898. Americans tend to dislike the cock-on-closing feature of the pre-Model 1898 Mausers, but it makes for a thinner, lighter, and simpler bolt. Nor am I the least bit bothered by the lack of the so-called “safety lug” of the Model 1898. The 1896 is amply strong for the calibers in which it’s chambered and any caliber  that’s hot enough to require a safety lug is too hot for my taste, thank you very much.

that’s hot enough to require a safety lug is too hot for my taste, thank you very much.

I chose the rifle and the caliber because I was going to be hunting in a former German colony and so it seemed appropriate; quite aside from that the 8x57 is one of the truly great hunting rounds, an exceptionally good all-around bushveld caliber. That it isn’t more widely used here and in Africa is a shame, but the overwhelming predominance of American companies in the sporting gun market has meant that American caliber preferences have become world-wide ones, and the 8x57 has sort of fallen by the wayside.

The 8x57 is under loaded by American ammunition companies, who are concerned lest it be used in the relatively weak Gewehr 88 "Commission" rifles, of which there are many still in use. Our companies load it to about well below the performance of the .30-40 Krag. A 170 or 175-grain bullet at 2100-2200 FPS is no great shakes but it’s adequate for most North American game: I used Remington’s product to make one-shot kills on a feral hog and a big whitetail buck.

The 8x57 is under loaded by American ammunition companies, who are concerned lest it be used in the relatively weak Gewehr 88 "Commission" rifles, of which there are many still in use. Our companies load it to about well below the performance of the .30-40 Krag. A 170 or 175-grain bullet at 2100-2200 FPS is no great shakes but it’s adequate for most North American game: I used Remington’s product to make one-shot kills on a feral hog and a big whitetail buck.

However, African animals, even non-dangerous ones, are very tough and require a lot of killing power. The 8x57 is capable of performance every bit as good as the .30-06 and .308. Norma loads it with a 196-grain bullet at 2526 FPS and 2778 F-P of energy (3764 Joules, well above the Namibian government’s mandated minimum energy of 2700 joules for eland). This puts it in the same power league as the .30-06.

I used Norma’s “Alaska” bullet (above, right) on the eland. This bullet is designed for large North American animals (as the name implies) and is somewhat less suited to African game than the very similar but stronger Norma “Oryx” bullet. The “Oryx” ammunition has identical ballistics: I used some of it on other species. Back at the skinning shed we retrieved the killing bullet, just under the hide on the far side of the animal. It had shed half its weight—not optimal performance. Perhaps the “Oryx” bullet would have been a better choice, and likely would have gone all the way through; but I happened to have the box of “Alaskas” that day and the job got done.

Photo of the night sky over the Retreat, my sincere thanks to Matt Gore

I will go back: in fact I went again in July of 2013, when I took an elephant in the Caprivi Strip. My partner for this trip also went and killed a buffalo.

Really, there is only one reason not to hunt in Africa: it spoils you for anywhere else.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |

Namibia is more or less a Plains Game Hunter’s idea of Heaven: plenty of really first-rate animals, reasonable trophy fees, excellent infrastructure and a government that (so far) makes few difficulties about bringing in firearms for hunting. Unlike the Republic of South Africa, whose current firearms laws make it ever more onerous for visitors to bring in guns, Namibia understands that we are also bringing in substantial cargoes of hard currency and are very accommodating.

Namibia is more or less a Plains Game Hunter’s idea of Heaven: plenty of really first-rate animals, reasonable trophy fees, excellent infrastructure and a government that (so far) makes few difficulties about bringing in firearms for hunting. Unlike the Republic of South Africa, whose current firearms laws make it ever more onerous for visitors to bring in guns, Namibia understands that we are also bringing in substantial cargoes of hard currency and are very accommodating. We flew from Roanoke to Windhoek, Namibia’s capital, via Detroit and Frankfurt. This was definitely the long way around, but with my typical impeccable timing I’d picked the very week that the 2010 World Cup was starting in South Africa, and tickets via Johannesburg (the usual route) weren’t to be had for less than $8000; nor were there many even at that price. When we reached Windhoek (after a 40-hour transit including a 12-hour layover in Germany) our guns were waiting for us at the Police check-in point. A very polite and cheerful officer looked at the form, compared the serial numbers on them to the physical guns, stamped the permit, and that was that. All of 10 minutes’ time, much better than the hours it can take in South Africa’s process and with

We flew from Roanoke to Windhoek, Namibia’s capital, via Detroit and Frankfurt. This was definitely the long way around, but with my typical impeccable timing I’d picked the very week that the 2010 World Cup was starting in South Africa, and tickets via Johannesburg (the usual route) weren’t to be had for less than $8000; nor were there many even at that price. When we reached Windhoek (after a 40-hour transit including a 12-hour layover in Germany) our guns were waiting for us at the Police check-in point. A very polite and cheerful officer looked at the form, compared the serial numbers on them to the physical guns, stamped the permit, and that was that. All of 10 minutes’ time, much better than the hours it can take in South Africa’s process and with  What is now called Namibia was originally settled in the 1880’s as “German Southwest Africa,” the fruit of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s ambition to participate in the Scramble For Africa as proof of Germany’s membership in The Great Powers Club. He didn’t have it long: Southwest Africa was taken by British Imperial forces in 1915; after World War One the ex-colony was administered as a “Mandated Territory” by the Union of South Africa, first under the League of Nations and later the United Nations.

What is now called Namibia was originally settled in the 1880’s as “German Southwest Africa,” the fruit of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s ambition to participate in the Scramble For Africa as proof of Germany’s membership in The Great Powers Club. He didn’t have it long: Southwest Africa was taken by British Imperial forces in 1915; after World War One the ex-colony was administered as a “Mandated Territory” by the Union of South Africa, first under the League of Nations and later the United Nations.

Namibia is the driest nation south of the Sahara, with almost no surface water. Before colonization, what population there was (both game and human) migrated in cycles from the central and southern regions, moving northwards in the dry season into what is now Angola, and back again when the rains returned. Despite its lack of surface water, there’s quite a bit underground, and the Germans brought well-drilling technology with them. Pumps supplying water year-around made colonization and livestock farming possible. The reason farm properties are so big is because when the Germans started farming they calculated how much of the very arid countryside was needed to support a single cow and staked out initial properties on that basis. It takes a lot of the scrubby central Namibian pasturage to maintain a cow!

Namibia is the driest nation south of the Sahara, with almost no surface water. Before colonization, what population there was (both game and human) migrated in cycles from the central and southern regions, moving northwards in the dry season into what is now Angola, and back again when the rains returned. Despite its lack of surface water, there’s quite a bit underground, and the Germans brought well-drilling technology with them. Pumps supplying water year-around made colonization and livestock farming possible. The reason farm properties are so big is because when the Germans started farming they calculated how much of the very arid countryside was needed to support a single cow and staked out initial properties on that basis. It takes a lot of the scrubby central Namibian pasturage to maintain a cow! Since game animals are far more efficient at utilizing the native vegetation than domestic stock, in the intervening years there has been a transition from raising livestock back to native (and some introduced) species, because the return on investment is higher. Namibia was and still is famous for its beef, but many farms today find it more profitable to manage their land (and water resources) for wild species. Now that these no longer need to migrate in the dry season and their populations are increasing every year, trophy hunting has become a major source of foreign exchange, and the government has been very supportive of it.

Since game animals are far more efficient at utilizing the native vegetation than domestic stock, in the intervening years there has been a transition from raising livestock back to native (and some introduced) species, because the return on investment is higher. Namibia was and still is famous for its beef, but many farms today find it more profitable to manage their land (and water resources) for wild species. Now that these no longer need to migrate in the dry season and their populations are increasing every year, trophy hunting has become a major source of foreign exchange, and the government has been very supportive of it.

Of the animals I hunted on this trip, my chief quarry was an eland. The Cape or Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) is Africa’s largest antelope, a native of the south-central region of the Dark Continent. Other than giraffe, there are few non-pachyderms much larger than this wanderer of the dry savannah and grassy plains of the sub-Sahara, a beast as perfectly adapted to the arid conditions of its environment as it can be. The eland figures prominently in many tribal cultures as an symbol of endurance and patient strength, quintessential qualities needed for life in the African bush.

Of the animals I hunted on this trip, my chief quarry was an eland. The Cape or Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) is Africa’s largest antelope, a native of the south-central region of the Dark Continent. Other than giraffe, there are few non-pachyderms much larger than this wanderer of the dry savannah and grassy plains of the sub-Sahara, a beast as perfectly adapted to the arid conditions of its environment as it can be. The eland figures prominently in many tribal cultures as an symbol of endurance and patient strength, quintessential qualities needed for life in the African bush.

dead ungulates. It has an on-board air compressor, miscellaneous digging and chopping tools, and a jerry can of water, among other odds and ends. And it has a name: “Obelisk,” after a cartoon character in the old Asterix The Gaul comic books. There’s a distinct family resemblance between him and Cornie’s Unimog.

dead ungulates. It has an on-board air compressor, miscellaneous digging and chopping tools, and a jerry can of water, among other odds and ends. And it has a name: “Obelisk,” after a cartoon character in the old Asterix The Gaul comic books. There’s a distinct family resemblance between him and Cornie’s Unimog.  The first day was a bust, largely because I didn’t have a clue what was going on. Cornie and France had spotted a set of fresh eland tracks, so we descended from the Unimog, and set off following them. What we were doing made little sense to me at the time, because there was no way this city kid could see what they were seeing: but they could read those scuff marks in the dirt like they were reading highway signs. This despite the fact that there were innumerable ones made by many animals, not just the band of fugitive putative eland we were chasing.

The first day was a bust, largely because I didn’t have a clue what was going on. Cornie and France had spotted a set of fresh eland tracks, so we descended from the Unimog, and set off following them. What we were doing made little sense to me at the time, because there was no way this city kid could see what they were seeing: but they could read those scuff marks in the dirt like they were reading highway signs. This despite the fact that there were innumerable ones made by many animals, not just the band of fugitive putative eland we were chasing.

The bull was about 12 years old judging by his teeth, which put him well past his prime. Cornie (whose philosophy is to shoot only mature males) was delighted with the kill. Even better, the white stripes on his side marked him as a “Livingstone Eland,” a subspecies found in this part of the native range that tends to run bigger than most

The bull was about 12 years old judging by his teeth, which put him well past his prime. Cornie (whose philosophy is to shoot only mature males) was delighted with the kill. Even better, the white stripes on his side marked him as a “Livingstone Eland,” a subspecies found in this part of the native range that tends to run bigger than most  Common Eland. And this one was a real bruiser: about 850 kilos.

Common Eland. And this one was a real bruiser: about 850 kilos.  The Namibian Professional Hunting Association has a series of award levels for various species, based on the Safari Club measurements. A “Gold Medal” trophy requires a minimum of 211 points: my bull came in at 217. With horns that big and a head the size of my Labrador Retriever, I had no room to put a shoulder mount (nor would my wife have tolerated it…) so opted for a European style skull mount. This came out very well. my wife says it looks like a 3-D version of a Georgia O’Keefe painting.

The Namibian Professional Hunting Association has a series of award levels for various species, based on the Safari Club measurements. A “Gold Medal” trophy requires a minimum of 211 points: my bull came in at 217. With horns that big and a head the size of my Labrador Retriever, I had no room to put a shoulder mount (nor would my wife have tolerated it…) so opted for a European style skull mount. This came out very well. my wife says it looks like a 3-D version of a Georgia O’Keefe painting.

that’s hot enough to require a safety lug is too hot for my taste, thank you very much.

that’s hot enough to require a safety lug is too hot for my taste, thank you very much.  The 8x57 is under loaded by American ammunition companies, who are concerned lest it be used in the relatively weak Gewehr 88 "Commission" rifles, of which there are many still in use. Our companies load it to about well below the performance of the .30-40 Krag. A 170 or 175-grain bullet at 2100-2200 FPS is no great shakes but it’s adequate for most North American game: I used Remington’s product to make one-shot kills on a feral hog and a big whitetail buck.

The 8x57 is under loaded by American ammunition companies, who are concerned lest it be used in the relatively weak Gewehr 88 "Commission" rifles, of which there are many still in use. Our companies load it to about well below the performance of the .30-40 Krag. A 170 or 175-grain bullet at 2100-2200 FPS is no great shakes but it’s adequate for most North American game: I used Remington’s product to make one-shot kills on a feral hog and a big whitetail buck.