HERE'S WHERE I GET INTO TROUBLE

My experiences from two African hunting trips to date, one with a .30-06 and one with the 8x57, along with discussion with PH's of my acquaintance and personal observation, have convinced me that for almost any African plains game species, nothing “better” than those two calibers is needed. A number of PH’s I know have forcefully asserted that they wince when a hunter arrives with a high-velocity, light-bullet Super-Something Magnum. To these experienced pros, such calibers mean potential trouble and disappointment. Any of them would much prefer to have a client arrive with a humdrum, work-a-day .30-06 than anything else.

American hunters are obsessed with velocity above all other qualities and tend to look with disfavor on mundane calibers throwing heavy bullets at medium speed. Such calibers are not Sexy. They are not likely to attract attention at the range. They have not been sanctified by endless praise from gun writers (who are paid to sell guns and ammunition, not to point out the actual truth about the good and bad points of equipment and calibers that are advertised in their magazines).

To 99.9% of American hunters, Faster = Better, and don't you ever forget it.

But the fact of the matter—as those PH’s will tell you, and no matter what hooey the ammunition companies and their lackeys in the gun press publish about “energy dumping” and “hydrostatic shock” and similar irrelevancies—that for large animals, especially large African animals penetration is what kills, and is by far the most important measure of performance.

BUT FASTER ISN'T BETTER

A 7mm Super-Duper Mangle-‘Em may have eye-popping ballistics on paper but not be a good choice for Africa. African antelope are mostly big critters, and they’re built tough. Getting a bullet into one of them deeply enough to hit a vital structure is an absolute necessity to effect a clean kill. Any caliber whose main selling point is bullet speed, not bullet mass, isn't going to be as effective as paper figures or even experience on North American animals might lead someone to think.

Probably for 90+% of Americans, whitetail deer are the biggest game they have ever encountered. Some will have hunted moose and some will have hunted elk. None of these compares to a blue wildebeest or an eland in any respect except size. The bison is probably the only North American mammal that remotely compares to large African game in terms of body size and bone structure, and few of us hunt those.

Probably for 90+% of Americans, whitetail deer are the biggest game they have ever encountered. Some will have hunted moose and some will have hunted elk. None of these compares to a blue wildebeest or an eland in any respect except size. The bison is probably the only North American mammal that remotely compares to large African game in terms of body size and bone structure, and few of us hunt those.

The whitetail is a fragile creature not tenacious of life: rarely will one reach 200 pounds live weight in most parts of the USA. Anything from a .30-30 on up is going to kill whitetails reliably, as vast experience has shown. Elk are much tougher and larger but they’re still deer: they aren’t very heavily constructed and bullets from a high-speed rifle usually have enough punch to reliably kill one. Many an elk has been killed with lightweight bullets from calibers like the .270 Winchester. Moose are big, but they’re not very hard to kill, and many have been killed with “deer rifle” calibers like the .30-30. The classic calibers for bison are the .45-70 to .45-110: hardly speed demons.

MOMENTUM IS THE REASON WHY

Far more important in a good African hunting caliber than energy is the concept of momentum. Momentum is what keeps the bullet moving in a straight line after it encounters resistance. Momentum is what enables the bullet to get through the tough hide, the heavy muscles, and the dense bone structure of big animals. Momentum is the product of bullet mass times velocity.

Energy increases with the square of the velocity

E=MV2/2

Which is why a relatively moderate increase in speed produces a really large increase in paper energy.

But momentum is in direct proportion to both velocity and mass:

M= MV

The relationship of bullet weight and momentum is linear, as is the relationship of bullet speed and momentum. All  else being equal, a heavy bullet has higher momentum than a lighter one. A bullet may have lots of energy but if it lacks momentum it cannot effectively translate that energy into adequate penetration.

else being equal, a heavy bullet has higher momentum than a lighter one. A bullet may have lots of energy but if it lacks momentum it cannot effectively translate that energy into adequate penetration.

Consider the way a building is demolished using a wrecking ball: this is a prime example of how momentum matters. A wrecking ball weighing, say, 3200 pounds, and moving at a very lazy velocity of perhaps 22 FPS (15 MPH) has a substantial amount of kinetic energy: 24,200 FP. But what knocks out a square yard of solid masonry at a time isn't the energy of that ball, it's the momentum, which is 32000 FP. It takes a lot of mass to stop something that heavy, even moving at a very slow speed. It's going to make short work of that building.

The same principle applies to a bullet.

Let's compare the energy of that wrecking ball to that of, say, a 540 grain bullet from a .505 Gibbs moving at 2300 FPS (about as much gun as any normal human can fire off the shoulder). That bullet has a whopping amount of kinetic energy: 6345 FP. It's momentum is 177.4 FP. In the context of hunting, the .505 Gibbs is on humongous Mother of a rifle, adequate for anything on this planet. But (even if it were economically feasible) it would be take a very, very long time to knock down the building by shooting at it. It's the momentum of the ball that brings the building down, not its energy.

If we extrapolate from this admittedly extreme example, we have to conclude that hunting calibers for big animals need high levels of momentum, and that energy is a secondary consideration in caliber selection.

JUMPING OFF THE PRECIPICE...

Now, I'm going to offend a lot of people here. Nothing illustrates this principle better than the use of the .270 Winchester on African game. The .270 is an outstanding round for North American hunting of medium-sized animals: it has no peer as a rifle for sheep, and it's unquestionably effective on deer. But it's too light for big stuff, and in Africa nearly everything qualifies as big stuff.

Many Americans who own and dearly love their .270's bring them to Africa and use them with a fair degree of success: but while there probably isn't any hard data on the rate of animals lost with this caliber compared to others, my own experience has shown me that it's marginal at best.

Like the .243 in North America, in Africa the .270 is a gun for experts, because its killing effectiveness depends on perfect bullet placement. As we all know, perfect placement isn't always achieved. Let's look at some numbers.

BY THE NUMBERS

Using Norma’s published figures as a basis, we can calculate that the .30-06 with a 180 grain bullet at 2700 FPS has a “momentum number” of 69.4 FP. The .30-06 with a 200-grain bullet has a momentum of 75 FP. Some manufacturers load a 220-grain bullet in this caliber.

We can take these figures as a “yardstick” measure of a caliber whose performance is adequate for plains game and has been proven over many, many years of use.

The 130-grain bullet of the .270 Winchester at the very high velocity of 3140 FPS has a paper energy of 2847 FP. But its momentum is only 58.3 FP. Compare this to the dull-as-ditchwater 8x57, whose praises Jack O'Connor never sang, and which is hardly known in the USA except as cheap milsurp hardball for plinking. Norma's 196-grain 8mm bullet moving at 2526 FPS—600 FPS slower than that .270— has a paper energy of 2778 FP, very comparable; but its momentum figure is 77.8 FP, better even than our "yardstick" 180-grain .30-06. The very much higher velocity of the .270's light bullet gives it no advantage over the plodding 8x57's heavy one. The experience of those who have used the .270 on larger antelope will bear out that it's not as effective as the .30-06 or the 8x57.

OK, LOAD HEAVIER BULLETS IN THE .270, THEN!

Repeat: it’s not energy that matters most, it’s momentum: that is, the tendency of the bullet to resist deflection. Heavily constructed bullets with high momentum penetrate deeply to reach important structures. Well, OK, the .270 can be had with heavier bullets. What happens then?

The heaviest bullet Norma lists for the .270 is 156 grains at 2854 FPS. This load has 2822 FP of energy, close to that of the 8x57. But its momentum is only 63.6 FP, still less than that of the .30-06 and substantially inferior to the 8x57. Even with the heaviest bullet available, the .270 falls short. However stellar a performer it may be on deer, it’s not enough for reliably making one-shot kills on, say, wildebeest, let alone something bigger.

THE BULLETS THEMSELVES MAY BE ANOTHER PROBLEM

SECTIONAL DENSITY:

Another factor in the equation is the bullets typically needed to attain dazzling velocity numbers. To achieve the high speeds lightweight bullets have to be used.

Compare the velocities given above for the .270 using the 130-grain bullet (3140 FPS) and the 156-grain bullet (2854 FPS). It will be obvious that the heavier bullet has the higher momentum despite moving some 300 FPS slower...and it's still well below the .30-06 or the 8x57. Furthermore, that 130 grain bullet has a much lower sectional density (SD). SD is the ratio of weight to cross sectional diameter. High SD translates to higher momentum and retained energy down range. Lightweight fast bullets don't give an edge at long range because they don't have enough SD to retain velocity over long distances...i.e., their momentum is low.

To achieve high velocity you must use light bullets: but light bullets have low sectional density. It can’t be otherwise: since the bullet's diameter can't change, weight goes down, so does SD. Sure, velocity increases, but this doesn't make up for the lack of mass: and when you push the bullet too fast you run into the issue of bullet fragility and the tendency of lightweight projectiles to break up on impact. If you toughen the jacket to resist break-up, you get lower sectional density for the same length because copper weighs less than lead. Lower sectional density is exactly the opposite of what’s needed.

STABILIZATION

Of course it's possible to make a bullet of any desired weight in any desired diameter: but then there are issues with how fast it has to be spun to be stabilized in flight. Most sporting rifles use long-established "standard" twist rates that will stabilize bullets falling within a reasonably generous range of weights (and hence SD's). If you make the bullet very long (and hence heavier) so as to maintain SD, stability suffers because beyond a certain length, standard rifling twists won't spin it fast enough to stabilize it. A typical twist rate for the .270 and similar calibers is 1 turn in 10 inches: this is fine for the range of bullets it shoots. But the twist rate is based on bullet diameter and length, not weight, using the Greenhill formula. To make a heavier bullet while holding the diameter fixed, it has to be made longer. At some point it becomes too long for the rifling to stabilize.

There's no way out of the trap: hypervelocity requires light bullets. Increase the weight and retain the diameter and accuracy goes over the side. A look at any manufacturer's charts will show you the range of weights available in any given caliber—they'll all be the same because everyone uses the same rifling twists.

BULLET CONSTRUCTION

Light weight goes hand in hand with fragile construction. A fragile, fast-moving bullet that encounters the heavy bones typical of a large animal will be prone to breaking up on impact. It can’t achieve the deep penetration needed to reach vital organs protected by those bones: striking a massive humerus or scapula will inevitably cause it to break up, achieving at best a relatively shallow wound. What it’s not likely to do is penetrate those bones in a straight line, entering the chest and striking the heart and lungs behind them. That's what high SD and high momentum allow a properly-designed bullet to do.

The only way to solve this conundrum is to have a bullet that is adequately constructed to remain more or less intact while punching through to the vitals; and to move that bullet at a speed that will give it enough momentum to do so.

SHOT PLACEMENT

Well, what about shot placement? Without doubt this is the key to success no matter what you shoot or are shooting at. American hunters are trained to shoot behind the shoulder so that the bullet will enter the chest cavity to reach the heart and/or lungs. Fine and good, and this tactic works really well on North American animals, even moose and elk, because despite large size these creatures don’t have bones as heavy as those of big antelope. A fast-stepping Super-Duper Mangle’Em will invariably give good results if the bullet is placed where it isn’t likely to encounter heavy bone structure: between the ribs is a good choice. But the ribs of a most African antelope are sufficiently massive that light bullets, even if they don’t break up, will often be deflected off the straight line to the vital organs.

PH's don't like "boiler room" shots. They will usually advise you to aim for the shoulder: "Come up the leg to one-third of the body depth, that's where the heart is and that's where your bullet should go."You can see examples of how the bullets should be placed in the fine book The Perfect Shot, by Kevin Robertson, a noted African PH and veterinarian. The heart/shoulder shot is almost always recommended as the surest and most reliable way by this very experienced professional, and by every other PH I've talked this issue over with.

Sure, a lung hit will kill every time, but it may also involve a long tracking job. The heart shot not only insures death (if the bullet penetrates deeply enough) but by breaking the bones of the shoulder it immobilizes the beast, or at least impairs his capacity to run. A wounded antelope with four intact legs can run a long, long way. Breaking a shoulder joint up will usually bring him down very quickly.

USE ENOUGH GUN

The answer to the hunter's dilemma in Africa is...may I have the envelope please?...heavy, toughly constructed bullets at moderate velocities, and that's what every PH will advise you to use if you ask him. Most PH's will carry something like a .375 H&H or a .416 as a working rifle. Some will use the .300 Winchester Magnum. But you will be hard pressed to find any one of them using a .270 as his all-around gun.

HISTORY

More than a century and a half of regular use in Africa has shown beyond doubt that adequately stabilized, heavy-for-caliber bullets (i.e., those with high sectional density and high momentum) moving at moderate speeds kill far better than their paper ballistics might predict to be the case.

To take another example: the .303 British has a long and distinguished record as a hunting caliber in Africa. Of course, a historical reason for its popularity is that it was military issue: farmers and ranchers who grew up in the veld always used what was most readily available. In most places this meant the .303 or the 8x57. These people grew up with Enfields or Mausers in their hands, understood them thoroughly, knew how to shoot them well, and knew what they would and wouldn’t do on game animals.

Why do they work so well? We've looked at the numbers for the 8x57, what about the .303? With the 215-grain bullet used in the Marks III through VI in this caliber, the .303 has a momentum of 74.9 FP; it drops to 64 with the 175-grain military-issue Mark VII Ball ammunition, comparable to the .30-06 with a similar weight of bullet. The latter round was—and still is—widely used. (It has a reputation as a real killer not only due to its high momentum but to the design of the bullet, which makes it yaw on contact with flesh. It penetrates well and anyone who's used it  on game will tell you about the remarkable size of the exit wounds it creates.)

on game will tell you about the remarkable size of the exit wounds it creates.)

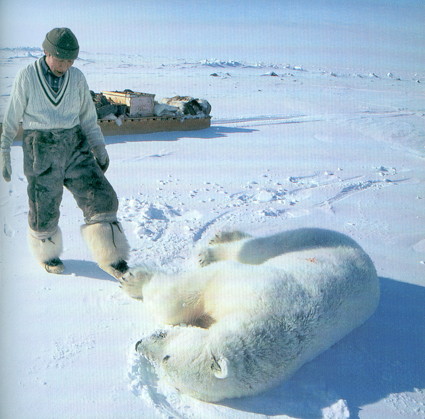

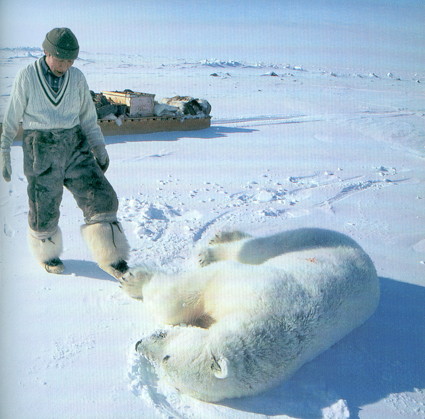

Some years ago National Geographic published the photos shown here of an Inuit hunter taking a full grown polar bear (the largest animal in North America) with a Lee-Enfield #4 rifle in .303 British. There was no informatiuon regarding the ammunition he used, but I would be very surprised if it were anything but the military-issue Mark VII round. The Canadian government still issues No. 4's to the "Arctic Rangers," a local militia force, and since that's what they have, that's what they use for hunting big stuff. This wasn't the first time man had taken a polar bear with his .303, either. As the image above right shows, this was a successful shot; according to National Georgraphic, it was a one-shot kill. It goes to show you what an experienced hunter who thoroughly  understands his rifle and his quarry can do what needs to be done.

understands his rifle and his quarry can do what needs to be done.

In Africa the .303 using a 215-grain bullet found great favor with individuals hunting really big stuff, like elephant. Yes, elephant. No one in his senses would hunt elephant today with a .303, but it has been done, and not just by Karamojo Bell in the 19th Century. Look back at the picture of CEC's Great Room: that elephant tusk hanging over the fireplace was collected by Cornie's father in the 1950's He killed it with the military-issue SMLE hanging below the tusk. It wasn’t the only elephant he took with it, either. There is no doubt that many elephant are still taken with .303's today by those who have no other rifle. Momentum, momentum, momentum. That's what makes it work.

BRING SOMETHING OTHER THAN A .270 IF YOU HUNT IN AFRICA

The .270 is marginal at best as an all-around caliber in Africa. I've seen it in action and base my opinion on what I've personally witnessed. I have no doubt it gives sterling service on warthog or impala or springbok, or anything in the same size range; and that in the hands of an expert and a cool, calm shot—adjectives that usually don't apply to visitors on a once-in-a-lifetime safari—it will kill bigger animals, but too often it doesn't do so outright. It almost always will require a follow-up on such creatures as wildebeest: only a madman would use it on a Cape buffalo, and it likely wouldn't penetrate the inch-and-a-half-thick hide of an old bull giraffe.

EYEWITNESS REPORT

On two separate safaris I hunted with partners who used the .270 on plains game. Neither of them made one-shot kills even on medium sized animals such as blesbok and hartebeest. One of these gentlemen is a far better marksman than I am, but his kills always required a coup de grace. The other lost a magnificent kudu using his .270. Oh, he hit the animal, and it eventually died (they found the carcass a week later) but the bullet, entering the tough musculature of the brisket, simply blew a superficial hole without penetrating the chest cavity. That would almost certainly not have happened had he shot that kudu with something firing heavier bullets. He paid for that kudu, and the kudu paid dearly for his choice of calibers: it probably took him several days to die. He eventually killed another kudu with his .270 and required a finishing shot on that one, too.

I have never known anyone using a .270 to make a one-shot kill on anything bigger than a springbok, which is smaller than a whitetail. I've killed many animals in North America and not a few in Africa using a .30-06 (with 180-grain bullets) and my 8x57. Of the African animals only two required more than one shot. One was a very large blue wildebeest—a notoriously tough species—and the other a medium sized warthog. Both required finishing because of my own poor bullet placement, for which I take responsibility, and no other reason. On the day I wounded the wildebeest I killed another one, instantly, with proper placement.

But all the animals shot with .270's that I've seen required second shots, despite near-perfect bullet placement. African game is so much more more tenacious of life and so much harder to kill than anything in North America, (grizzly bears included) that the .270 isn't up to the job.

O'CONNOR LIKED THE 7X57, SO DID W.D.M. BELL:

WHAT ABOUT THAT?

It will be asked why the 7x57, which fires a bullet of near-identical size to the .270, works so much better. It too has a good reputation on African game, despite the fact that its paper ballistics are somewhat inferior to the .270's and its momentum figure is no better. The answer to this riddle is simple: the 7x57 isn't a high-velocity round, and its bullet doesn't break up on impact. It remains intact and penetrates to the vitals. A heavy and tough bullet in the .270 would work just as well, but would negate the supposed "advantage" the .270 has in its high velocity and paper energies. Similarly, the 7mm Magnum, beloved of so many shooters and hunters in the western states, moves its bullets too fast. If one were to use heavily-constructed bullets in this caliber it would work...but then the "advantage" of the high velocity would be lost.

The argument is often made that the trajectory of high-velocity bullets is flatter and therefore they require less holdover at long range. This is true, and certainly relevant to western American or Canadian hunting conditions. But in Africa game is usually shot at much shorter ranges than it is in, say, Saskatchewan or Colorado. At 100 or even 200 yards the slower bullets are at no real disadvantage, and the much faster ones have an even greater tendency to disintegrate.

BLOWING THEM APART

Another drawback to high-velocity bullets universally condemned by African PH's is their tendency to damage meat. Americans hunt Africa for trophies, but it must be kept in mind that in Africa the landowner owns the game, and when an animal has been recovered its meat is sold for a profit. Local hunters usually won't pay the high fees visitors do, but they want "biltong" (jerky) and they do pay for their kills.

The messy damage caused by high-velocity bullets—especially on small animals like springbok—costs the biltong hunter money: he can't eat it. If a trophy is taken by a visitor that has significant meat damage it costs the farmer money because he can't sell that meat to a game merchant. I write for and do quite a bit of reading of African sporting journals. Articles on hunting rarely if ever mention calibers like the 7mm Magnum except in the context of a visiting American's safari and almost always there are negative comments on the meat damage that results when one is used, especially on chest shots.

IT WAS GOOD ENOUGH FOR GRANDPA...

It is a historical fact that the African continent was first colonized by people using muzzle-loading rifles firing large projectiles at low velocity; and later "conquered" by people using .303's, 7x57's, and 8x57's for the most part. The great 19th Century gun makers—Rigby, H&H, Mauser, Westley Richards, and many less-well-known companies—all had a steady trade supplying rifles to settlers and explorers in these and similar calibers. To some degree these were chosen due to the ready availability of military ammunition, but not entirely. The plain fact is that these calibers worked, and worked well in Africa. They still do.

OK, all you .270 lovers, the address for hate mail is on the first page of this site...or you can click here.

Probably for 90+% of Americans, whitetail deer are the biggest game they have ever encountered. Some will have hunted moose and some will have hunted elk. None of these compares to a blue wildebeest or an eland in any respect except size. The bison is probably the only North American mammal that remotely compares to large African game in terms of body size and bone structure, and few of us hunt those.

Probably for 90+% of Americans, whitetail deer are the biggest game they have ever encountered. Some will have hunted moose and some will have hunted elk. None of these compares to a blue wildebeest or an eland in any respect except size. The bison is probably the only North American mammal that remotely compares to large African game in terms of body size and bone structure, and few of us hunt those. else being equal, a heavy bullet has higher momentum than a lighter one. A bullet may have lots of energy but if it lacks momentum it cannot effectively translate that energy into adequate penetration.

else being equal, a heavy bullet has higher momentum than a lighter one. A bullet may have lots of energy but if it lacks momentum it cannot effectively translate that energy into adequate penetration.

on game will tell you about the remarkable size of the exit wounds it creates.)

on game will tell you about the remarkable size of the exit wounds it creates.)  understands his rifle and his quarry can do what needs to be done.

understands his rifle and his quarry can do what needs to be done.