THE FIRST ELEPHANT

Please note that this hunt was conducted in absolute compliance with the laws of Namibia and the United States. Everything described in this essay was completely legal. If you are offended by the idea of hunting elephants, please go to some other site.

I’m a city kid, born in a gritty working-class neighborhood of New York where the only “wildlife” I knew were sparrows, street pigeons and the grey squirrels who occasionally passed through our back yard. Nevertheless, as is true of all living humans, I’m descended from a long line of successful hunters. None of my immediate ancestors were hunters but my Pleistocene-era forebears certainly were—or I’d not be here. Their ancient genes re-surfaced in me early in life despite “isolation” in an urban environment.

When I was about 12 my father bought a weekend house that sat on 50+ acres of woods and contained an elderly single-barrel 20-gauge shotgun left behind by the previous owner. I promptly appropriated it, took the mandatory Hunter Education course, and bought my first hunting license (which I still have). Suitably equipped, I began the process of teaching myself to hunt, relying on what I read in books and Field & Stream magazine, which luckily—and inexplicably—was sold in the candy stores of my Bronx neighborhood. I had a lot to learn, and for years had to be content with small game. College and military service further limited my opportunities, and I was in my 30’s by the time I managed to take my first white-tailed deer. But by dint of persistence and by trial and error—mostly error—I did in time manage to figure out what I was doing and came to regard myself as a reasonably competent hunter of eastern North American game.

In addition to the treasure of an old gun, the house had a library of old books, among which were several Tarzan of the Apes novels. Now, a 12-year old boy is at the perfect age to read Burroughs’ dramatic tales. These romances engendered a thirst to hunt Africa specifically. I was unaware that Burroughs’ “Africa” was completely imaginary but that didn’t matter.

In addition to the treasure of an old gun, the house had a library of old books, among which were several Tarzan of the Apes novels. Now, a 12-year old boy is at the perfect age to read Burroughs’ dramatic tales. These romances engendered a thirst to hunt Africa specifically. I was unaware that Burroughs’ “Africa” was completely imaginary but that didn’t matter.

African hunting became something of an obsession, but it was not until my late 50’s that my income would support any form of it. I managed to tack a 5-day self-catered safari in South Africa onto a month-long vacation I’d promised my wife. That first African hunt was an amazing experience that reinforced my belief that Africa was the place I needed to hunt, as often as possible. Even that modest “entry-level” safari completely spoiled me for hunting anywhere but Africa. I had to go back.

Most new safari-goers start with plains game, as I did. When I decided to do it again, I chose to go to Namibia, which is pretty much a plains-game-hunter’s Paradise, offering numerous species at reasonable prices, plus outstanding infrastructure. A very good package offer from a company named CEC Safaris, whose owner, Cornie Coetzee, came to me with high recommendations, resulted in a 10-day hunt in the central part of the country that garnered me several Gold Medal animals, as well as a love for Namibia’s huge spaces and abundant free-roaming animals. I was even more completely hooked.

Namibia recognizes that big game hunters are a major source of hard currencies, and makes them very welcome. Entry with firearms is a simple process; after a few formalities at the airport that take only minutes, you’re on your way. The government is also very ecologically savvy. They understand and encourage the “sustainable use” model for game management, whose effectiveness is attested to by the enormous numbers of free-roaming animals you see everywhere.

Hunting plains game, as exciting as I had found it, just set the stage for the next challenge: I wanted—no, I needed—an elephant. I contacted Cornie again and after some discussion we settled on a price and dates. I ordered a new rifle and began my preparation for the hunt of a lifetime in earnest. I would be in the easternmost part of the Caprivi Strip, the “tail” of land in northeastern Namibia, between Angola and Zambia on the north, and Botswana on the south.

Hunting plains game, as exciting as I had found it, just set the stage for the next challenge: I wanted—no, I needed—an elephant. I contacted Cornie again and after some discussion we settled on a price and dates. I ordered a new rifle and began my preparation for the hunt of a lifetime in earnest. I would be in the easternmost part of the Caprivi Strip, the “tail” of land in northeastern Namibia, between Angola and Zambia on the north, and Botswana on the south.

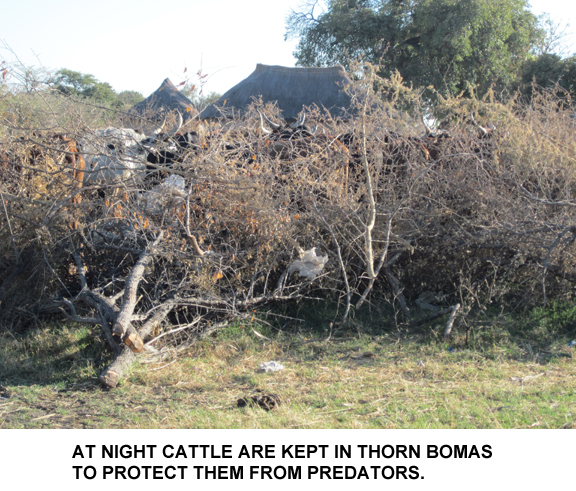

The Caprivi is undoubtedly The Real Africa. Central Namibia consists of enormous privately-owned cattle and game ranches, but the Caprivi is all National Park and tribal lands, whose inhabitants for the most part live lives not very different than those their ancestors did.

The Caprivi is undoubtedly The Real Africa. Central Namibia consists of enormous privately-owned cattle and game ranches, but the Caprivi is all National Park and tribal lands, whose inhabitants for the most part live lives not very different than those their ancestors did.  Villages with populations of a few dozen to a few hundred are scattered throughout, wherever a reliable water source is available. The houses and other buildings are made of reed bundles tied together—a traditional construction method in this part of the world—and primary occupations are cattle herding or fishing. It’s a place where in some respects Time has stood still, whose inhabitants generally are content with the quiet, peaceful, and changeless existence they lead.

The Caprivi Strip is also an incomparable venue for dangerous game hunting.

Villages with populations of a few dozen to a few hundred are scattered throughout, wherever a reliable water source is available. The houses and other buildings are made of reed bundles tied together—a traditional construction method in this part of the world—and primary occupations are cattle herding or fishing. It’s a place where in some respects Time has stood still, whose inhabitants generally are content with the quiet, peaceful, and changeless existence they lead.

The Caprivi Strip is also an incomparable venue for dangerous game hunting.

In Namibia, unlike South Africa, high game-proof fences are very much the exception to the rule. Ninety-five percent of the land, even on enormous private ranches, is unfenced. Only where non-indigenous species (such as black wildebeest) have been brought in will you find a high-fenced farm, because Namibia law requires this.

In Namibia, unlike South Africa, high game-proof fences are very much the exception to the rule. Ninety-five percent of the land, even on enormous private ranches, is unfenced. Only where non-indigenous species (such as black wildebeest) have been brought in will you find a high-fenced farm, because Namibia law requires this.

A typical Namibian ranch is about 10,000 hectares (38+ square miles), roughly half again as large as Manhattan Island. Many are much larger: a ranch the size of the District of Columbia isn't unusual. The stupendous cost of every kilometer of high fencing makes it impractical on properties of such size, so native game species (who simply ignore cattle fences) roam freely even in the central part of the country. The huntable regions of the Caprivi Strip are completely open and unrestricted, with truly wild animals, including elephants, moving where they will. There aren't many places in the world where you will see "Elephant Crossing" signs on the highways, but the Caprivi is one of them.

Tribal areas in the Caprivi are administratively subdivided into “conservancies,” whose authority includes local game management. Elephants legally belong to the conservancy in which they’re located. Every season each conservancy—in consultation with the Ministry of Environment, local tribal Chiefs, the hunting industry, and conservation groups—sets a quota for elephants to be taken. The quota elephants are sold to safari companies (who pay in advance) who in turn retail them to foreign hunters.

Tribal areas in the Caprivi are administratively subdivided into “conservancies,” whose authority includes local game management. Elephants legally belong to the conservancy in which they’re located. Every season each conservancy—in consultation with the Ministry of Environment, local tribal Chiefs, the hunting industry, and conservation groups—sets a quota for elephants to be taken. The quota elephants are sold to safari companies (who pay in advance) who in turn retail them to foreign hunters.

The goals of this system are to maintain the overall herd size at a level consistent with the carrying capacity of the land by removing surplus individuals; and to generate income for the conservancy’s operations. A conservancy official (i.e., a game ranger) goes along on the hunt and the subsequent recovery operation to ensure the rules are followed. Decades of practical experience and sound wildlife management science go into setting of each year's quotas, and this proven model—based on the needs of the entire game population rather than those of individual animals—works exceptionally well.

There are two classes of quota elephants. "Trophy" elephant have very large tusks and are very, very expensive for that reason; and because they’re “exportable” (that is, the government allows the ivory to be taken to the hunter’s home country assuming his local laws permit it). “Non-exportable” animals, what are referred to as "own use" animals, are those of lesser quality—like the one I hunted—and they will cost the hunter far less. This doesn't mean they're small, however. The elephant I killed was a very good sized one, whose tusks were very respectable. These "own use" animals are the ones that should be cropped out of the population to maintain a proper balance in the local ecosystem.

The sustainable-use model also directly serves the interests of the local inhabitants. Meat from kills can’t be exported, so the meat, viscera, and bones are allocated by the conservancy to one of the local villages. After a kill the game officer calls in the GPS coordinates. Whichever village has been designated to receive the meat sends out a group of men to butcher the carcass. Dried and preserved, game meat provides a principal source of protein: a good-sized elephant represents a year’s worth of meat for 300 or more people. Not only the meat, but everything else gets used: the hide is made into expensive leather goods, the bones and viscera get eaten, too. The only thing left behind is a big blood spot. Everyone in the village gets a few dollars from the fee the hunter pays. The ivory is impounded and stored by the Namibian government. Everyone wins, except, of course, the elephant.

The bush camp from which we operated was in Sobbe, run by Karl Stumpfe of Ndumo Safaris. Karl had the concession rights to the area we hunted and my PH, Cornie Coetzee of Cornie Coetzee Safaris, had an agreement with him to bring dangerous-game clients there.

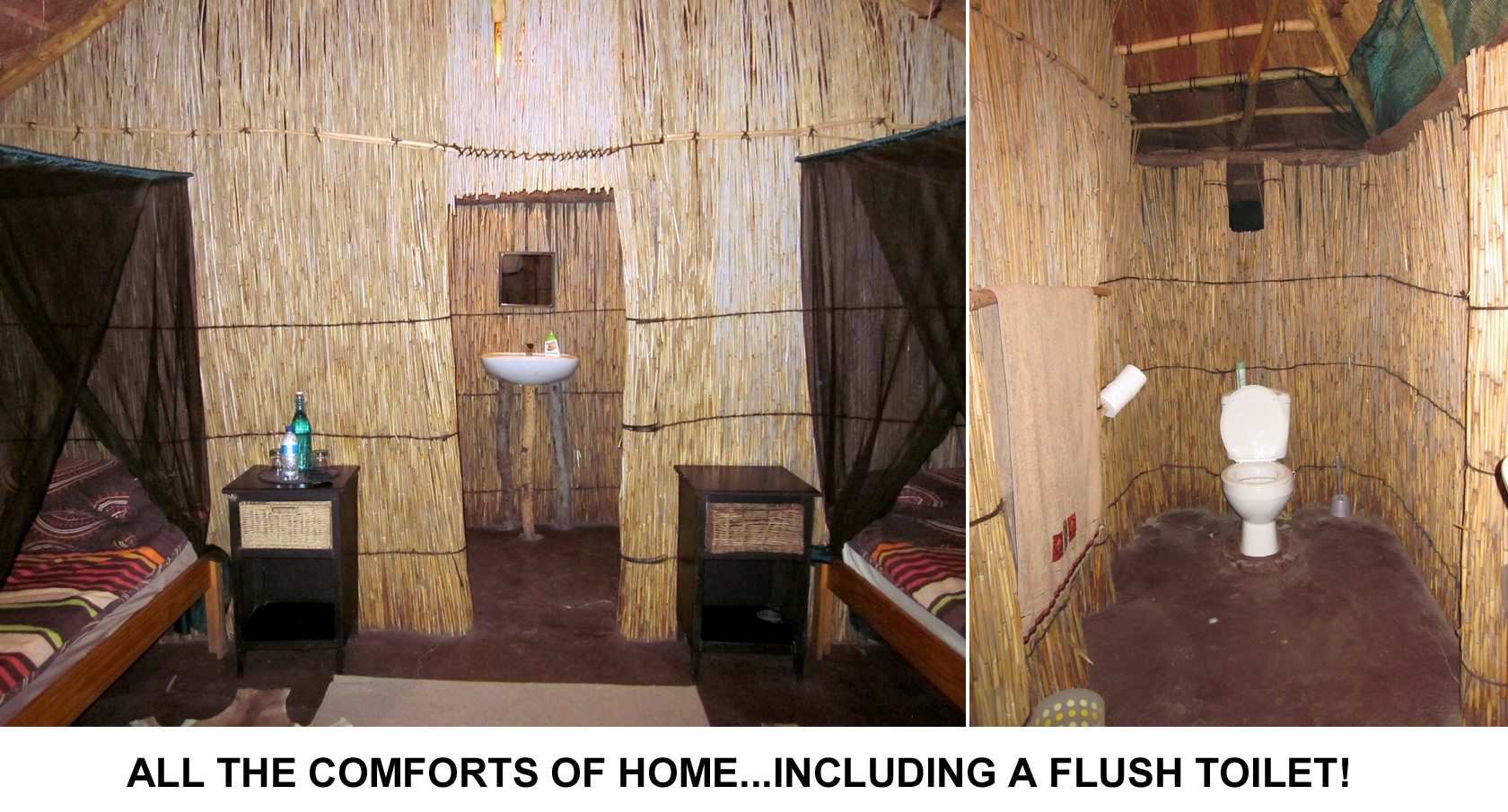

There's a saying that "The worst camp in Africa is better than the best one in America," and based on my experience of hunting camps on both continents, this is true. Karl's camp is certainly rustic, but by no means as primitive as, say, a spike camp on Alaska's North Slope. The huts are made of reeds but they have concrete floors, hot and cold running water (brought in by truck from 10 kilometers away and pumped into a storage tank), and flush toilets. Meals are prepared by a staff cook and are served in a large open dining hut.

Maids keep the huts orderly and clean, there is daily laundry service, and every night hunters and hosts sit around the campfire, have a few drinks, and shoot the breeze. In a bush camp like this you lack the ambiance of unwashed men and stale beer typical of a North American deer camp; and the unmatchable experiences—common on Alaskan wilderness hunts—of wearing the same underwear for a week and eating MRE's are missing; but I can live with that.

The camp was two hours’ drive from the actual hunting area, which meant very early wake-up times. We were hunting on flatlands along the Zambezi River, an area dotted with small native villages. The flats are flooded in Summer but in the winter things dry out enough to drive a 4WD Land Cruiser around.

There are no roads to speak of, merely tracks between the villages, so we were bush-bashing most of the time. Soft spots remained under the grass, and the Land Cruiser bogged down from time to time, but with some effort it was extricated and we went on our way. It was a good thing we were able to get it unstuck: the last thing we wanted was to be out on the flats after dark, because people who do that find out that they are not, in fact, at the top of the food chain. Yes, there are lions.

It took considerable time to find fresh elephant tracks, but toward the end of the day we spotted a trail and began to follow it. Fairly soon thereafter we  saw the herd that made the tracks perhaps 1000 yards away. We slowly moved downwind, dismounted, and began a careful foot stalk upwind, starting 400 yards from the herd. Constant checking of the wind with an ash bag allowed us to approach with the wind always in our faces, and we moved as stealthily as we were able. Elephants don’t see very well but they have phenomenal noses and hearing.

saw the herd that made the tracks perhaps 1000 yards away. We slowly moved downwind, dismounted, and began a careful foot stalk upwind, starting 400 yards from the herd. Constant checking of the wind with an ash bag allowed us to approach with the wind always in our faces, and we moved as stealthily as we were able. Elephants don’t see very well but they have phenomenal noses and hearing.

For all their size elephants are fairly skittish and will run from perceived danger. We didn't want to alarm them, not because of the chance of a charge, but because we didn't want to frighten them away. Once we began the stalking phase, I loaded my rifle and got ready. Elephant are always hunted at very close range: my rifle had been sighted in at 50 yards, but our intention was to get within 30 yards, closer if possible. There were about 50 animals in the herd. As we approached, they moved into and started feeding in a scrubby wooded area, still upwind of us and still unaware of our presence. Everything was going very well: the beasts were feeding contentedly among the scrub, and we were creeping along pretty much without a sound.

Then I saw him: THE elephant, the one I’d waited more than half a century to encounter. He was a big bull, much larger than the two askaris flanking him or the cows composing most of the herd.

"X" marks the spot. Scroll over this image to see exactly where the bull was standing

when I fired.

From the moment I laid eyes on that bull, I saw nothing else: I experienced total “target fixation,” but I remained very calm throughout the encounter. Looking back on it, this still is a bit surprising to me. I’ve never been prone to “buck fever,” but I had anticipated that adrenalin would be flowing and my heart racing under these conditions: but it didn’t happen. At the moment I saw the bull I was perfectly aware of what I was going to do and knew exactly how I was going to do it.

The wind shifted a trifle, and the herd began to sense that something wasn’t quite right. Perhaps they had a whiff of us, but were undecided as to whether or not we represented a real threat. Nevertheless they were uneasy enough that they started to move, slowly, from our left to our right, perhaps 40 yards away. It was obvious we weren’t going to get any closer, and that if they kept moving far enough they’d get downwind, and off they’d go.

I was still intently watching my bull as he moved through the scrub towards a more open space, where I knew I’d get a good look at his right side. Sure enough, as he stepped forward into the little clearing my PH set up the shooting sticks: I very deliberately set the red dot of my sight on his right side: it was time.

I fired, and half a second later, so did Cornie; Karl fired a third shot half a second after that. The noise sent the herd into a panic, running in the same direction they’d been walking a moment before. To be honest, I didn’t see them go, I was so fixed on my bull. Less than 30 seconds after I fired I heard the shout “He’s down!” And so he was, within 100 yards of the spot where he was hit. We approached very cautiously, I fired an “insurance” bullet into the back of his neck where it joined the head, and that was that.

I didn’t see them go, I was so fixed on my bull. Less than 30 seconds after I fired I heard the shout “He’s down!” And so he was, within 100 yards of the spot where he was hit. We approached very cautiously, I fired an “insurance” bullet into the back of his neck where it joined the head, and that was that.

The whole affair still has a dream-like “time compression” quality to it. There’s an image seared into my visual cortex of the dot on the bull’s side, and I remember hearing my shot go off, but I felt no recoil at all. That half-minute between the moment I settled in for the shot and the cry of “He’s down!” was over so quickly it hardly seems that it could have really happened, looked at in the cold light of memory.

But there he lay, still and lifeless, the very embodiment of a dream that had occupied most of my life. He was very old, perhaps 40-45 years, quite large—possibly 6 tons—but well past his prime. He would likely never have sired another calf. One tusk was broken, the other intact: the estimate was that the intact tusk weighed about 40 pounds. He was a perfect choice for culling.

I was using an E.R. Shaw rifle I'd ordered two years before, specifically for this hunt. It is in .416 Remington caliber, a real bruiser of a cartridge: when you pull the trigger you know something has happened! The .416 Remington is used by many PH's as a versatile "all around" caliber. My ammunition was Hornday's "DGS" solid-bullet 400 grain loads. Hornady makes a soft-point version with identical ballistics, but for dangerous game, heavy solids are necessary for their very deep penetration. The Hornady bullet performed perfectly, penetrating several feet of hide, muscle, and bone without deformation, in a perfectly straight line. One bullet was recovered intact when the head was skinned out: it was from the "insurance" shot I fired into it. It was marked with the rifling but otherwise undamaged.

Man is the Ultimate Predator, who dares to hunt animals vastly larger and more powerful than he is.

Man is the Ultimate Predator, who dares to hunt animals vastly larger and more powerful than he is.  It has always been so. We were, after all, hunters before we were humans, and our earliest cultural and artistic artifacts are cave paintings of hunting scenes. Hunting is so inextricably bound up in the origins of humanity that—however rational a man may be—if he is a hunter, deep within him there is a solid kernel of primitive superstition, a remnant of ancient beliefs in magic and the control of our fates by forces we don’t understand.

It has always been so. We were, after all, hunters before we were humans, and our earliest cultural and artistic artifacts are cave paintings of hunting scenes. Hunting is so inextricably bound up in the origins of humanity that—however rational a man may be—if he is a hunter, deep within him there is a solid kernel of primitive superstition, a remnant of ancient beliefs in magic and the control of our fates by forces we don’t understand.

So it’s inevitable for me to wonder just how my life path and the bull’s came to converge. He would have been born just about the time my desire to hunt Africa was being fired by Burroughs’ stories. Was our first and last meeting entirely by chance? Or is there, perhaps, really a providence in such things, some irresistible force beyond our understanding, that guided both of us to that remote spot at that exact time? In my hunting life I’ve had many emotional experiences, but this first elephant was a life-changing event. Seeing that great, still beast upon the ground brought home in a way none of my other kills have the truth that all life is one, and but for technology and a good bit of luck, things might well have gone the other way.

Would I do it again? Of course, assuming my health and finances permit: I am, above all else, a hunter, and a hunter must hunt. But no future hunt, even another elephant, can have the same meaning and mystical significance for me that this one did. I’m at an age where the end of my hunting experiences is a visible reality on my life horizon. That time is not yet, but some day, I too will lie still and cold. When that happens, perhaps I will meet my bull again.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |