CONVERSION CYLINDERS FOR BLACK POWDER REVOLVERS

The Centennial Commemorative of the American Civil War in 1960-65 gave rise to a new product for shooters: close replicas of the percussion-fired weapons used in that conflict, both rifles and handguns. Replicas were far less expensive than original guns and as a bonus they were much stronger, thanks to better materials and modern engineering practices. They quickly became popular items. Then the “Cowboy Action Shooting” (CAS) game of 20-30 years later made reproduction revolvers even more popular, and along the way created a new niche product: replacement cylinders to convert them to safe use with fixed ammunition loaded with smokeless powder.

The Centennial Commemorative of the American Civil War in 1960-65 gave rise to a new product for shooters: close replicas of the percussion-fired weapons used in that conflict, both rifles and handguns. Replicas were far less expensive than original guns and as a bonus they were much stronger, thanks to better materials and modern engineering practices. They quickly became popular items. Then the “Cowboy Action Shooting” (CAS) game of 20-30 years later made reproduction revolvers even more popular, and along the way created a new niche product: replacement cylinders to convert them to safe use with fixed ammunition loaded with smokeless powder.

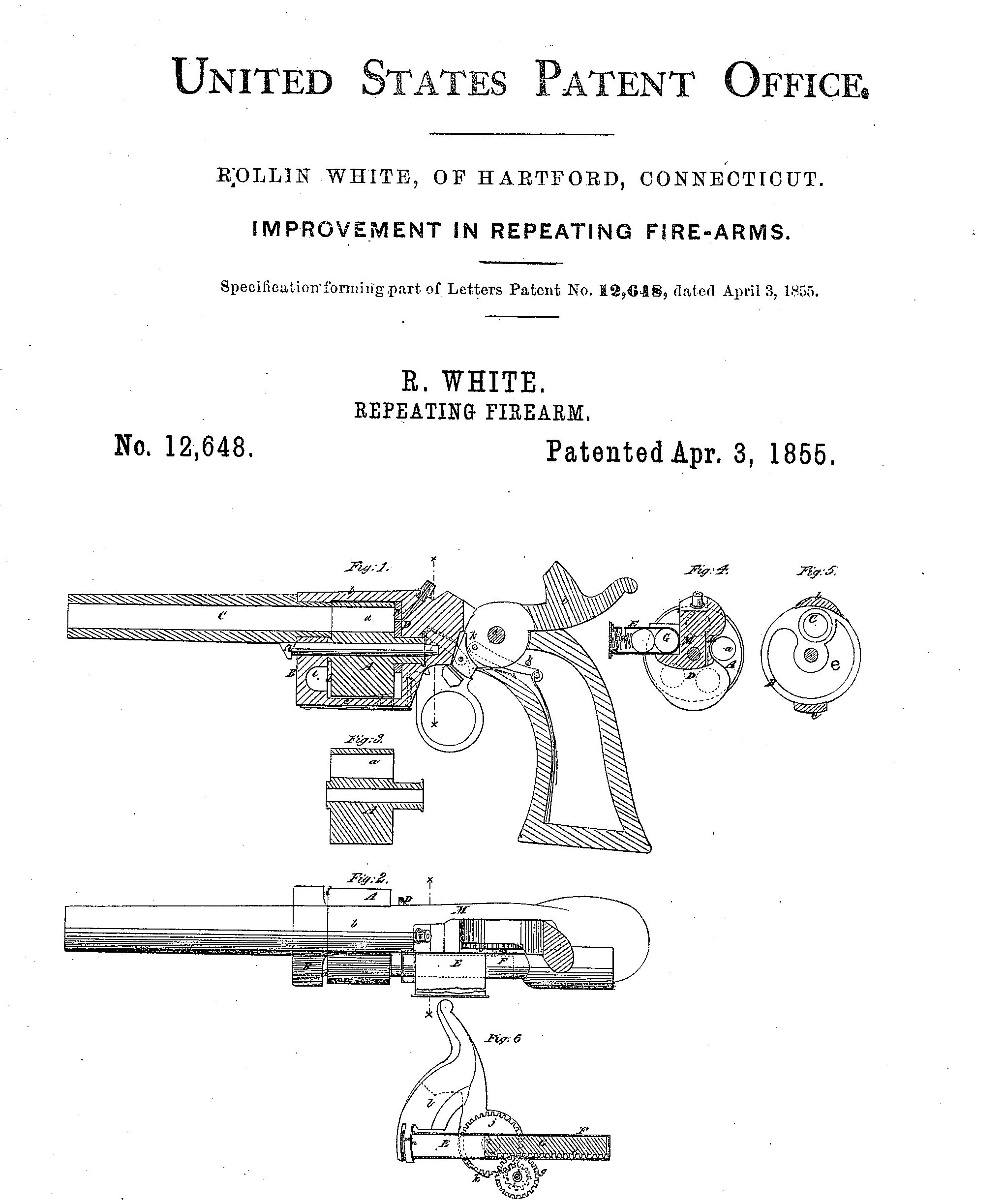

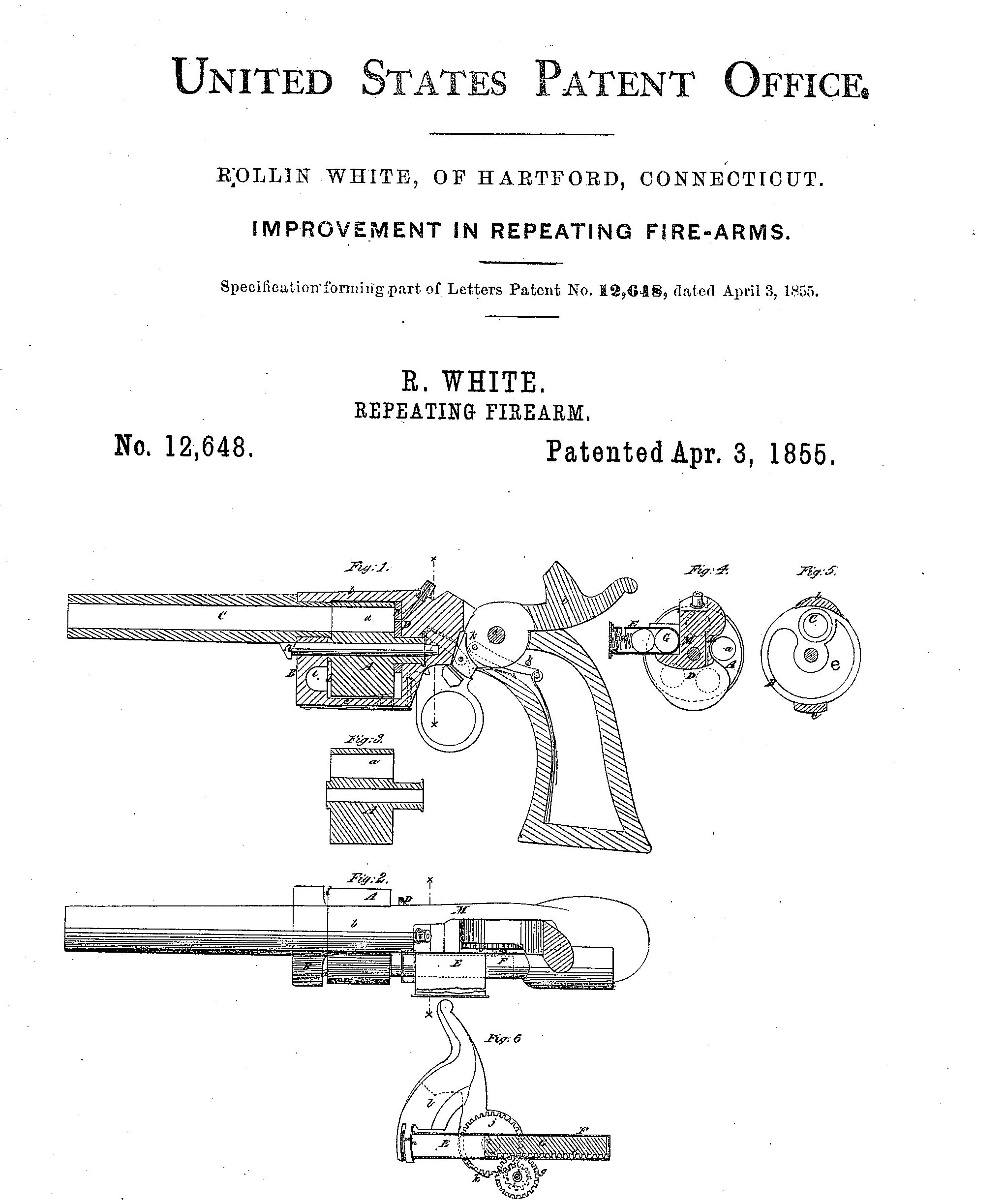

Conversion cylinders aren’t new. Rollin White’s Patent #12648 of 1855 gave Smith & Wesson a monopoly on revolver cylinders bored through to insert cartridges from the rear. During the life of the patent, S&W’s competitors—chiefly Colt—vainly tried to come up with an equally convenient way to convert percussion guns to fixed ammunition without infringing on S&W’s patents. They failed, but S&W lost their monopoly when the patent expired in 1872; anyone could then use the technology and everyone did as soon as they could get tooled up.

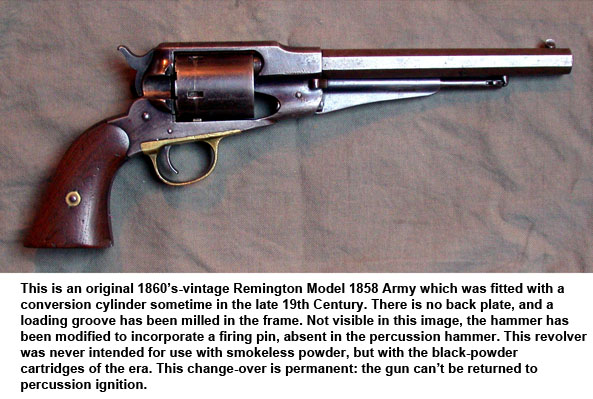

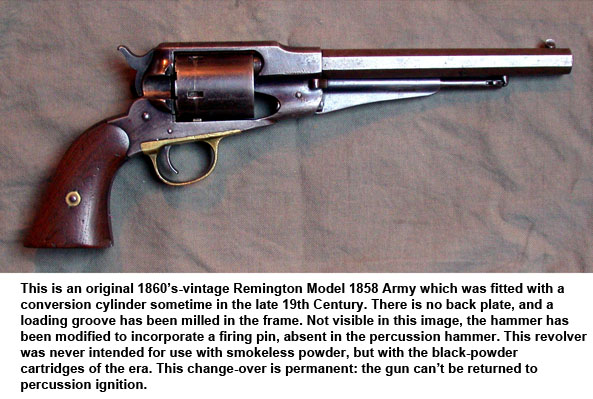

A high-quality revolver by Colt or Remington was a significant financial investment, especially for the ex-soldiers and new settlers who flooded the newly opened lands of the American West after the War was over and the Transcontinental Railroad completed. Understandably reluctant to get rid of perfectly serviceable (if obsolete) firearms, they were ready-made buyers for an economical and effective way to convert their existing revolvers to more convenient and reliable fixed ammunition. A replacement cylinder was a pretty obvious solution: properly designed it had the additional advantage that it wouldn’t preclude using the percussion cylinder if needed. The conversion cylinders developed in the late 19th Century were more or less identical to the ones currently being made today. Typically a conversion cylinder is a two-piece affair: the cylinder proper and a removable back plate. One manufacturer incorporates a loading gate and a single firing pin into the back plate. A more common type has a solid back plate housing a firing pin for each chamber.

To load the gun, the original percussion cylinder has to be removed (an easy matter, especially with a Remington). With the loading gate type the process is exactly the same as loading a Colt Single Action Army: the gate is opened and cartridges inserted into each chamber, rotating the cylinder to bring each one in line with the gate, which is then shut. In the type with no loading gate, the back plate is removed, cartridges are inserted into all the chambers, the two pieces are re-assembled and the entire assembly put into place. Thanks to CNC machining usually no gunsmithing is needed to effect the transition: the cylinder just drops into place.

The most popular calibers for percussion revolvers are .36 and .44. However, a “.36” caliber percussion revolver isn’t really a .36 at all. Conversion cylinders for .36-caliber revolvers will use either .38 Long Colt or .38 Special. This is possible because a “.38” isn’t really a .38 in the first place. The “.38” of either the Special or Long Colt is purely notional: those two calibers really use bullets of 0.358” to 0.360” diameter, and shooting them in a .36 caliber bore isn’t in any way dangerous. The .44-caliber revolvers have a groove diameter of 0.450” and are adapted to use round balls 0.451” in diameter. They will safely handle the .45 Long Colt caliber, whose bullets run 0.454” in diameter, even so.

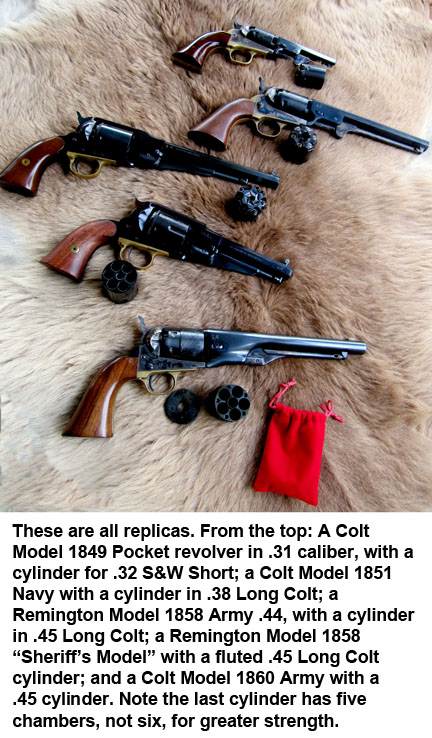

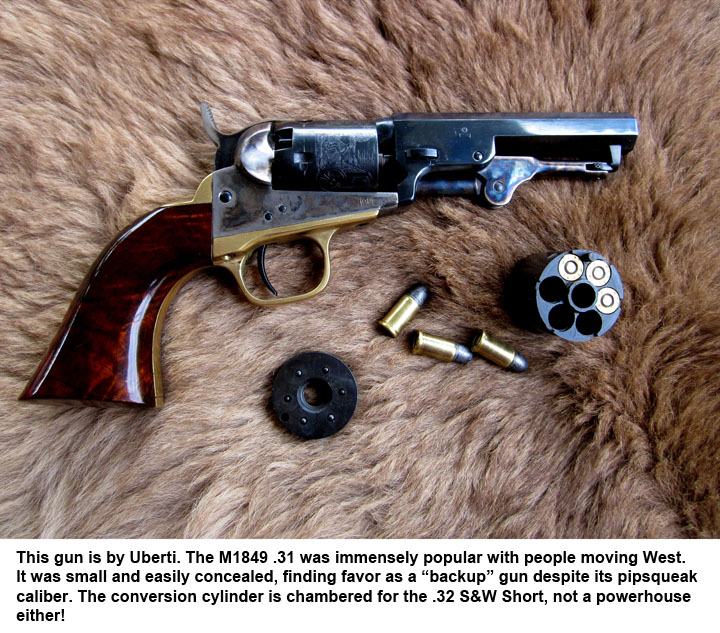

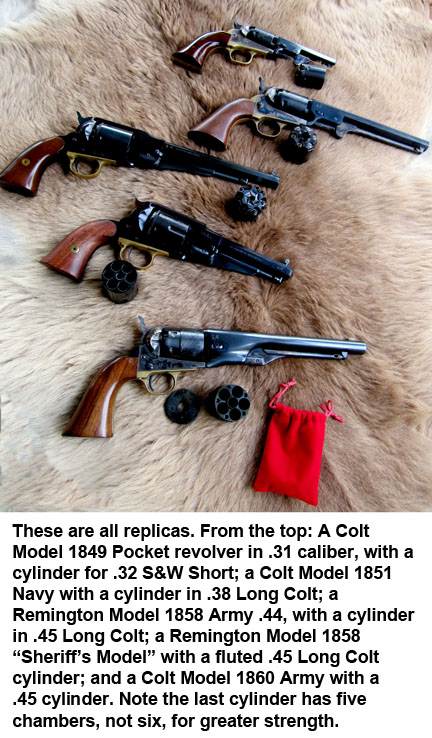

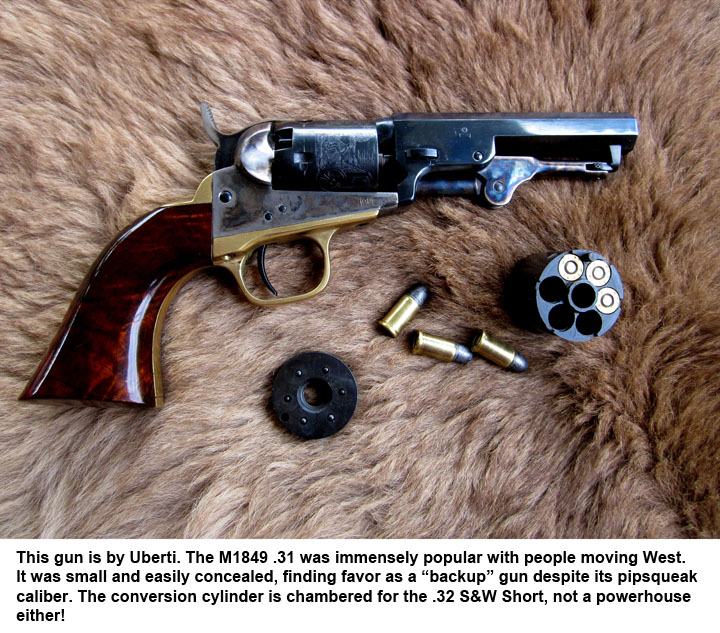

The popularity of the large-bore cylinders inevitably led to some being produced in smaller calibers. The smallest I’m aware of is one for the Colt Model 1849 Pocket revolver. This diminutive and appealing gun was one of Colt’s hot sellers, especially among prospectors headed to the California Gold Rush in 1848-49. While the M1849 is nominally a “.31” caliber the conversion cylinder fires the .32 S&W Short round, which has a bullet diameter of 0.312” that works quite nicely.

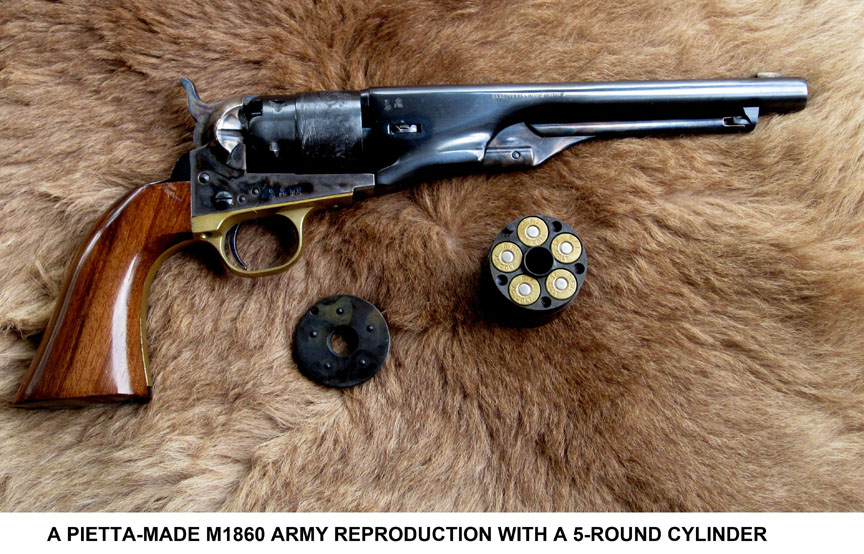

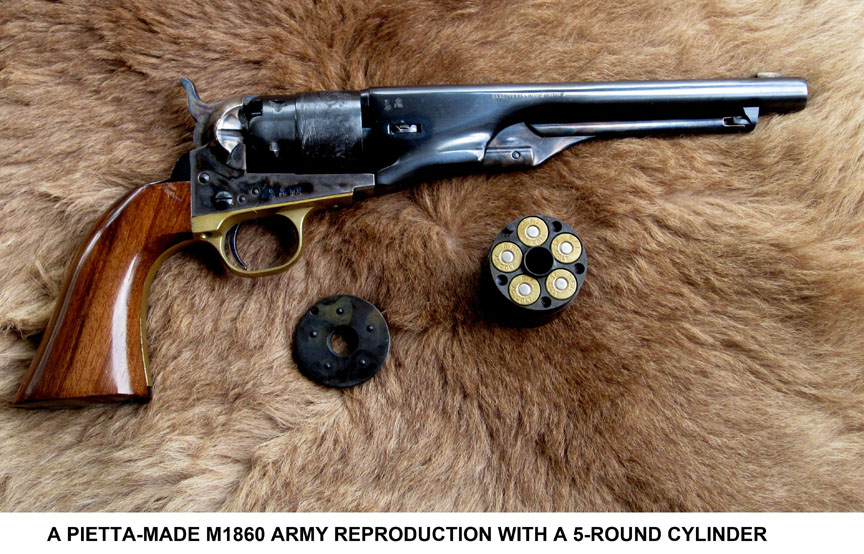

There are some issues to be considered when using these cylinders. It has to be borne in mind that even though present-day replicas are better than anything the old-time manufacturers could have produced, thanks to their metallurgy and machining, they're nevertheless inherently weaker than modern double action revolvers designed for heavy loads. You can’t safely use “Plus-P” type ammunition without real risk. The cylinder manufacturers uniformly specify that their products are to be used only with loads at the “Cowboy Action” level. They’ll handle normal pressure loads nicely but “hot-rodding” things past the specified limits is not a good idea. In particular Colt’s open top design, dependent on a wedge that joins the barrel to the frame, is much weaker than the solid-frame Remington type. I have both a Colt and a Remington, both nominally .36’s; the Remington cylinder is chambered for .38 Special; the weaker Colt for the lower-powered .38 Long Colt round. My 1860 Army replica in .44 has a cylinder that chambers only five rounds, not six. This gives somewhat greater strength, as the cylinder notches are between chambers, not over them. On the whole, it’s best to use factory ammunition, although reloads with proper charges are safe and much cheaper.

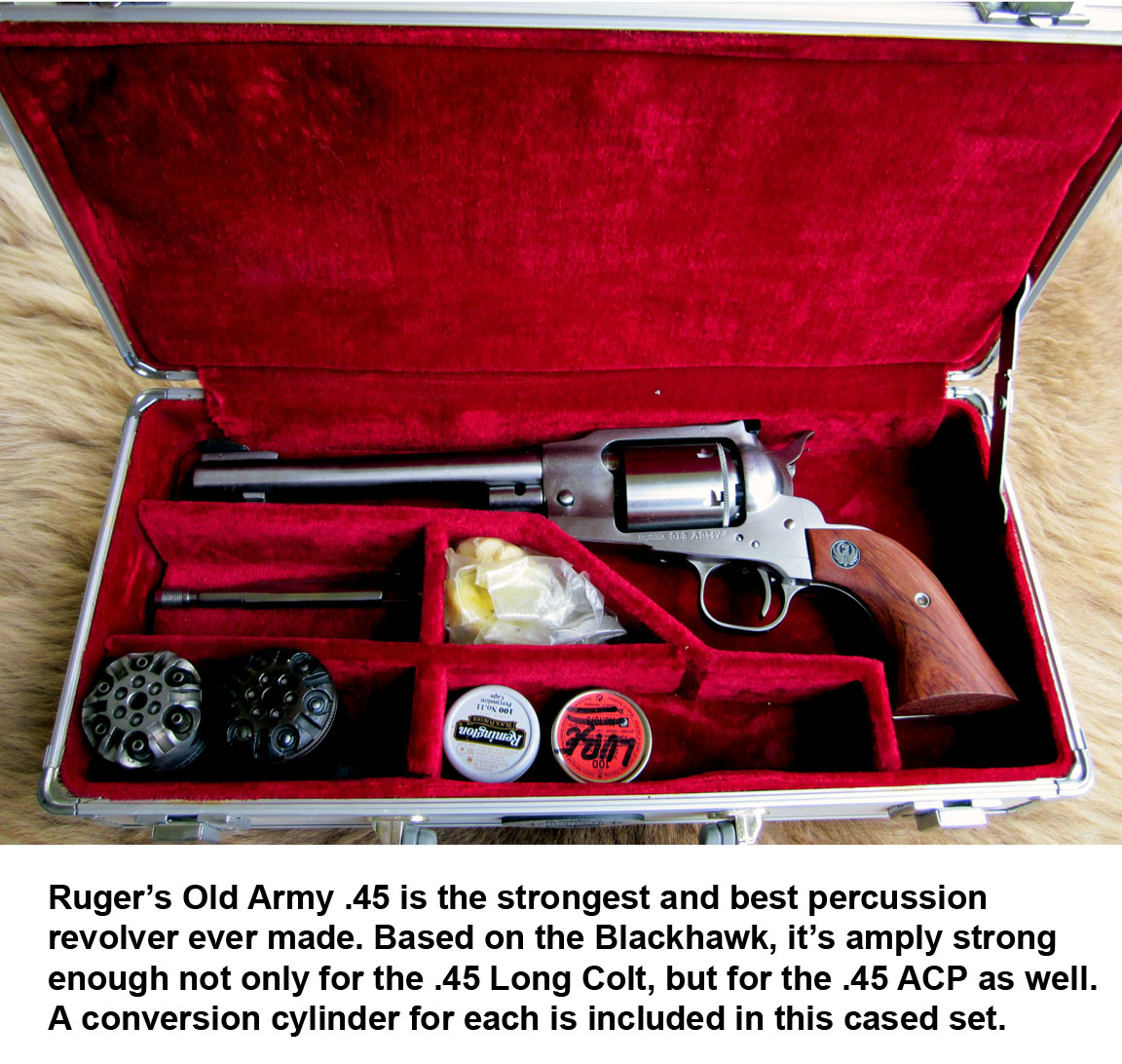

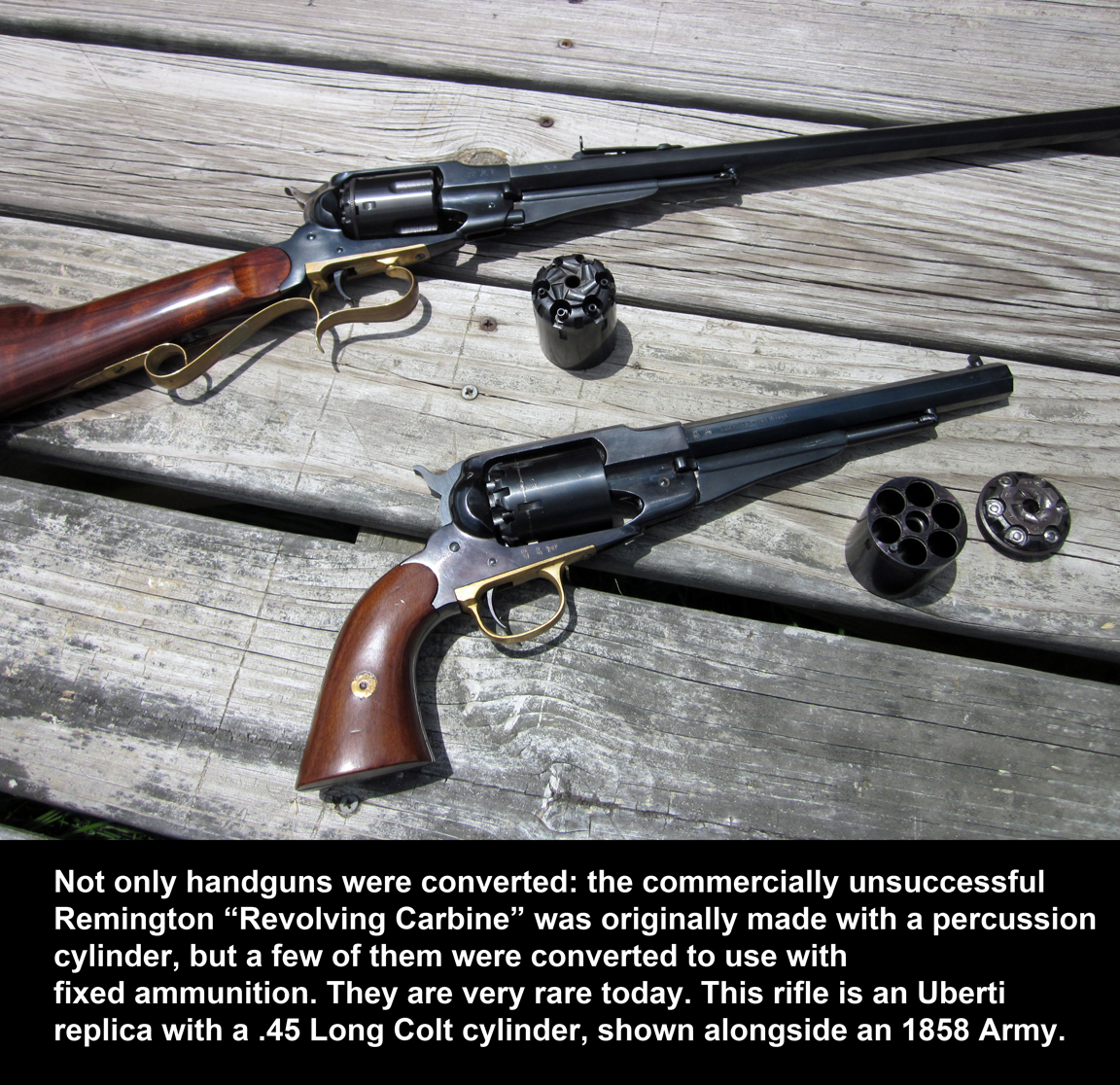

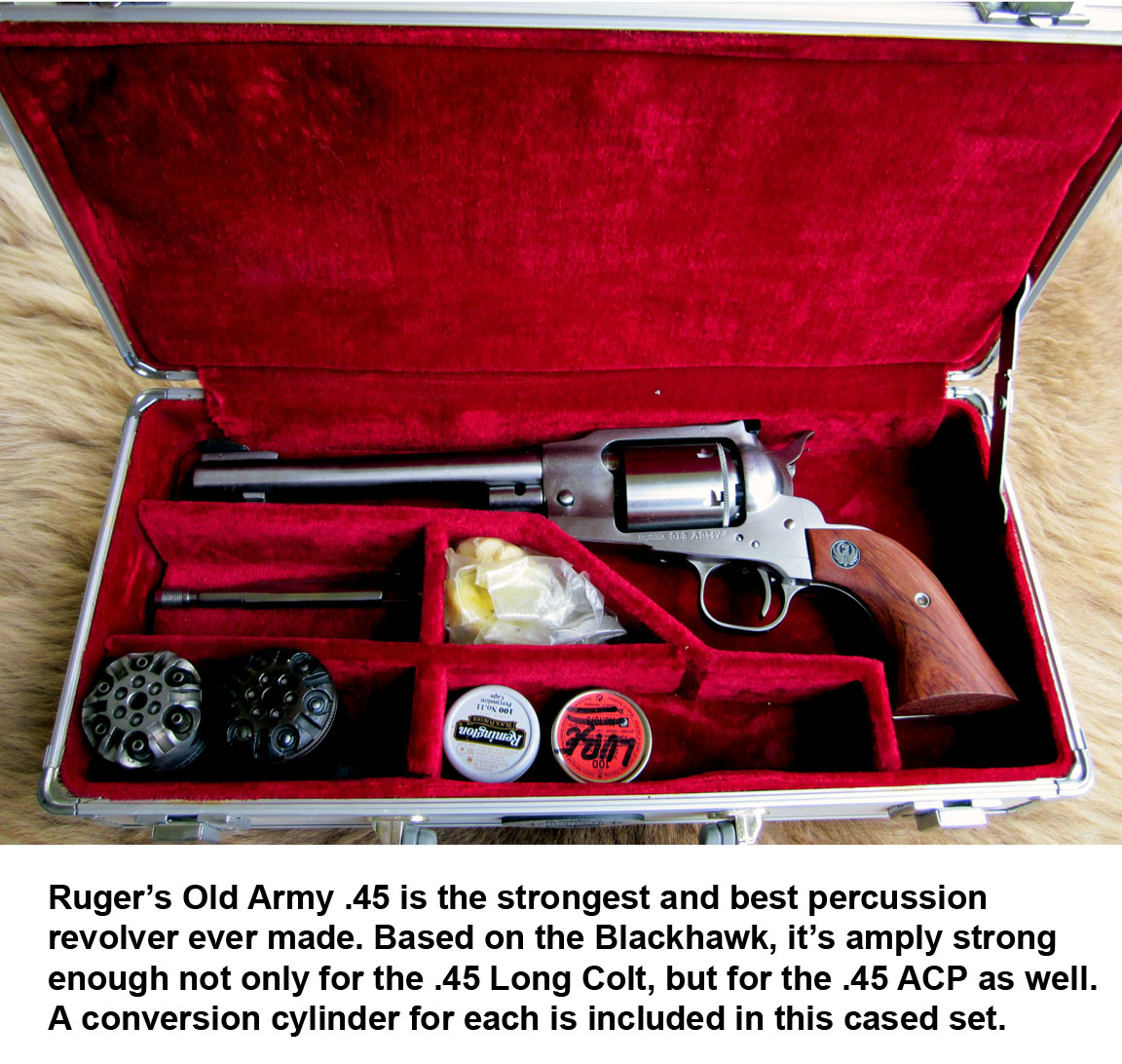

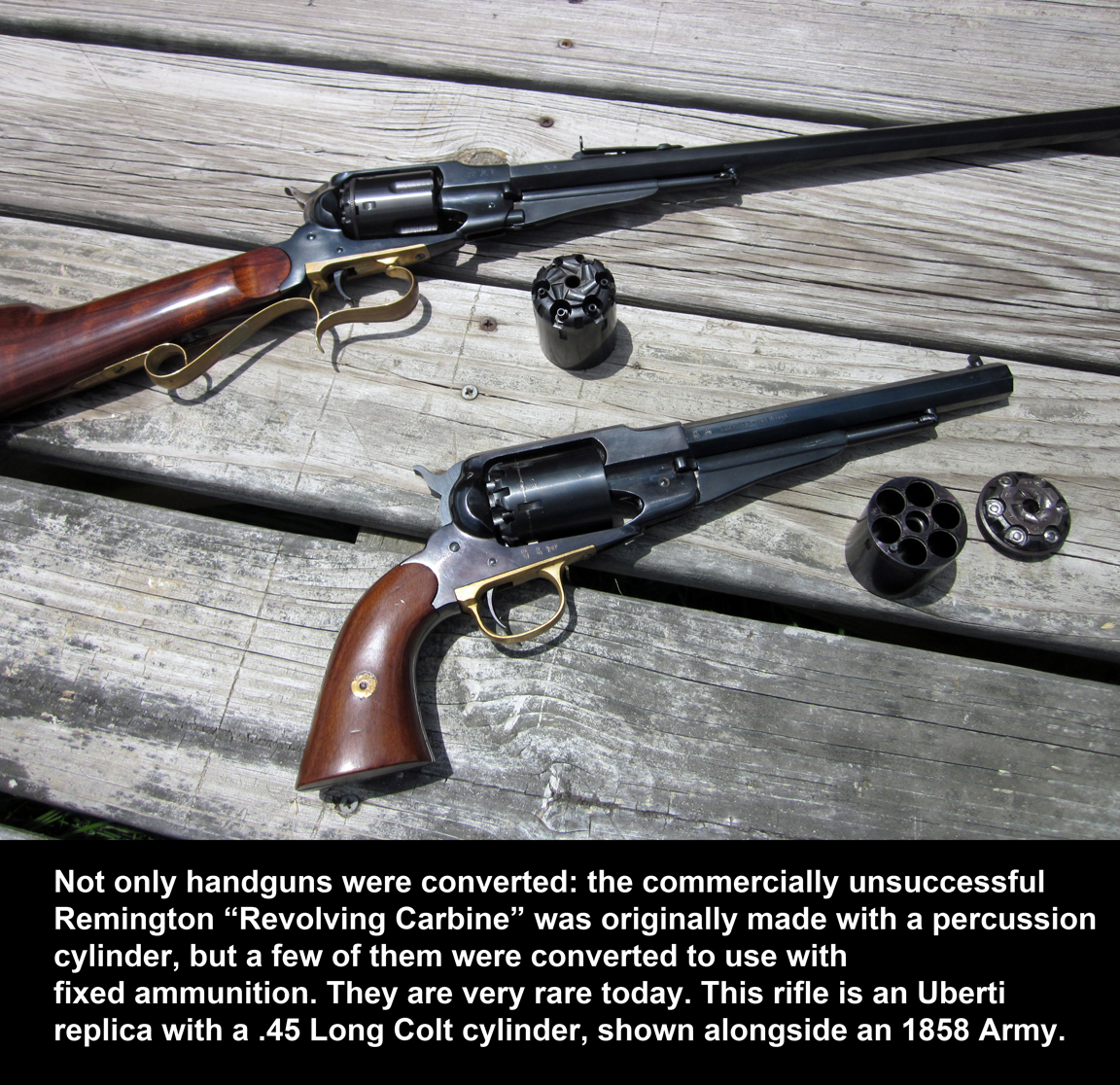

Cylinders aren’t made for all replica revolvers. They’re made for the enormously popular Remington Model 1858 Army and the Colt 1860 Army (both .44’s). The Colt 1851 Navy .36 can be fitted with one, as well. One exceptionally sturdy modern percussion revolver, far stronger than anything the old-timers could have imagined or produced, is the Ruger Old Army, a gun now—alas—no longer made. This beautiful gun was sold as a .45 caliber, not a .44 as are the older designs. Ruger rifled it with the same machinery used in their centerfire handguns, so its groove diameter is 0.452” not 0.450”. The Old Army can be fitted with a cylinder for .45 Long Colt, and also one for the .45 ACP. One manufacturer markets a .45 ACP cylinder for the Remington Model 1858 Army but I have not tried one of these in mine.

One gun that I wish could be fitted with a conversion cylinder is the graceful and beautiful Colt M1862 “Police” .36. Colt’s last percussion design, it is an elegant handgun that’s compact, lightweight, and reasonably powerful for its day, even with black powder. But the fluted cylinder is too short and has too small a diameter; no available centerfire caliber can be fitted to it. I’ve heard rumors that someone is planning to make a conversion to use the .380 ACP, but I’ll believe it when I see it. If I do see it, I’ll buy it!

A real no-no is using conversion cylinders in brass framed revolvers. Brass is substantially softer and more ductile than steel. Even heavy loads of black powder in percussion cylinders, over time, will cause the frame to stretch and the gun to “shoot loose.” Fixed ammunition, even “Cowboy Action” loads, do operate at somewhat higher pressures than anything using black powder; plus they shoot heavier bullets than the round balls typically used in percussion-ignition shooting. When made of pure lead, a .451” diameter ball weighs 137 grains; the lead round nose bullet used in the .45 Long Colt weighs 250 grains. The .375” ball used in a .36 revolver weighs 79 grains; the standard load for a .38 Special fires a 158-grain bullet. These differences really stress a brass frame. Steel frame guns are much stronger and will easily tolerate being used with “regular” bullets, but even steel has its limits.

Performance of fixed ammunition in conversion cylinders is much the same as it is with the black powder cylinder in place, making allowances for greater bullet weights. “Cowboy Action” loads are intended to duplicate percussion ballistics. In my experience factory .45 Long Colt fired from the 7-1/2” barrels of the Remington M1858 or the Colt M1860 is pretty much exactly what you would expect, about 850 FPS with the 250-grain bullet. Similarly the .38 Special and Long Colt ammunition give the same performance as they would in a double action revolver in either caliber. Some adjustments may be needed in sight picture or hold when switching to fixed ammunition, but most percussion revolvers are quirky in that respect anyway.

Conversion cylinders aren’t cheap. They’re manufactured to very close tolerances and regardless of maker all of them are exceptionally well made and finely finished. A conversion cylinder can easily cost as much as the gun to which it’s fitted, but they offer those who shoot old-time single-action revolvers for fun a great deal of convenience and flexibility. With standard-velocity ball ammunition, the big single-action guns like the Remington 1858 or the Colt 1860 aren’t the least bit uncomfortable to shoot; shooting .38 Special in a Model 1863 “Belt Model” Remington or the .38 Long Colt in an 1851 Navy is sheer fun. Shotshells are commercially available in both .38 Special and .45 Long Colt; they will “do a dance” on a dangerous snake, making the gun a comforting thing to have handy in camp at night.

Best of all, there’s no messy black-powder cleanup afterwards. Standard cleaning procedures are fine. Black powder is corrosive and guns fired with it must literally be washed with soapy water every time they’re used. Smokeless powder is very gentle and a revolver using it can be safely left for days before cleaning.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |

The Centennial Commemorative of the American Civil War in 1960-65 gave rise to a new product for shooters: close replicas of the percussion-fired weapons used in that conflict, both rifles and handguns. Replicas were far less expensive than original guns and as a bonus they were much stronger, thanks to better materials and modern engineering practices. They quickly became popular items. Then the “Cowboy Action Shooting” (CAS) game of 20-30 years later made reproduction revolvers even more popular, and along the way created a new niche product: replacement cylinders to convert them to safe use with fixed ammunition loaded with smokeless powder.

The Centennial Commemorative of the American Civil War in 1960-65 gave rise to a new product for shooters: close replicas of the percussion-fired weapons used in that conflict, both rifles and handguns. Replicas were far less expensive than original guns and as a bonus they were much stronger, thanks to better materials and modern engineering practices. They quickly became popular items. Then the “Cowboy Action Shooting” (CAS) game of 20-30 years later made reproduction revolvers even more popular, and along the way created a new niche product: replacement cylinders to convert them to safe use with fixed ammunition loaded with smokeless powder.