Sixty-plus years ago, when I was a callow stripling with an interest in guns and shooting I religiously read the gun magazines of the day, most especially Gun World. The so-called Cold War was in full swing, people were genuinely concerned about nuclear war and the post-apocalypse world that would result. Gun World, and likely enough other shooting magazines, took advantage of this situation to publish articles on the general subject of "What gun should I have when the shit hits the fan?" Two titles in particular I remember were "Guns For Survival" and "Reloading To Live."

Anyone who pays attention to the various gun sites on the Internet knows this is a perennial theme even now. While we may no longer be too worried about a nuclear Holocaust, there are other situations in which it might be worthwhile thinking about such matters. Over the years as my shooting and gun knowledge has developed, so have my ideas about what gun I might like to have for when "the shit hits the fan." Mark you, I'm very, very unlikely to have to put these ideas into practice, but given the incidence of rioting and disorder in some of our major—and minor—cities, perhaps thinking along these lines may have some value. What characteristics should a SHTF handgun best have?

First, it should be in a common caliber that can be obtained readily, even if you have to sift through the rubble of a gun shop or Wal-Mart after the rioters have passed on to the Target store nearby. This would include .357 Magnum, .38 Special, certainly 9mm Parabellum, and .45 ACP. Not many others.

Second, it should be durable, simple to operate, and easily repaired.

Third, it should be easily obtainable. Preferably without a lot of paperwork and bureaucratic hassle.

Fourth, it should be versatile. There's no telling in what situation(s) it might be needed. Leaving aside the question of quelling the desire of potential looters to see your home as a possible target, it might well be useful for food collection.

Fifth, on the subject of deterring potential assailants or looters, it ought to be something intimidating to the eye: nothing turns a man's mind to the contemplation of his own mortality than someone waving a huge gun in his face.

Now, there are many, many guns using fixed ammunition that meet these criteria. My personal opinion is that with respect to centerfire handguns meeting all these criteria (except perhaps the third, depending on where you live) would be a Ruger Vaquero in .357 Magnum, equipped with a spare cylinder in 9mm Parabellum. That would just about cover all the bases.

However, I want to cover the subject in the sole context of revolvers nominally designed for use with loose black powder and bullets, i.e., black powder guns. There are some on the the market that will serve, plus they have some advantages that a more conventional choice lacks.

I'll start with my third criteria: ease of acquisition without a lot of government hoo-hah. Guns using "loose powder and ball" are specifically exempted from the never-sufficiently-to-be-cursed Gun Control Act of 1968 and its regulations. They are not regarded as "firearms" under Federal law, and can be purchased quite legally by nearly anyone, even by "prohibited persons" disqualified from buying conventional firearms. While a few states have more restrictions, most don't. There are those who deplore this situation but it's the way the law is written. So unless you live in some benighted anti-gun hell-hole like New Jersey, New York, or Illinois, if you want one, you can buy it. Through the mail if you can't find one locally.

Black powder revolvers are inherently versatile, not least because they can be used with varying charges of powder and/or projectiles ranging from round balls to conical bullets. Use small charges for small game, and bump the charge up for bigger stuff, those with four legs (or two). Furthermore, it doesn't even have to be "real" black powder. There are many "replica" powders on the market. It's beyond the scope of this essay to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of "real" versus "replica" powders, but be aware that the latter exist and can usually be found in any large sporting good store, while "real" BP can't.

Another aspect of their versatility is that many BP revolvers will accept "conversion cylinders" to use fixed ammunition. Nor are these cylinders regulated by the Feds or the states, however much our enemies wish that weren't the case. Conversion cylinders are made for many popular models of BP revolvers. They come in a variety of calibers from .32 to .45; and 99% of them require no gunsmithing. They just drop in to replace the BP cylinder and off you go, thanks to the miraculous precision of CNC machinery.

Convertability to fixed ammunition is a real plus. As an example, shotshells can be found in .38 to .45, allowing the gun to be used on small game if or when foraging becomes necessary. They won't compare to a shotgun but they do work, when used within their limitations. If fixed ammunition of the proper caliber happens to be in short supply, you can always put the BP cylinder back in.

They're pretty simple mechanisms, too. Nearly all BP revolvers in today's market are single-actions based on old designs. This isn't a drawback. Single-action revolvers have been used for personal protection and hunting since they were invented; they are no less useful today than in 1873. (The only double-action BP revolver I'm aware of is the Starr; if my experience with one of these is anything to go by, it's not one I would recommend.) The old-style single action mechanism is about as simple as it can be, with few moving parts. If somehow the mechanism becomes damaged it's usually easy to repair, even with limited gunsmithing skills: replacing springs or most small parts is simple. If need be a single-action revolver can be fired by banging the hammer spur with a stick.

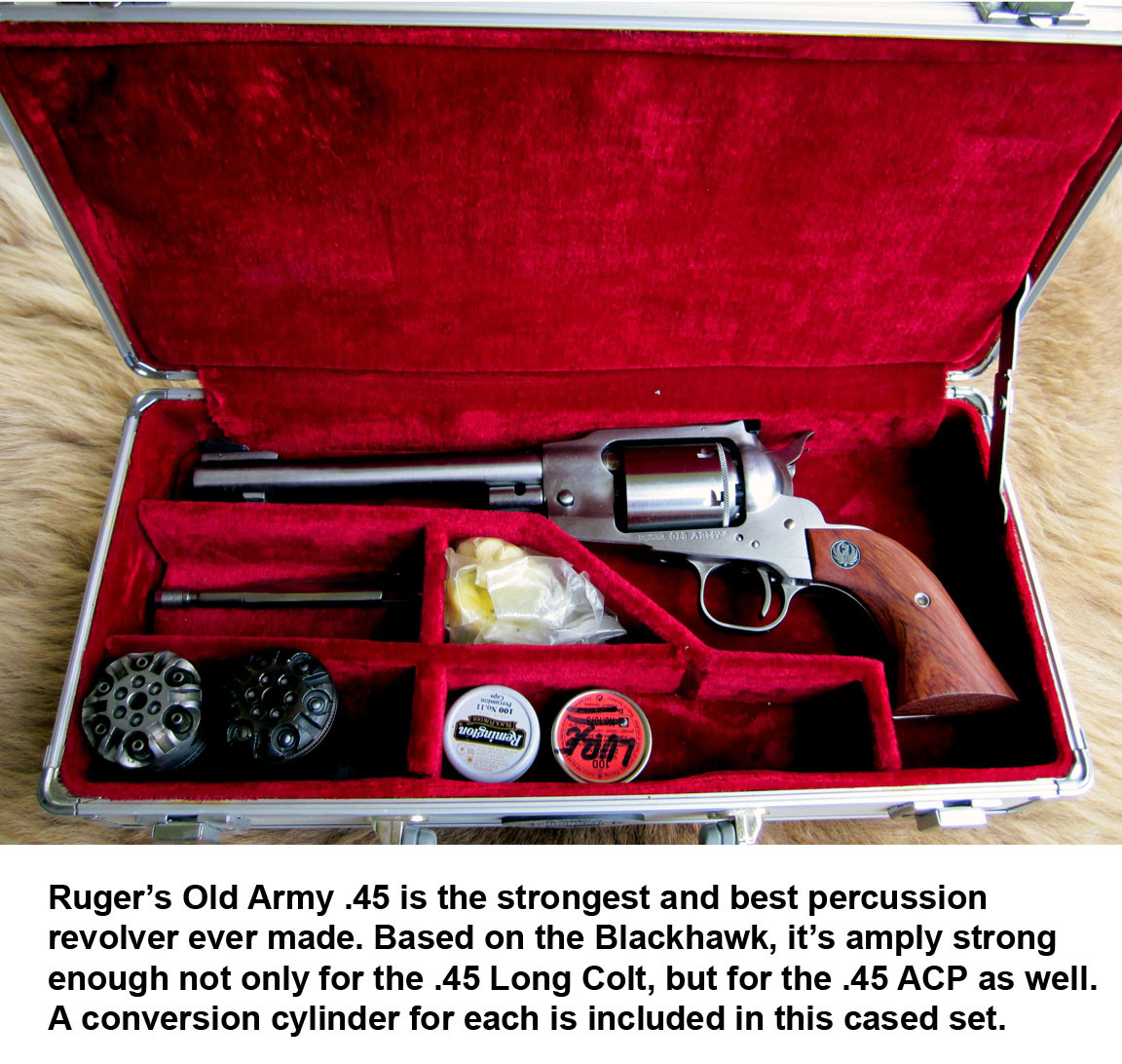

By far the most popular BP single actions are copies of the Remington Model 1858 and the Colt Model 1860 Army or Model 1851 Navy. Companies making conversion cylinders always produce them for these two models. So far as I know, no one has ever made a conversion cylinder for the double-action Starr: it was never as popular as the M1860 and M1858, and in truth wasn't much of a success even in the 1860's. At least one company makes conversion cylinders for the Ruger Old Army (shown above) of which gun, more below.