By medicine life may be prolong’d; yet Death will seize the doctor, too.

– William Shakespeare

Cymbeline, Act V, Scene 5

It comes to all of us in time: the moment when we’re compelled to admit our own mortality and  think about what we should do with material objects, most especially those which have fascinated us, enriched our lives, and given us a means to pursue adventure. Humans tend to get attached to “things”; guns and hunting equipment in particular often acquire a personal emotional significance that’s hard for those who don’t shoot or hunt to comprehend. Nevertheless, it’s a reality. Think about that first .22 rifle you found under a Christmas tree as a youngster, of the shotgun bequeathed to you by a revered grandparent or uncle, or a firearm you may own that’s connected to some major event in history. These aren’t just “things,” they’re symbols of personal achievement or markers of life’s milestones. Since given even minimal care, a gun will likely long outlast its owner, it isn’t a trivial matter to consider what you’ll do with yours when it’s time to quit, and what should happen when you’re no longer able to use or even keep them.

think about what we should do with material objects, most especially those which have fascinated us, enriched our lives, and given us a means to pursue adventure. Humans tend to get attached to “things”; guns and hunting equipment in particular often acquire a personal emotional significance that’s hard for those who don’t shoot or hunt to comprehend. Nevertheless, it’s a reality. Think about that first .22 rifle you found under a Christmas tree as a youngster, of the shotgun bequeathed to you by a revered grandparent or uncle, or a firearm you may own that’s connected to some major event in history. These aren’t just “things,” they’re symbols of personal achievement or markers of life’s milestones. Since given even minimal care, a gun will likely long outlast its owner, it isn’t a trivial matter to consider what you’ll do with yours when it’s time to quit, and what should happen when you’re no longer able to use or even keep them.

Ultimately there are really only two options: either you sell them or you give them away. The decision about which course of action is best is based on many considerations, not least of which is just how to pass along not only the objects but the values and tradition they represent.

If you decide to sell your guns, recognize that you probably aren’t going to make much if any money. It’s certainly not impossible, but unless what you have to sell is something you bought many years ago with intrinsic appeal to collectors or shooters, or something whose commercial value has risen well beyond the inflation-adjusted price, you’ll probably break even at best. A realistic attitude about the commercial value of a gun you want to sell is important. Many pricing guides are available, both in print and on line, and they’re kept reasonably up to date, but in the end they’re only guides. “Book value” is a fluid concept: any given firearm may sell for less or more than “book” depending on uncontrollable factors. The region of the country in which you live, the laws that apply to what you want to sell, the time of year, and most of all rarity and condition, all affect the price you’ll get. No price guide can take all these factors into account in making estimates. It pays to use a guide but as the saying goes, “It’s only worth what someone will pay,” so it’s advisable to follow sales of similar items at on-line auction sites, and in shops. What you’ll get is what someone thinks the gun is worth to him or her, not what it’s worth to you.

If you decide to sell your guns, recognize that you probably aren’t going to make much if any money. It’s certainly not impossible, but unless what you have to sell is something you bought many years ago with intrinsic appeal to collectors or shooters, or something whose commercial value has risen well beyond the inflation-adjusted price, you’ll probably break even at best. A realistic attitude about the commercial value of a gun you want to sell is important. Many pricing guides are available, both in print and on line, and they’re kept reasonably up to date, but in the end they’re only guides. “Book value” is a fluid concept: any given firearm may sell for less or more than “book” depending on uncontrollable factors. The region of the country in which you live, the laws that apply to what you want to sell, the time of year, and most of all rarity and condition, all affect the price you’ll get. No price guide can take all these factors into account in making estimates. It pays to use a guide but as the saying goes, “It’s only worth what someone will pay,” so it’s advisable to follow sales of similar items at on-line auction sites, and in shops. What you’ll get is what someone thinks the gun is worth to him or her, not what it’s worth to you.

Legalities

One thing to keep in mind is that any transfer of a firearm must be done with strict compliance with both federal and state law. If a friend or relative wants to buy the gun, and he or she is a resident of the same state you are, usually you can sell it directly. Federal laws generally don’t apply to intrastate private party transfers; and while in most states no paperwork is required for a direct private party transfer in some it is, so find out. Anything that crosses a state line must go to and through a license holder unless it’s a legal “antique” as defined in the Gun Control Act of 1968—and a few states even require paperwork on antiques.

The Mechanics Of A Sale

Most of us don’t “invest” in guns, we buy them because we like them without any real thought of making money on them. Over the course of an active lifetime in the shooting sports we tend to acquire a number that are “just guns,” with no special personal significance. These are the easy ones: you sell them for what they can bring. There are several ways to do this. Perhaps the best option is to sell directly to friend who’s expressed admiration for one of them and is interested in buying it. If you belong to a shooting or hunting club, an offer sent to the general membership is another good way to find a buyer who’ll be known to you as trustworthy and legally able to own the gun you want to sell.

Be very wary of using newspaper advertisements or “penny-saver” type newsletters. Regrettably a lot of shady characters routinely scan these hoping to find a gun for sale with no paper trail and no questions asked. If you do decide to try such an ad, always demand identification and proof of residency and eligibility; always check the validity of an address or phone number on publicly available databases. If you smell a rat, turn the offer down: the faintest whiff of illegality should send you running like a scared deer. This caution also applies to some on-line listing sites. There’s at least one such specifically dedicated to firearms sales which in my experience is frequently a source of problems. It tends to attract scammers and potentially illegal buyers. If you use any listing site that creates a direct contact between seller and buyer be very, very cautious about whom you deal with and absolutely insist on a face to face meeting. Never deal with an unknown buyer any other way. People can be and have been held liable for criminal acts committed with guns they sold without “due diligence,” so it’s far better and safer to deal with someone you know personally or to route the sale through a dealer who can take care of the legal niceties.

Dealer Consignments

If you haven’t got a friend or acquaintance who’s a potential buyer, consider a consignment or auction sale. Sometimes a dealer will offer to buy a gun outright and enter it into his shop’s inventory, but consignments are a better deal for him because he doesn’t have to invest anything in the gun up front.

Consignment sales via a local gun shop are pretty much hit-or-miss affairs: sometimes the gun will sell immediately and sometimes it will languish for months or years before a buyer comes along. The larger the shop the bigger its customer base, and the better the chance of a quick sale. You’ll have to pay a fee or a commission to handle the sale for you. A dealer earns his money by providing safe storage and following all legally-required steps for a transfer including a background check. The risk that a consigned gun might end up in the hands of a prohibited person is minimized, and any potential liability risk is transferred to the dealer.

When you bring the gun to him you and the dealer discuss the price you want to get, and he considers what his profit should be. Ideally he’ll have a fairly good idea of the value of the gun in his market and he’ll be able to advise you about a realistic net amount to expect from the sale after his expenses and commission are covered. Once a deal is struck the dealer will log the gun into his “bound book,” and upon selling it he’ll log it out again to the buyer. This ensures not only that the law is followed, it insulates you from a buyer who comes to regret his purchase (it happens) and demands a refund.

An FFL dealer’s commission can range from 10-25% but sometimes the percentage can be negotiated. A large gun shop with a good client base will be likely to expose the gun to great numbers of possible buyers. If the shop owner attends gun shows, thousands of potential purchasers may get a chance to see and perhaps handle it. It’s generally not a good idea to sell at a gun show by paying for a table and doing it directly. It’s perfectly legal to do this, but it opens you up to a number of hazards including direct liability for a sale to a prohibited person and you incur a cost to rent a table. Another very unfortunate risk is that sometimes plain-clothes police or BATF agents will cruise a show with the deliberate intention of trapping an unwary private seller into a “straw man” sale. One or two states will allow private parties to use their background check system, but most don’t. Since you likely won’t know your buyer personally at a show, better to let a licensee handle such sales. If you get caught in the trap it will be very expensive and difficult to escape charges for an “illegal” sale. The complexities of firearms laws vary from state to state and the ins and outs of the federal law are difficult for a non-licensee to navigate. Play it safe at gun shows.

One drawback to a dealer consignment is that if you later decide not to sell and to recover your gun (this possibility is always included as part of the agreement) you’ll have to go through the background check and any other legal steps, just as if you were buying it for the first time. It seems absurd that someone should have to jump through legal hoops to retrieve his own property, but that’s the way the law is written: nobody says it has to make sense.

Auction Sales

Another option is to sell at an auction, either live or on-line. Many local auctioneers specialize in firearms sales. A lot of them participate in a nationwide on-line auction listing service by which people all over the country can use the Internet to place bids. All of the very large well-established firms that typically handle high-dollar collectors’ guns do this, but a lot of small houses do so as well. The on-line aspect of such auctions can potentially expose the gun to tens of thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands—of likely buyers. Usually such auctions are conducted not just on line, but simultaneously with a live auction for the same items. The real money is in the on-line bidding because so many more bidders can be accommodated. This is a good option if you’re selling a very rare, fully provenanced gun with a connection to some famous person because really valuable collector guns should get as much exposure as possible to affluent bidders.

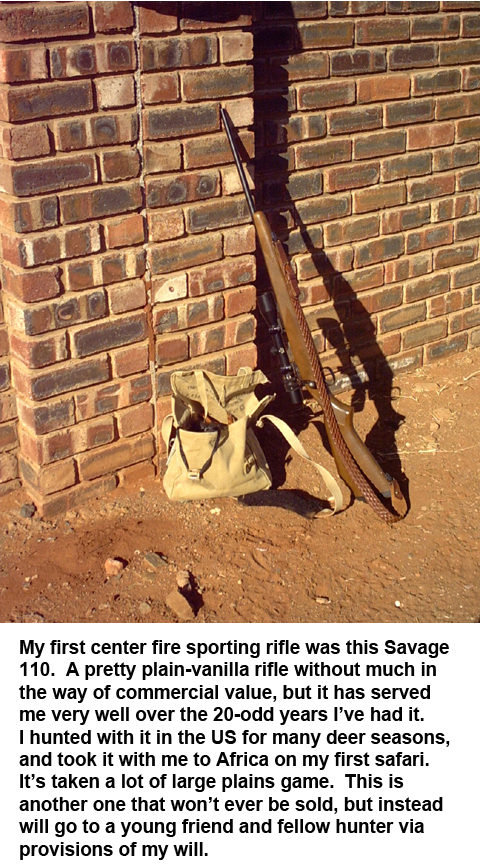

The big name houses provide just that. If you’re lucky enough to own such a firearm one of the high-end houses is probably the best sales venue while it wouldn’t be for a plain-vanilla, run-of-the-mill mass produced gun. If your grandfather brought home a mint-condition Luftwaffe-issue drilling with its original case and accessories from World War Two, one of the “name” houses is your best bet. For most people and most guns it isn’t.

The drawbacks to any auction (especially for non-collector guns) are steep sales commissions that run 18-20% and the fact that auction houses invariably charge an additional “buyer’s premium,” which may push the final price the gun out of the reasonable range. It’s one thing if you’re selling a genuine Colt Model 1860 Army with an iron-clad provenance (and preferably a factory letter of origin) that belonged to one of your ancestors who fought in the Civil War and whose use in a major battle can be proven. It’s quite another matter if you’re offering a modern mass-produced gun.

Let’s say you have a RemChester autoloading shotgun that you feel is—and likely is—well worth $350.00. You consign it to a medium-sized auction house, who put it into their upcoming sale, with “no reserve,” that is, a starting price of whatever the first bidder thinks is a good deal. The gun garners bids. If you add to that $350 the 18% you have to pay in sales commission, you’d actually net only $287…but the buyer pays the auction house the $350 plus another 20% plus shipping to his local FFL holder, plus a fee for a background check. That $350 shotgun, from the buyer’s viewpoint, is now a $420 shotgun, before shipping and FFL fees are added. Tack on another $50-100 and many potential buyers will simply pass it by.

There are other auction options. Several well-established on-line listing services are run on an auction basis. They’re called “auction sites,” but they aren’t really, because they don’t take the gun into possession and sell it for you as a surrogate. You retain it in your possession and list it on the site. When the on-line auction is completed you ship the gun to a receiving FFL holder and he takes it from there. These services are preferable to the direct-contact sites because normally a bidder has to be registered with the site, some degree of credit checking has been done, and the mechanics of the actual transfer nearly always involve using a dealer to handle the final step.

Commissions at on-line listing sites are fairly low, ranging from 2.5-5%. Let’s go back to that $350 shotgun: assuming you pay the listing service 3% you’ll net about $340. You can legitimately ask for the buyer to pay a reasonable shipping charge to send it to his Federal Firearms License (FFL) holder for final transfer. One snag is that if you’re not an FFL holder, when you come to ship it you may run into a stubborn licensee who simply won’t accept a gun from a private party. Some insist it come from another FFL holder—which is not required by federal law though some states have this provision in their codes—so you get stuck with transfer and service fees at your end. Federal law clearly and specifically allows a dealer licensee to accept a firearm in interstate commerce from anyone, but some shop owners simply don’t care what the law says and won’t do it. It’s always best to make a specific point in your ad that the buyer should assure that his chosen transfer agent is willing to accept the gun directly from a private party. Another problem is that if the buyer is dissatisfied (he is, after all, buying the gun sight unseen) and wants to return it, you’ll have to go through all the rigamarole with a transfer at your end just to get it back.

When you reach the point of shipping to the dealer, be aware that unlicensed individuals can ship long guns via the US Postal System, but not handguns: those have to go by common carrier. This is usually at a modest additional cost compared to the USPS but private carriers typically have better tracking and notification than the USPS and in my opinion are worth what they cost.

On all of the large on-line listing-service sites there will be a few high-volume sellers who work on a reasonable commission basis. Instead of listing a gun yourself you ship it to one of these FFL dealers and have him sell it for you via the site. Such second-party sellers typically have a very high reputation among the site’s users and will almost always get a higher final price than you as a private seller would, even if they put the gun up at a very low start price. If you decide to use a second-party seller pick one who does a really good job with photography: good pictures sell guns faster than any other factor in on-line auction, and good gun photography is an art. Look over a listing-service site to get a feel for who the “best sellers” are and how they present consigned items. Second-party sellers charge a commission in the range of 10-18% depending on the final value, but they not only offer the same advantages of a local dealer, they have a larger reach thanks to the national coverage of the sites they use.

Ammunition

Disposing of ammunition is marginally simpler than firearms. You can include it in the price of the sale, which is usually a good idea if the gun fires some oddball caliber that’s not easy to find. Most states have no laws against buying “mail order” ammunition but a few do. In those cases the stuff has to go through a state-licensed dealer, which adds expense. Better to sell it—or give it away—locally if your buyer is in one of these states. The on-line listing services will usually have a listing category specifically for ammunition; alerting your club or relatives to its availability is also a good idea.

I’ve sometimes regretted selling a gun, but I’ve given away quite a few and I’ve never regretted doing that. There are many reasons to give away a gun, not the least of which is that making it a gift really serves the shooting community as a whole. You don’t get any money out of it, but it’s a form of “investment” in the future of the shooting sports. It’s a regrettable fact that in recent decades the number of active hunters and shooters has declined as the population has aged; furthermore, the constant demonization of gun ownership by the press and broadcast media has become ever more ferocious as they campaign to make the shooting sports socially unacceptable. By passing a treasured firearm along to a new generation you help perpetuate time-honored activities. The recipient of the gift immediately becomes a vested, active participant in the fight to maintain the right to keep and bear arms; and to continue the traditions of hunting and field sports.

Who Gets What?

In some ways giving away a favorite firearm is like finding a new home for a pet you can no longer keep. You want to know it will go to someone who’ll cherish and care for it properly. Likely enough you already know someone who’d be a good choice: a son, daughter, niece, nephew or grandchild. Perhaps you mentored him or her and feel the time is ripe. If you do, there’s no better time than right now to make the gift. If you’ve had the thought that one of your younger relatives or friends would appreciate the gift, go ahead.

Even if you don’t have a relative in mind there are other options. Perhaps you’re actively involved with firearms or hunter training as a Hunter Education Instructor, or you’re a summer camp or high school rifle team coach, a Scout troop merit badge counsellor, or a mentor for a 4H club. Organizations committed to training young people in shooting have active programs that will welcome donations of firearms and ammunition. They’re especially appropriate recipients of donations of small-caliber rifles and simple shotguns for training. Such organizations are a fine contact point and a conduit to young shooters as well as an excellent way to encourage participation in the sport; not incidentally a gift like this safeguards you from the standpoint of personal liability.

Probably there’s a chapter of the Friends of NRA not far away from you. This non-profit group is specifically dedicated to encouraging youth shooting. There are other worthy hunting and conservation-based charities including Ducks Unlimited, Quail Unlimited, Rock Mountain Elk Foundation, Izaak Walton League, and many others with youth programs. Local chapters typically raise money through annual banquets with raffles and games. Donating a gun as a prize advances the cause directly as well as giving you as the donor a small tax deduction.

One of the best and most satisfying ways to pass on a firearm to those will truly appreciate it is to give it to a museum, something that’s especially appropriate when it has significant historic or collector value. I once owned a No. 1 Mark III Lee-Enfield rifle that had been manufactured at the Small Arms Factory in Lithgow, Australia in 1923. Very few SMLE’s were made in Lithgow that year; somehow the Small Arms Factory Museum learned I owned it, tracked me down and asked if I would send it to them to complete an elaborate display that was to be the centerpiece of their collection because even the factory didn’t have a 1923 example. I was happy to do so and shipped it to them. I’m very satisfied because that little piece of history “went home” to the place where it was made and perhaps the Aussie soldier who carried it into battle may someday see it!

Some museums are specialized, their gun collections associated with various eras or events in our country’s history. All of them will happily take donated guns. Museums dedicated to commemorating the Civil War or the westward expansion are obvious places where guns of those eras would be welcome gifts should you own one. Other museums are less specialized, but very prestigious and professionally run. The National Firearms Museum in the suburbs Washington DC has a vast collection open to the public. Most of the NFM’s collection—only a part of which is actually on display—came to it via donation. I’ve sent them several guns, including one I inherited from my late father-in-law. This is a rather scarce Sauer und Sohn “Behordenmodel” pistol that he brought home as a war souvenir in 1945. I gave it to the NFM in honor of his service to the country and I could think of no more fitting place for it to be. That pistol is now part of their World War Two display and I take considerable satisfaction in knowing that it’s not only properly curated, but that it’s also safe from those whose hatred for all guns would lead them to wantonly throw such artifacts into a smelter.

There isn’t a better example of how a museum donation can save a historic artifact from destruction than the most famous hunting firearm ever: the Holland and Holland double rifle President Theodore Roosevelt used on his famous 1909 safari. It’s now a prominent display item at the Frazier Museum of History in Louisville, Kentucky, a tangible connection between today’s public, the life and legacy of a great man, and a long-gone era. It is preserved forever thanks to the generosity of its former owners.

Let’s face facts: none of us are getting any younger, and our hobbies and interests are in danger. It’s imperative that we plan for the future, that we do whatever we can to save those things and those traditions we revere. We must leave a real legacy for the next generation, to ensure there is a next generation of shooters and hunters. Honest and serious contemplation of how best to let go of today’s tangible possessions is an essential part of protecting the intangible values we all share.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |