This is a cautionary tale, a story of the price of carelessness, both in money and in suffering. In the end things worked out, but getting to the end required hard feelings, wounded pride, and a wounded animal. Things turned out to my advantage, but I wish they’d gone some other way.

It happened on the first full day of a four-day hunt on a large ranch in the

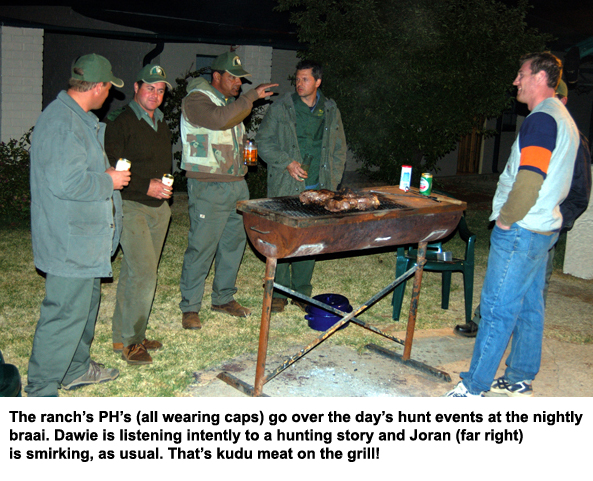

One of his sons, Joran, was in the party. Joran was then something of a ne’er-do-well; not a bad kid, really, but as he headed into his mid 20’s he was still drifting, jobless, and unsure of what he wanted to do with life. A handsome devil, apparently very successful with the ladies; a smart-ass who was something of a frustration to his very accomplished and respected "Old Man." At Denys’s insistence he was taking a few practical courses at the local technical college, but chatting with him revealed he hadn’t much in the way of concrete plans for what came after that. He was having fun and that was all that mattered to him.

I don’t know how much previous hunting experience Joran had, but I do know that he was enthusiastic about the trip, and wanted to get a kudu bull. Denys had allowed him to come, perhaps as an inducement to get his act together. Equally likely he saw it as a chance for some father-son bonding and "learning by example" from the rest of the hunting party, professionals all. They included Denys’s older son Piet; his son-in-law Dawie, an independent businessman; and three Americans: me, my regular hunting partner Rick, and Art, all of us senior university faculty. Rick and Denys were old friends and had hunted together in Africa before: I had hunted with Rick for years in the

At dinner the evening before we went into the veld, Joran, who for some reason seemed to dislike Americans, made a few snide cracks which Rick, Art, and I ignored. I didn’t take them personally: they were merely the traditional attempt of Youth to goad Old Age into over-reacting. It's never good policy to respond to such provocations, however rude they may be, when you’re a guest. Twice true when you’re a foreigner as well. Taking offense would simply reinforce the peculiar beliefs many non-Americans have about us that come from watching too many imported soap operas and too much CNN International. We let the needling go without comment.

At dinner the evening before we went into the veld, Joran, who for some reason seemed to dislike Americans, made a few snide cracks which Rick, Art, and I ignored. I didn’t take them personally: they were merely the traditional attempt of Youth to goad Old Age into over-reacting. It's never good policy to respond to such provocations, however rude they may be, when you’re a guest. Twice true when you’re a foreigner as well. Taking offense would simply reinforce the peculiar beliefs many non-Americans have about us that come from watching too many imported soap operas and too much CNN International. We let the needling go without comment.

I was having a great trip. The guns had come through Customs without a hitch, the sight-in session on the day before hunting went well, and in the first few hours of the day I’d made a one-shot 90-meter kill on a gemsbok cow. I was feeling pretty good! Back at the lodge for lunch, I heard Joran grousing: Piet had killed a kudu cow that morning, but Joran had fired at a bull at what turned out to be about 300 meters, with no visible effect. I took some not-entirely-good-natured ribbing from Joran for having killed a cow, but again, wrote it off to youth, inexperience, and a desire to poke fun at any American who came within range. That afternoon, I went back out with my guide Hein and tracker Twasi to see what else we could find.

The afternoon was a good bit slower than the morning had been, but I was having the time of my life tramping through the veld, and didn’t care whether I killed another animal or not. The gemsbok was the biggest thing I’d shot in my life up to that point, and I was pretty pleased. To me a 200-pound whitetail buck is a real monster, and that gemsbok was at least one and a half whitetail-equivalents, so I was at the top of my game. I’d come to

The three of us tramped around for several hours without seeing anything, and finally I suggested we find a comfortable spot that would serve as an impromptu hide, and see what came by. Hein and Twasi were both agreeable, so about 4:00 PM we parked ourselves under a tree, watching what Hein said was a game trail, and quite companionably waited as the day came to an end.

Twasi was a handsome young guy from a local tribe, an employee of the ranch owner in some capacity I never really learned. He had unbelievable eyesight: I’m told that this is a pretty common thing among his people, and that those who have it are said to be “born for the bush.” I don’t know if he was literate, but if he were he could probably have read the lettering on a dollar bill from 100 yards away. His vision was simply phenomenal. Mine isn’t bad (when I have my glasses on!) and I’m pretty good at spotting movement in the woods, but what happened next was entirely to Twasi’s credit. Just as dusk was falling, roughly an hour after we’d stopped, he quietly hissed, “Kudu!”

I had no idea where it was. I looked where he was pointing and saw…nothing. Just leaves and brush. I thought Twasi was hallucinating, but he was (very quietly) insisting that there was a kudu bull right there, Boss, and obviously exasperated that this bespectacled geezer couldn’t see what to him was a plain as a billboard. I took some comfort in the notion that Hein couldn’t see it either, but Twasi was certain there was a kudu about 150 meters away.

Finally, though, when the bull moved, I did spot him, and from then on never let my eyes leave him as he slowly ambled along from left to right, browsing from the trees he passed. Kudu are strikingly beautiful animals, and they have coloration that in the open looks like it wouldn’t hide them, but in the bush, they simply vanish as soon as they stop moving. If I’d looked away for even a single second and he stopped, I’d have lost him again.

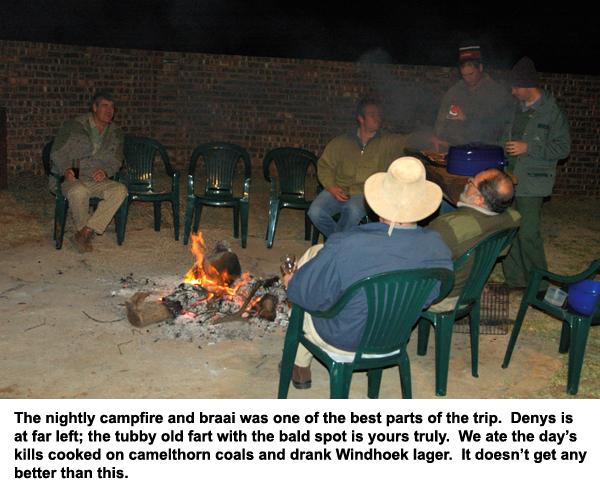

This one, however, was moving, and I had my eyes riveted on him. I wasn’t about to lose sight of him again because I had plans for that evening, involving a braai, some

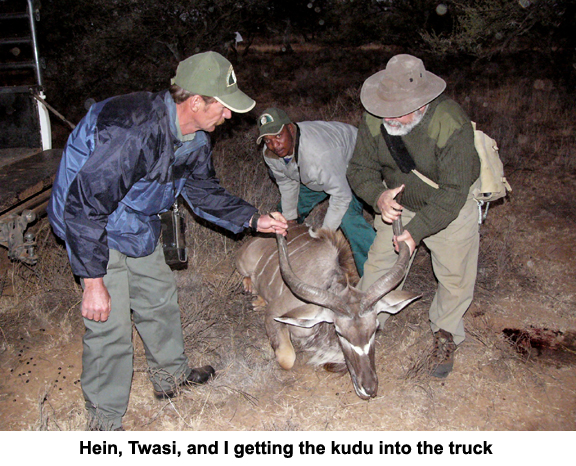

He fell with an audible thud, and through the deepening twilight we could hear a long, mournful moan, a sound of indescribable pathos that I’d never heard before. Hein slapped me on the back, and told me this was the death moan of an animal killed with a single shot to the heart. And so it proved: when we reached him he was stone dead, the bullet having hit exactly where I wanted it to.

He fell with an audible thud, and through the deepening twilight we could hear a long, mournful moan, a sound of indescribable pathos that I’d never heard before. Hein slapped me on the back, and told me this was the death moan of an animal killed with a single shot to the heart. And so it proved: when we reached him he was stone dead, the bullet having hit exactly where I wanted it to.

He wasn’t a “trophy” animal by the “book” standards, quite clearly a bit of a youngster. I have no idea how to age kudu, but my guess is he was about 2 years old. I was pleased as punch, though, and didn’t give a damn that he only had one-and-a-half curls: he was a kudu bull, and that was that. Two big antelope in a single day!

Hein called for the baakie and we took the obligatory pictures. I noticed that the bull had some sort of gash on his left foreleg, but didn’t think much of it at the time. It wasn’t until we were back at the lodge and the process of skinning and gutting had begun that I understood the significance of that gash. It was a seething Joran who explained it to the American interloper through his gritted teeth, and suppressed anger.

This was the kudu he’d fired at that morning! Joran wasn’t terribly knowledgeable about ballistics, and I suppose he had a touch of buck fever when he took the shot. He had forgotten about the drop of the bullet. His rifle was sighted to hit about 3 cm high at 100 meters, like everyone else’s; but the bull had been three times that far away. The bullet from Joran’s .308 had hit the bull: but it had hit him very much lower than intended. Instead of striking him in the chest, the bullet had gone through the meat of his right foreleg, perhaps 18” low, drilling a neat hole without touching the bone. On the way out it nicked the skin of the left foreleg, leaving not much more than a bad scratch. I imagine that bull was pretty unhappy.

This was the kudu he’d fired at that morning! Joran wasn’t terribly knowledgeable about ballistics, and I suppose he had a touch of buck fever when he took the shot. He had forgotten about the drop of the bullet. His rifle was sighted to hit about 3 cm high at 100 meters, like everyone else’s; but the bull had been three times that far away. The bullet from Joran’s .308 had hit the bull: but it had hit him very much lower than intended. Instead of striking him in the chest, the bullet had gone through the meat of his right foreleg, perhaps 18” low, drilling a neat hole without touching the bone. On the way out it nicked the skin of the left foreleg, leaving not much more than a bad scratch. I imagine that bull was pretty unhappy.

Joran was mightily honked off, and I heard him griping to Piet and David (in a voice loud enough to make sure I heard him), “I don’t believe it! The Gray Ghost of  and kills one on his first try! Nobody does that!” Well, I had, and perhaps my long experience with whitetails (who are every bit as ghost-like as any kudu) had something to do with it. Some of it was dumb luck; some of it was being persistent enough to stay in the field as long as I could; some of it was that inner sense of something’s-going-to-happen that all hunters know; and much of it was Twasi’s fantastic eyesight. But in the end, the result was undeniable. Joran and I had tried for the same animal: he’d failed and I hadn’t. The critter being gutted and skinned was my kill.

and kills one on his first try! Nobody does that!” Well, I had, and perhaps my long experience with whitetails (who are every bit as ghost-like as any kudu) had something to do with it. Some of it was dumb luck; some of it was being persistent enough to stay in the field as long as I could; some of it was that inner sense of something’s-going-to-happen that all hunters know; and much of it was Twasi’s fantastic eyesight. But in the end, the result was undeniable. Joran and I had tried for the same animal: he’d failed and I hadn’t. The critter being gutted and skinned was my kill.

That’s when Denys came up to me and explained the rules of African hunt etiquette: the guy who wounds an animal has to pay for it, whether he later collects it or not. Though it was my kill, it was Denys’s bill. His son was there at his invitation, he was paying for Joran’s hunt, and he would pay for the kudu.

I was shocked. I protested, and told Denys that I was perfectly prepared to pay for the animal, that I had budgeted for several kills (how’s that for optimism?) and since I’d done the deed, I should pay. Though he was clearly livid with Joran’s carelessness and his ready acceptance of a “miss” that wasn’t one, Denys was insistent. He would pay the rancher for the kill, “…but I’ll get it back out of my son, that I promise you!” I could only yield to his controlled anger on what was obviously a point of honor for him. Denys isn’t a man you want to offend, and he would clearly have been offended had I paid for the bull. He'd have seen it as condoning Joran’s behavior and allowing him to escape the consequences.

That evening at dinner Joran was even more sullen and sarcastic than he had been the previous two days, but again, I ignored it. And in the end, things worked out OK. Since

That evening at dinner Joran was even more sullen and sarcastic than he had been the previous two days, but again, I ignored it. And in the end, things worked out OK. Since

My “free” kudu came at a cost beyond money: nobody involved, really—except me—got off free. Joran paid a price in wounded pride, but maybe he learned a lesson, too. His father had to admit that his son was not yet all he had hoped he’d be, as well as pay the rancher his fee.

The kudu had a full day of suffering. Perhaps he’d have recovered from these flesh wounds and gone on with his life and perhaps not: when the paths of our lives intersected in the dusk, maybe a merciful

Nothing in this world is totally free.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |