THE UNHAPPY DOGS OF INDIA

In 1998 I spent several several months in India teaching at Mangalore University. The incidents described here date from that time; and my memories of them are still vivid and painful. This essay is in remembrance of the poor creatures of whom I write, a sort of apology to them for their fate, and that of so many of their kind.

Stray dogs are everywhere in India, tens of millions of them scavenging in the streets and refuse piles for something to eat. I found this entry in my diary, from January 25, 1998:

Dogs are completely ignored. There are dogs all over the place here, the scruffiest and nastiest-looking mutts you could imagine, worse-looking than even Egyptian dogs. Most of them are lean as a stick and about 20-30 pounds; the main colors seem to be brown and brown and white, though I have seen a few dark ones. In any event, they command no attention whatever. They wander at will and if they happen to pass by a human they ignore him unless he makes some gesture they think might be a threat (I have yet to see someone actually threaten a dog) and then shy away. God knows what they eat. I saw one dog asleep in front of a store where an old man was sitting, looking every bit like Ol’ Blue in front of a general store in Mississippi, but he was just a random street cur and I suppose he and the shop owner had a non-aggression pact: I sleep here and you don’t kick me as long as I don’t try to bite you or go into the shop.

The average Indian ignores stray dogs; indeed, many if not most people are actively afraid of them, with good reason: rabies is endemic in India, which has by far the highest rate of human rabies deaths in the world. Its 20,000 to 30,000 cases account for more than a third of world-wide deaths every year. With rabies a major health threat it’s understandable that any stray dog is regarded with suspicion and fear. But despite being shunned and despised, the dogs I encountered were mostly friendly—if wary—around those few humans who tolerated their presence. That is, of course, the nature of dogs: they want to interact with humans and are unaware that they’re hated and feared.

India has national and state dog and rabies control policies but there are so many other issues to deal with that these programs are underfunded. Furthermore, there is little coordination among different agencies, the costs of the programs are high, and contiguous countries also have endemic rabies. Moreover the type of dog population control—and hence rabies control—seen in western nations is simply impossible in India for a variety of reasons.

The official policy of mass vaccination of strays is at best a drop in the bucket, just a fig leaf. In order to control rabies at least 70% of stray dogs would have to be captured and vaccinated, but vaccinating 14,000,000 to 20,000,000 dogs is a logistic impossibility. To be brutally honest, the only practical way to deal with the threat is to round up and kill stray dogs, and it’s very difficult to find Indians, especially Hindus, willing to do that. Implementing a program of mass canine murder runs counter to the so-called “reverence for life” that’s part of Hindu philosophy. Although many Indians aren’t Hindus, the religious and ethical views of the majority religion permeate all aspects of society, including the government. It’s inconsistent with the “reverence for life” professed as a national ethic to kill millions of dogs, but it’s easy just to ignore and neglect them, even though that’s a particularly subtle form of cruel treatment, really. They are allowed to suffer and die and nobody gives a damn. “Reverence for life” thus becomes a meaningless phrase—a flat lie, really—with reference to dogs; their lives have no value and are not “revered” in any meaningful sense.

Once in Delhi I came across the body of a large black dog who had died on the sidewalk in a major up-scale shopping district. Nobody moved that body out of the way: in a western country it would have been removed very quickly but touching the body of a dead dog is “polluting”; hence until a human of sufficiently low status could be found who would do the job, the dog was left to rot. I saw similar things more than once. It happened on my university campus: three dogs died (of rabies) in two weeks and the bodies were left where they fell, on the pathways students used. They had no more life left to “revere,” not that they had ever been revered at all.

But I want to talk about a few dogs with which I had some sort of minimal interaction, whom I “named” in my mind, and who to this day epitomize for me the cruelty of the “reverence for life” as it was practiced in Mangalore.

On our campus there was a skinny—nay, emaciated—black bitch, who bore a startling resemblance to Anubis, the ancient Egyptian goddess of death. Anubis would wander around a construction site, harming nobody and being ignored. She was just there, a sort of background item. Amazingly enough, Anubis had a litter of five puppies, three of whom had survived. They were black and white with a resemblance to a Border Collie; since I had a Border Collie at the time I took a liking to one of the pups who looked like my dog back home.

On our campus there was a skinny—nay, emaciated—black bitch, who bore a startling resemblance to Anubis, the ancient Egyptian goddess of death. Anubis would wander around a construction site, harming nobody and being ignored. She was just there, a sort of background item. Amazingly enough, Anubis had a litter of five puppies, three of whom had survived. They were black and white with a resemblance to a Border Collie; since I had a Border Collie at the time I took a liking to one of the pups who looked like my dog back home.

I watched that pup develop in her early months,  and if it had been possible I’d have taken her in; cleaned her up, given her proper shots, fed her, and taken her back to the US with me at the end of my tour. Of course that was impossible, and I knew it, but I would have done it in a heartbeat. I did give her a name, the only thing I could give her. One day she managed to get herself covered with tar by falling or jumping into a puddle of it on a campus construction site. It was all over her, most of her body looked like it was painted with the stuff. I thought of her then as “Tar Baby,” and that’s the name I gave her.

and if it had been possible I’d have taken her in; cleaned her up, given her proper shots, fed her, and taken her back to the US with me at the end of my tour. Of course that was impossible, and I knew it, but I would have done it in a heartbeat. I did give her a name, the only thing I could give her. One day she managed to get herself covered with tar by falling or jumping into a puddle of it on a campus construction site. It was all over her, most of her body looked like it was painted with the stuff. I thought of her then as “Tar Baby,” and that’s the name I gave her.

I was certain she would die but she didn’t, at least not of the tar dip. Over several weeks she gradually lost her tar coating as it hardened and flaked off. She lost a big patch of hair on her left shoulder but seemed to be growing new hair in the bald spots. I was glad about that and hoped she might not after all be badly scarred, for all the good that would do her. The last time I saw her, just before leaving India, she was pretty much free from tar. I have no doubt she died fairly soon afterwards of something else, of course, though God alone knows how or where or when. I certainly don’t. But giving her a name in my mind meant that at least she would be mourned by one person even if no one else cared about her.

Tar Baby’s mother Anubis died of rabies. She had been looking pretty bad and staggering around and then started having convulsions, clearly in extremis. Shortly thereafter one of my students came by to tell me that Anubis had died and asked me to ask the Head to see what he can do about removing her carcass. When nothing was done for a couple of days the same student told me she planned to bury Anubis at the site where she died. I suggested she bury her as deep as possible, and remarked that it was a lot of work. “We’ll do it,” she replied, “we can’t just leave her there.” But it never happened because shortly afterwards one of the staff members stopped in to tell me the body had been removed. I don’t know who took it, but I had called the office of the Vice Chancellor and suggested that perhaps a rotting dog dead of rabies was not a good thing to have lying around and presumably they found someone who was low enough in status to remove Anubis’ body and dispose of it. Putting her in a landfill would almost have been a dignified end compared to the short life she’d led, but I suspect whoever took her away just threw her somewhere else for the buzzards to eat. Wherever she was put, she was well out reach of anything more India could do to her.

Tar Baby’s mother Anubis died of rabies. She had been looking pretty bad and staggering around and then started having convulsions, clearly in extremis. Shortly thereafter one of my students came by to tell me that Anubis had died and asked me to ask the Head to see what he can do about removing her carcass. When nothing was done for a couple of days the same student told me she planned to bury Anubis at the site where she died. I suggested she bury her as deep as possible, and remarked that it was a lot of work. “We’ll do it,” she replied, “we can’t just leave her there.” But it never happened because shortly afterwards one of the staff members stopped in to tell me the body had been removed. I don’t know who took it, but I had called the office of the Vice Chancellor and suggested that perhaps a rotting dog dead of rabies was not a good thing to have lying around and presumably they found someone who was low enough in status to remove Anubis’ body and dispose of it. Putting her in a landfill would almost have been a dignified end compared to the short life she’d led, but I suspect whoever took her away just threw her somewhere else for the buzzards to eat. Wherever she was put, she was well out reach of anything more India could do to her.

My student had fed Anubis as a puppy, and told me that when she started to “get fatter” she didn’t at first realize she was pregnant. Tar Baby’s litter was her first and her only one. Anubis probably was not even a year and a half old and I have to ask: what possible function could her life and death have served in anything approaching a rational universe? Ayn Rand argued that reason is the only force that matters; that religion is unreasonable and therefore invalid. I don’t dispute that idea; it’s hard to imagine how a rational God could have any kind of reason for creating the dogs of India and the life they lead, however “revered” that life may or may not be. Damn the “reverence for life” to hell and back.

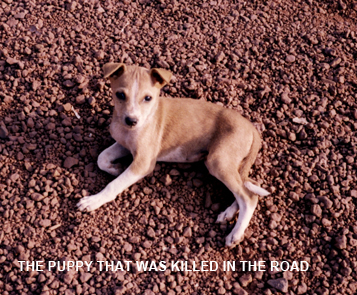

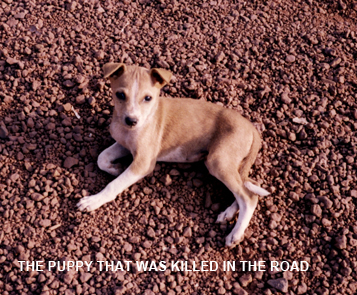

Other strays had puppies, too. One had a batch of brown and white pups, quite engaging little guys, one of whom became the central figure in a horror I witnessed. When the puppies reached the age when they started to explore their world, two of them were playing at the edge of the road by the bus stop in front of the campus. I saw them and and I knew what was going to happen. Inevitably one pup wandered into the road, doing puppy things, and was nailed by a Maruti Jeep that didn’t even slow down, whose driver probably didn’t know he’d hit anything.

Other strays had puppies, too. One had a batch of brown and white pups, quite engaging little guys, one of whom became the central figure in a horror I witnessed. When the puppies reached the age when they started to explore their world, two of them were playing at the edge of the road by the bus stop in front of the campus. I saw them and and I knew what was going to happen. Inevitably one pup wandered into the road, doing puppy things, and was nailed by a Maruti Jeep that didn’t even slow down, whose driver probably didn’t know he’d hit anything.

I saw it coming. I knew it would happen. I had half started to call the pup to me (they were at the stage when they come to a whistle) to get it away from the edge of the road but stopped, because I didn’t want to encourage it to follow people around. I regret to this day that I didn’t act on that impulse; that jeep came out of nowhere, doing about 40 mph, and the pup was caught by the front left wheel, with that sickening WHUPPP! noise, run right over and dead instantly. I knew it was coming. I went and checked the poor thing; it was stone dead. All I could do was to move the body to the side of the road to at least save it from being pulped by more vehicles. This drew strange looks from the people at the bus stop who obviously couldn’t imagine why I had made a disgusted sound when the hit happened; why I’d handle a dead dog, or why I would care. The vigilant crows were at her carcass in less than 5 minutes.

I was tremendously upset by that nameless puppy’s death but on reflection I realized that in a way it was better off. That dog would never fall ill with parasites; never be kicked by a human, and never go hungry. I told myself that it was as fast and as clean a death as it could well have been: the pup certainly died instantly without knowing what hit it. The hit was so perfect I could almost think it was deliberate, but I doubt if it really was; it’s just that if the driver even saw the poor thing, he wouldn’t have bothered to slow down and he certainly wasn’t going to swerve: it was just a dog. At least I’m glad it was killed outright. Had it merely been injured, it would have been harder on me; I would probably have had to kill it myself with my pocketknife, a duty I don’t even like to think about. No one else there would have lifted a finger to help an injured dog, I am certain.

It can be argued that the puppy’s death was part of some master plan, and that we can’t know God’s purpose nor the role any individual animal has to play in His plan. I can’t accept this notion. If Man really was created in God’s image, he must therefore have been given some degree of understanding of God’s goals, aims, and purposes. But there simply can’t have been any “purpose” to Anubis’ short life and death, or Tar Baby’s, of the puppy killed in front of me, or any of the other dogs in that miserable country, dogs who needed humans to live, but whose humans didn’t care whether they lived or died.

Dogs, even feral strays, aren’t wild animals. They haven’t even the degree of free will that truly wild animals have. Dogs are an exception among domestic animals in that they are the only species that is voluntarily domesticated: they live with us because they want to. Dogs are commensals—perhaps even symbiotes—of humans. They cannot live independently of Man and are stuck with us, for better or or worse, “until Death do us part.” For that reason alone they’re entitled to some degree of compassion and concern. To put it in Ayn Rand’s terms, the “value” of dogs is that they are part of Man’s nature, and the preservation of any part of that nature is worth some effort.

This works both ways. Dogs can’t live without us, but neither can we live without dogs for very long. When human colonies are established on the Moon or other planets, there will be dogs there sooner or later; their presence may be justified on the grounds of utility as “sniffers” or “miner’s canaries” or “experimental animals,” but the real reason they will go with us is because Man needs dogs, and will take them wherever he sets down roots. The first animal in space was a dog, Laika; and the first species to accompany Man as he populates space—again, voluntarily—will be the dog. I just hope that their lives will truly be revered and valued in a way that the lives of dogs in India are not.

On our campus there was a skinny—nay, emaciated—black bitch, who bore a startling resemblance to Anubis, the ancient Egyptian goddess of death. Anubis would wander around a construction site, harming nobody and being ignored. She was just there, a sort of background item. Amazingly enough, Anubis had a litter of five puppies, three of whom had survived. They were black and white with a resemblance to a Border Collie; since I had a Border Collie at the time I took a liking to one of the pups who looked like my dog back home.

On our campus there was a skinny—nay, emaciated—black bitch, who bore a startling resemblance to Anubis, the ancient Egyptian goddess of death. Anubis would wander around a construction site, harming nobody and being ignored. She was just there, a sort of background item. Amazingly enough, Anubis had a litter of five puppies, three of whom had survived. They were black and white with a resemblance to a Border Collie; since I had a Border Collie at the time I took a liking to one of the pups who looked like my dog back home.  and if it had been possible I’d have taken her in; cleaned her up, given her proper shots, fed her, and taken her back to the US with me at the end of my tour. Of course that was impossible, and I knew it, but I would have done it in a heartbeat. I did give her a name, the only thing I could give her. One day she managed to get herself covered with tar by falling or jumping into a puddle of it on a campus construction site. It was all over her, most of her body looked like it was painted with the stuff. I thought of her then as “Tar Baby,” and that’s the name I gave her.

and if it had been possible I’d have taken her in; cleaned her up, given her proper shots, fed her, and taken her back to the US with me at the end of my tour. Of course that was impossible, and I knew it, but I would have done it in a heartbeat. I did give her a name, the only thing I could give her. One day she managed to get herself covered with tar by falling or jumping into a puddle of it on a campus construction site. It was all over her, most of her body looked like it was painted with the stuff. I thought of her then as “Tar Baby,” and that’s the name I gave her.  Tar Baby’s mother Anubis died of rabies. She had been looking pretty bad and staggering around and then started having convulsions, clearly in extremis. Shortly thereafter one of my students came by to tell me that Anubis had died and asked me to ask the Head to see what he can do about removing her carcass. When nothing was done for a couple of days the same student told me she planned to bury Anubis at the site where she died. I suggested she bury her as deep as possible, and remarked that it was a lot of work. “We’ll do it,” she replied, “we can’t just leave her there.” But it never happened because shortly afterwards one of the staff members stopped in to tell me the body had been removed. I don’t know who took it, but I had called the office of the Vice Chancellor and suggested that perhaps a rotting dog dead of rabies was not a good thing to have lying around and presumably they found someone who was low enough in status to remove Anubis’ body and dispose of it. Putting her in a landfill would almost have been a dignified end compared to the short life she’d led, but I suspect whoever took her away just threw her somewhere else for the buzzards to eat. Wherever she was put, she was well out reach of anything more India could do to her.

Tar Baby’s mother Anubis died of rabies. She had been looking pretty bad and staggering around and then started having convulsions, clearly in extremis. Shortly thereafter one of my students came by to tell me that Anubis had died and asked me to ask the Head to see what he can do about removing her carcass. When nothing was done for a couple of days the same student told me she planned to bury Anubis at the site where she died. I suggested she bury her as deep as possible, and remarked that it was a lot of work. “We’ll do it,” she replied, “we can’t just leave her there.” But it never happened because shortly afterwards one of the staff members stopped in to tell me the body had been removed. I don’t know who took it, but I had called the office of the Vice Chancellor and suggested that perhaps a rotting dog dead of rabies was not a good thing to have lying around and presumably they found someone who was low enough in status to remove Anubis’ body and dispose of it. Putting her in a landfill would almost have been a dignified end compared to the short life she’d led, but I suspect whoever took her away just threw her somewhere else for the buzzards to eat. Wherever she was put, she was well out reach of anything more India could do to her.  Other strays had puppies, too. One had a batch of brown and white pups, quite engaging little guys, one of whom became the central figure in a horror I witnessed. When the puppies reached the age when they started to explore their world, two of them were playing at the edge of the road by the bus stop in front of the campus. I saw them and and I knew what was going to happen. Inevitably one pup wandered into the road, doing puppy things, and was nailed by a Maruti Jeep that didn’t even slow down, whose driver probably didn’t know he’d hit anything.

Other strays had puppies, too. One had a batch of brown and white pups, quite engaging little guys, one of whom became the central figure in a horror I witnessed. When the puppies reached the age when they started to explore their world, two of them were playing at the edge of the road by the bus stop in front of the campus. I saw them and and I knew what was going to happen. Inevitably one pup wandered into the road, doing puppy things, and was nailed by a Maruti Jeep that didn’t even slow down, whose driver probably didn’t know he’d hit anything.