“GENTLEMEN, I AIN’T A-GOIN”

GUNS OF THE HILLSVILLE COURTHOUSE TRAGEDY

This essay first appeared in the 2013 edition of Gun Digest and received the John T. Amber Literary Award for that year

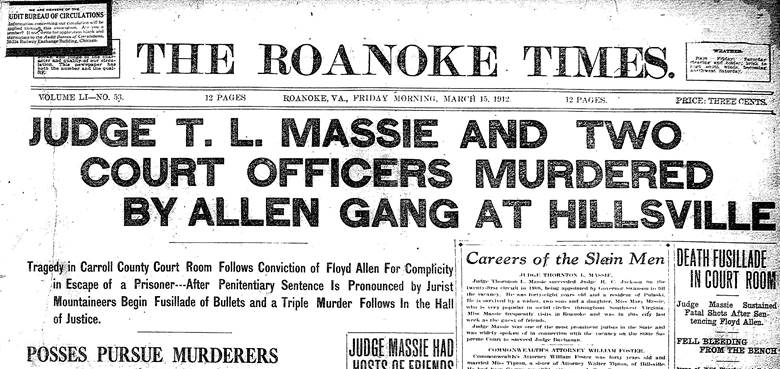

March 14th, 1912, was a cold and dreary day, the sort of early Spring weather typical of southwestern Virginia. At 8:30 that morning, in the Courthouse at Hillsville, the seat of Carroll County, the trial of one Floyd Allen was entering its final day, with the jury having heard arguments from both sides, and about to pronounce sentence on Floyd for “unlawfully rescuing prisoners,” a relatively minor offense. Within minutes of the opening of this third day of the trial, four people would be killed, and several grievously wounded in a hail of bullets, one of whom would die the next day.

Floyd Allen

was a prosperous and well known farmer and landowner, the head of the “Allen

clan.” All the Allens were contemptuous of the law, made no secret of their

contempt, and did whatever they pleased. They were allegedly involved in illicit whiskey manufacture,

counterfeiting, and other offenses; whatever

the truth of these accusations may be, there is no question that many in the

community lived in fear of them, regarding them as a dangerous bunch to mess

with. Floyd Allen was universally

considered the most dangerous of them all. He terrified the people of Carroll

County with his uncontrollable—and uncontrolled—temper and his willingness to

use violence and intimidation to get what he wanted. Many felt that putting him on trial for any

offense was taking a serious risk, and that the authorities should just let

well enough alone. In essence—and with considerable

reason—the Allens believed they were beyond the reach of the law.

Floyd Allen

was a prosperous and well known farmer and landowner, the head of the “Allen

clan.” All the Allens were contemptuous of the law, made no secret of their

contempt, and did whatever they pleased. They were allegedly involved in illicit whiskey manufacture,

counterfeiting, and other offenses; whatever

the truth of these accusations may be, there is no question that many in the

community lived in fear of them, regarding them as a dangerous bunch to mess

with. Floyd Allen was universally

considered the most dangerous of them all. He terrified the people of Carroll

County with his uncontrollable—and uncontrolled—temper and his willingness to

use violence and intimidation to get what he wanted. Many felt that putting him on trial for any

offense was taking a serious risk, and that the authorities should just let

well enough alone. In essence—and with considerable

reason—the Allens believed they were beyond the reach of the law.

Even as a child, Floyd had had a reputation for violent behavior. His mother is known to have had to tie him up from time to time. In 1904 another man bought a piece of land Floyd wanted, thus earning a bullet from the enraged Floyd’s revolver. Floyd was charged with and tried for assault. He wasn’t pleased and let it be known that if convicted he would “kill the judge and jurors,” the probable reason for an extraordinarily lenient sentence: a $100 fine and a symbolic one hour in jail. Even that was too much: with a morbid fear of imprisonment, Floyd swore he would “die and go to Hell” before he’d serve even a minute in a jail cell. Not only did he flatly refuse to serve the nominal sentence, he managed to get it dismissed, and forced the man he’d shot to pay the $100 fine! One authority on the tragedy believes Floyd’s successful evasion of punishment created a background of enmity between him and the court officers that was one of the hidden reasons behind the 1912 trial that erupted into tragedy.

A trivial incident that was the immediate cause for the trial occurred in 1911. Floyd’s nephews Wesley and Sidna Allen had a fight with a third young man outside a church during worship services (as is often the case with young men, this fight was over the favors of a young woman). Wesley and Sidna were arrested, charged with disturbing a church service, tied up by Sheriff’s deputies, and put in a wagon to be brought back to Hillsville to stand trial for this quite minor “crime.” The road passed the home of their Uncle Floyd, who, outraged at the disrespectful treatment of his nephews, enlisted some family help to free the boys from their bonds. Floyd then transported them himself, in a somewhat more dignified manner, to Hillsville where they were sentenced to short jail terms.

Whether or not violence and threats were part of the “rescue” is still a matter of debate: but Floyd’s offense against the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia was great enough to earn him an indictment of his own and a trial. The Commonwealth felt it was time the Allens were brought to heel, and that this incident was the perfect opportunity to do so. After some delay Court proceedings began on March 12th of the following year, 1912.

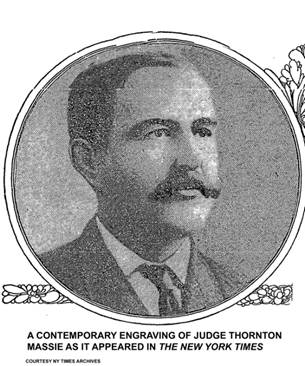

Local historians agree that a couple of weeks before this

trial began, the Commonwealth’s Attorney, William Foster, had received a death

threat from Floyd. Foster showed the letter to the Judge, Thornton Massie, and

asked for extra deputies in the Court, a request the Judge denied as it would

“show cowardice” to do so. There is

evidence the Judge also received a threat, but not only did he refuse the

request for deputies, he refused to arm himself, or to ban spectators from

being armed, as he felt the “majesty of the law” would protect everyone.

Local historians agree that a couple of weeks before this

trial began, the Commonwealth’s Attorney, William Foster, had received a death

threat from Floyd. Foster showed the letter to the Judge, Thornton Massie, and

asked for extra deputies in the Court, a request the Judge denied as it would

“show cowardice” to do so. There is

evidence the Judge also received a threat, but not only did he refuse the

request for deputies, he refused to arm himself, or to ban spectators from

being armed, as he felt the “majesty of the law” would protect everyone.

The jury returned a “guilty” verdict and recommended a sentence of imprisonment for a year and a $1000 fine. A motion to set the verdict aside and free Floyd on bail was denied: as Sheriff Lew Webb started to take the prisoner in hand, Floyd stood up and announced to the world, “Gentlemen, I ain’t a-goin’,” reaching under his sweater for the gun he was carrying. At that point the shooting started.

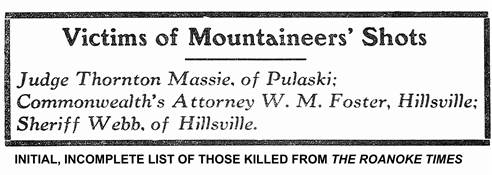

The exact sequence of events, who fired the first shot, and who actually shot whom is a matter of dispute a century later. It is known for certain that at least 57 shots were fired in the Courtroom by numerous participants, including Floyd, his son Claude Allen, Court Clerk Dexter Goad, Commonwealth’s Attorney Foster, and the law officers present. The gun battle lasted only about a minute and a half, moving from the Court into the street outside. When the smoke cleared, Judge Massie, Sheriff Webb, Commonwealth’s Attorney Foster, and a juror, C.C. Fowler, lay dead in the Courtroom: a bystander, Betty Ayers, was mortally wounded and died on the 15th. The Clerk, Dexter Goad, was badly wounded. Floyd was shot in the leg and injured seriously enough that he was unable to escape. The two young men whose fight had started everything escaped with Claude Allen from the immediate vicinity but were later captured after a massive manhunt.

The incident caused a sensation and was headline news all over the country until it was crowded off the front pages by the sinking of the Titanic a month later. Eventually all the fugitives were apprehended and brought to trial: Floyd and Claude Allen were executed and the others all served prison terms. To this day many feel that Floyd and his family were the subjects of political persecution and that the executions amounted to judicial murder. It is beyond the scope of this article to go into the details of the cases for and against the Allens or the echoes of the incident that still reverberate in Carroll County a century later. Numerous books have been written about it for anyone who wants further information: a short bibliography is provided below. My purpose is to discuss the weapons involved in the context of the Virginia of that time. The information given below is taken from Ronald Hall’s book, The Hillsville Courthouse Tragedy. Many details are missing but it’s possible to make educated guesses as to who was armed with what based on this book and surviving pictures of the participants.

In 1912, Virginia—even the rugged and isolated southwestern region—was hardly a frontier society. Nevertheless, many frontier attitudes and traditions persisted: a sense of complete and absolute personal independence, reliance for success solely on self and kin, and contempt for the very concept of government (many residents had fought for the Confederacy or were the children of those who had) were still strong. And far more common then than today was the tradition of going about one’s daily business armed: in the society of 1912 it was a given that any male adult could and would carry a gun. While it is today a felony to enter a Courthouse armed, in 1912 it wasn’t. Judge Massie’s refusal to issue an order disarming everyone in the place is today regarded as hopelessly naïve, but his logic was completely consistent with the spirit of the time and place, and with his regard for the Constitutional rights of citizens. Thus it was that not only spectators but even the defendant came to the Court ready to use force against force; it was unfortunate that Floyd Allen and his relatives were people prepared to do exactly that.

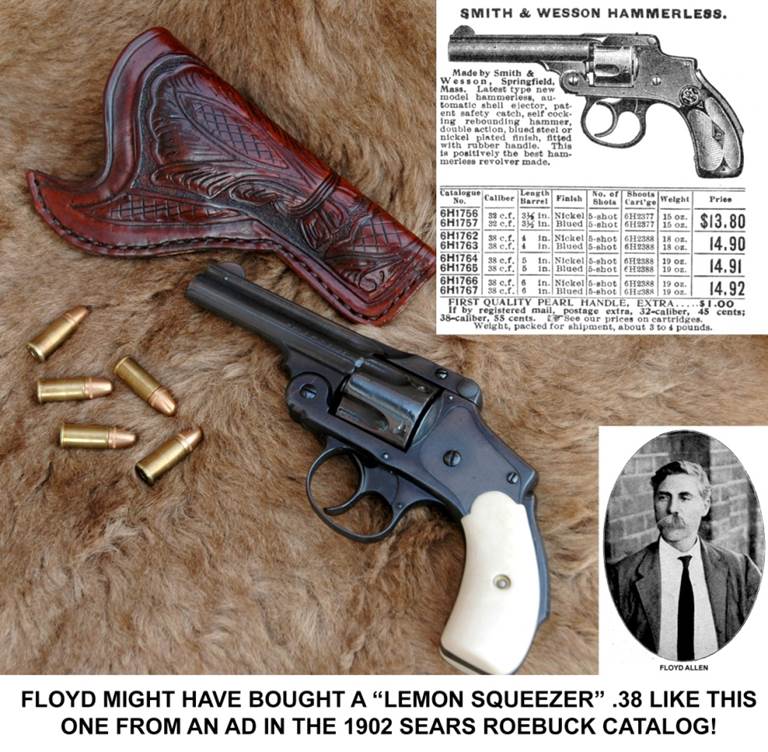

Floyd

was armed with what is described as a “5 shot hammerless .38 Special” but this

is probably a mistake, at least in regard to the caliber. No one in 1912 was manufacturing a hammerless

.38 Special, though several companies did produce hammerless revolvers in the

common .38 S&W caliber. The .38 Special had only been introduced a decade

before; the .38 S&W, dating from 1887, was well suited to small and concealable

revolvers (Floyd’s was under his sweater) and far more common.

Floyd

was armed with what is described as a “5 shot hammerless .38 Special” but this

is probably a mistake, at least in regard to the caliber. No one in 1912 was manufacturing a hammerless

.38 Special, though several companies did produce hammerless revolvers in the

common .38 S&W caliber. The .38 Special had only been introduced a decade

before; the .38 S&W, dating from 1887, was well suited to small and concealable

revolvers (Floyd’s was under his sweater) and far more common.

Most likely Floyd carried a top-break S&W “New Departure” .38, colloquially referred to as “The Lemon Squeezer” from the grip safety in the rear strap. This 5-shot revolver would not fire unless firmly gripped and the safety depressed, a somewhat unusual feature in that era. Top break revolvers had come into widespread use by the 1870’s and found great favor as personal defense weapons. At one time nearly every household in the Commonwealth probably had some sort of top break revolver in a bedside drawer. The “Lemon Squeezer” was one of the best of these, a cash cow for S&W that sold steadily from its introduction in 1889 until production ceased in 1941. The Lemon Squeezer was—and is—an ideal concealed-carry weapon: compact, reliable, easily reloaded, and respectably powerful by the standards of the day. According to contemporary accounts, Floyd had only 4 of the 5 chambers loaded. Leaving an empty chamber under the hammer was a common practice dating from the era of single action revolvers, though the “New Departure” was safe to carry fully loaded, by design.

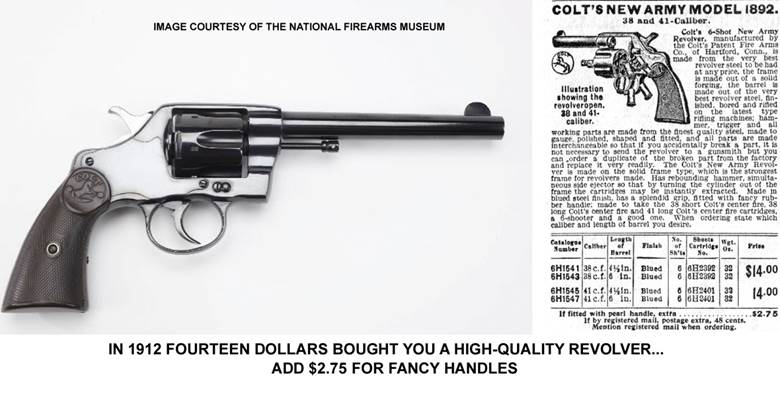

Claude Allen is described as having carried a “Colt .38 Special revolver,” too, and in this case the serial number is known: #63855. This was not, in fact, a .38 Special. The only contemporaneous Colt that carried that serial number was a Model 1892 New Army, chambered in .38 Long Colt, at one time the official issue caliber of the United States Army. It’s very possible, however, that Claude did in fact use .38 Special ammunition in it. Most 1892 New Armies will accept the .38 Special. Despite its case being a bit longer than the .38 Long Colt’s, in all other dimensions the two cases are identical, and the Armies lack the “step” in the chamber that would have prevented the longer case from entering. The .38 Special ammunition of 1912 was probably not powerful enough to create a serious hazard even if Claude was aware of the difference between the two calibers, which he likely wasn’t. He’d have used what was easiest to get.

According to Hall’s account, Claude had left his gun at home on his way to his father’s trial, but it was brought to him at the Courthouse by Victor Allen, Floyd’s other son. Victor was armed too: he was carrying a .32 caliber of unspecified make, most probably another top break, possibly what is sometimes called an “Owl Head.” This would have been an Iver Johnson, whose nickname is derived from the company logo of an owl’s head molded into the gutta-percha grips. The Iver Johnsons were also immensely popular, in large measure because they sold for less than the S&W guns but gave good service. There is dispute about whether Victor actually fired any shots himself, but there’s no doubt he brought Claude the .38 he’d left home.

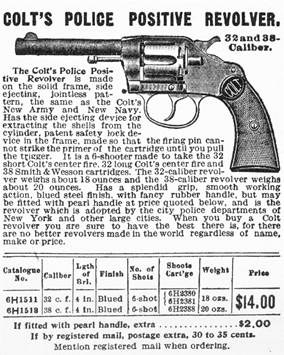

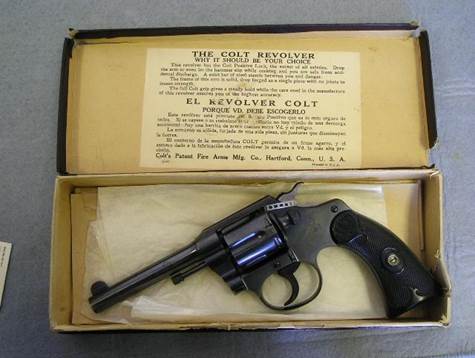

Others in the Court were armed with .38’s, including Deputy Elihu Gillaspie, who probably also had a .38 Lemon Squeezer; and Deputy Frank Fowler, who was armed with a .38 Special with “a six inch barrel.” Fowler’s gun was either a Colt or S&W. A barrel that long would have been very awkward to conceal, and the gun would have been carried openly in a holster, especially if Fowler was on duty. Both Colt and S&W had contracts with police agencies, so if this was Fowler’s issue weapon it would have been either the S&W Model of 1905 (later renamed the “Military & Police”) or Colt’s competing product, the Police Positive Special. Both of these were high-quality guns, the best available in their time. In fact the M&P is one of the most successful revolver designs ever introduced and is still made today.

Although .38 caliber guns were highly favored, not everyone who was armed that day was carrying one. Wesley Edwards—one of the boys who’d been in the fight that started the whole sequence of events—was carrying a .32 revolver, described as a Colt, so it wasn’t a top break because Colt didn’t make those. The most likely candidate is the Colt New Police .32, more or less the same as the Police Positive, but in a lighter caliber. Later, while on the run with his uncle Sidna Allen, the latter described Wesley as armed with an “automatic pistol,” not otherwise specified. Sidna was carrying a .32 revolver and a “repeating shotgun” while on the lam.

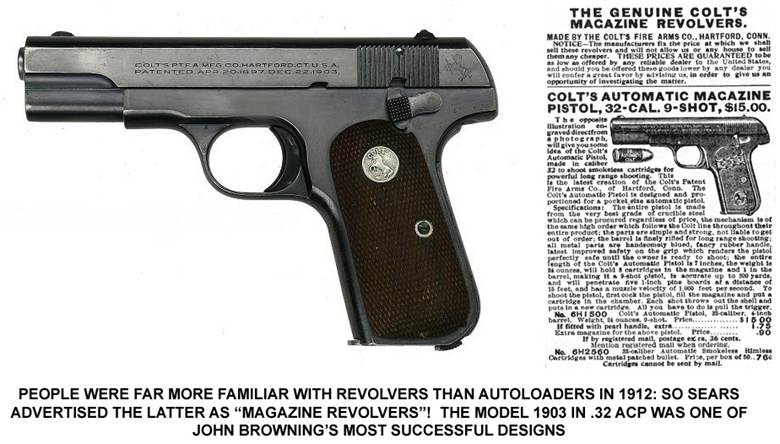

Not everyone used a revolver. Some of the people in the Court were using the newfangled automatic pistols, including Sheriff Lew Webb. His choice of weapon may have got him killed: Webb borrowed a Colt automatic pistol from a relative before going to the courthouse, and didn’t know how to use it. He was carrying a Colt Model 1903, designed by John Browning. The Model 1903 was a slick and easily-concealed gun in .32 ACP caliber with a safety catch on the left side that also serves as a slide lock; and a grip safety.

The Model 1903 is accurate despite its rudimentary sights, but Webb’s unfamiliarity with it may have had fatal consequences. Far more familiar with revolvers, which rarely have any sort of safety catch, he might have fumbled trying to put the safety off. This could easily have taken long enough for him to be shot by one of the Allens. Commonwealth’s Attorney William Foster also carried a Colt .32 Automatic. Presumably he knew how to use it, as the gun belonged to him, but in the end he too was cut down.

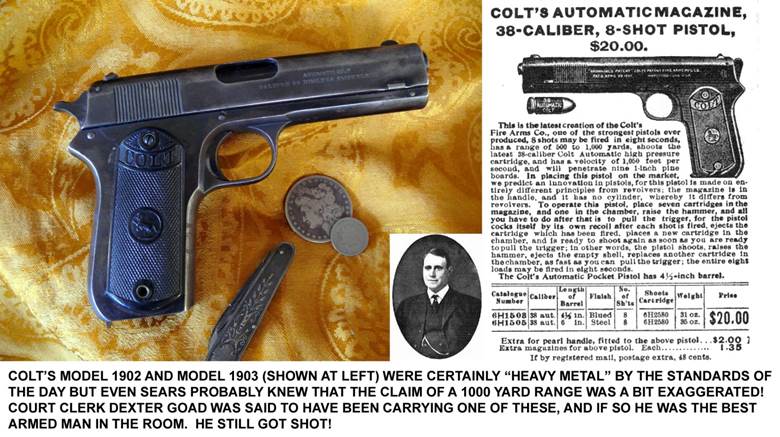

Dexter Goad, Clerk of the Court, was also armed with an automatic pistol, this one described as a “.38 Automatic.” There are two contemporaneous products that meet this description: Colt’s Model of 1902 “Military” pistol and its smaller Model 1903 “Pocket” version, essentially identical except for barrel length. Both were chambered for the then-revolutionary .38 ACP caliber. Presumably Goad was armed with the shorter and more easily concealed Model 1903. The “parallel ruler” locking mechanism used in it is the direct predecessor of that used in the famous Model of 1911 .45. Yet another product of the genius of John Browning, the Model 1903 would have been state of the art in 1912. Goad was very grievously wounded in the shootout but survived.

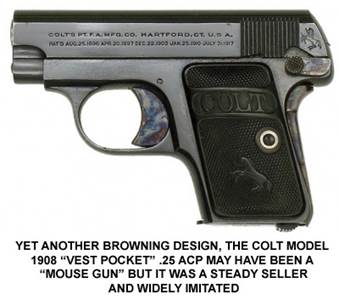

Goad’s Assistant Clerk, Woodson Quesenberry, also carried a

Colt autoloading pistol. It seems that Quesenberry was more interested in

concealment than power, because he was toting a Model 1908 Vest Pocket in .25

ACP. This little popgun—called the “Vest

Pocket” pistol because of its tiny size—was one of Browning’s most successful designs,

widely imitated after its introduction.  Browning had

sold the design to FN in Belgium, but Colt had an exclusive license to

manufacture and sell it in the Americas. Many, many thousands of Model 1908’s were made by both firms up to the

beginning of World War Two: they’re commonly encountered in shops today. The Model 1908 was a sleek seven-shooter with

no sharp edges or protruding parts; and though a decidedly minor contributor to

the carnage, Quesenberry fired it at least once in the course of events.

Browning had

sold the design to FN in Belgium, but Colt had an exclusive license to

manufacture and sell it in the Americas. Many, many thousands of Model 1908’s were made by both firms up to the

beginning of World War Two: they’re commonly encountered in shops today. The Model 1908 was a sleek seven-shooter with

no sharp edges or protruding parts; and though a decidedly minor contributor to

the carnage, Quesenberry fired it at least once in the course of events.

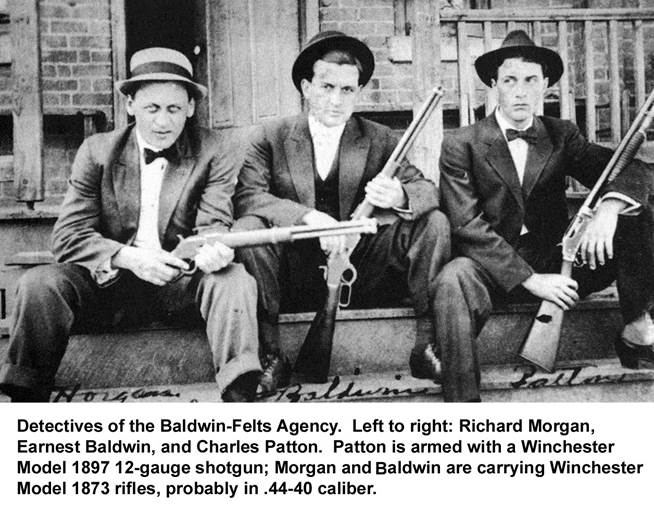

In the aftermath of the shooting, Floyd was captured almost immediately but Claude Allen, Sidna Allen, Wesley Edwards, and Friel Allen fled the scene, triggering a manhunt. The Governor of the Commonwealth, William H. Mann, enlisted the services of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency of Roanoke, and also sent some National Guardsmen to the scene.

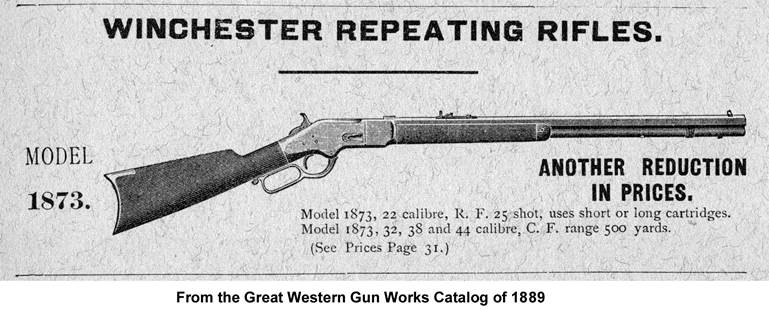

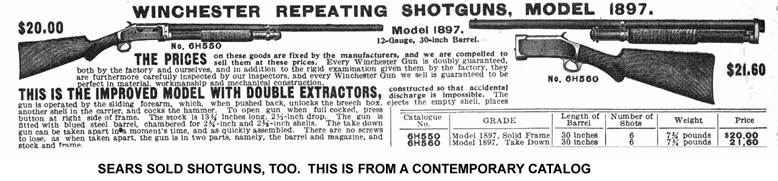

The Baldwin-Felts men were primarily armed with long guns, shown in the many dramatic photos for which they posed. The agency equipped most of its men with a frontier-era firearm, the Winchester Model 1873 rifle, the famous “Gun That Won The West.” The Model 1873 was issued in several calibers and it’s not known what the agency chose, but it most likely was the .44-40, the most powerful round chambered in this rifle. The .44-40 is said to have “...killed more game, large and small, and more men, good and bad, than any other caliber ever made.” This certainly would have been a fine caliber for a manhunt in the brush-covered hills amid the laurels and dogwoods. So would the detectives’ handsome Winchester Model 1897 shotguns.

All in all they were ideally armed for a gunfight at short range—if they had ever managed to get within range of their quarry, which they didn’t.

Friel surrendered quickly, as did Sidna Edwards, saving Baldwin-Felts some trouble: Claude Allen was captured fairly soon, but Wesley Edwards and Sidna Allen led the detectives a merry chase for 5 weeks in the hills and hollows they knew so well. As the Baldwin-Felts men hunted them in cold and wearisome March weather, often sleeping in the rain while staking out an alleged hiding place, the two fugitives received assistance from friends and relatives that enabled them easily to elude the bumbling agents of the law. When the hue and cry died down a bit, Sidna and Wesley simply went to a train station and rode away to work as carpenters in Des Moines, Iowa. They were captured six months later when Wesley wrote to his sweetheart and revealed their location: to this day she is accused by Allen partisans to have “sold” them to the detectives.

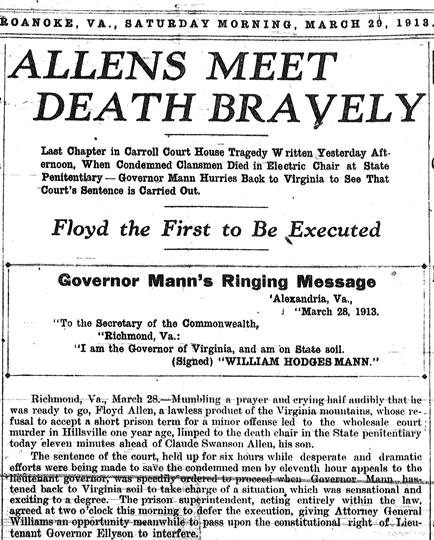

Justice

moved swiftly in those times. In September

of 1912, Floyd and Claude Allen were tried for murder in the Circuit Court in

nearby Wythe County (it was felt that they couldn’t get a fair trial in

Hillsville). Both were duly convicted and sentenced to death. Efforts were made to spare them that fate: in

the intervening year the pair had actually become objects of sympathy in the eyes

of the public. Allegations were made

that they had in fact acted in self-defense (to this day it’s disputed who

fired the first shots) and were being railroaded, victims of a conspiracy by

their political enemies in Carroll County. Petitions to the Governor carrying thousands of signatures were circulated

but rejected. Virginia’s Lieutenant

Governor attempted to finesse the situation with a last minute commutation when

Governor Mann was out of the state; but Governor Mann, on hearing of this,

immediately returned to Commonwealth soil and issued an order to carry out the

sentences. Floyd and Claude died in

Virginia’s electric chair on March 28th, 1913.

Justice

moved swiftly in those times. In September

of 1912, Floyd and Claude Allen were tried for murder in the Circuit Court in

nearby Wythe County (it was felt that they couldn’t get a fair trial in

Hillsville). Both were duly convicted and sentenced to death. Efforts were made to spare them that fate: in

the intervening year the pair had actually become objects of sympathy in the eyes

of the public. Allegations were made

that they had in fact acted in self-defense (to this day it’s disputed who

fired the first shots) and were being railroaded, victims of a conspiracy by

their political enemies in Carroll County. Petitions to the Governor carrying thousands of signatures were circulated

but rejected. Virginia’s Lieutenant

Governor attempted to finesse the situation with a last minute commutation when

Governor Mann was out of the state; but Governor Mann, on hearing of this,

immediately returned to Commonwealth soil and issued an order to carry out the

sentences. Floyd and Claude died in

Virginia’s electric chair on March 28th, 1913.

Modern forensic methods that might have helped sort out the actual sequence of shots and other crucial details were unknown in 1912, so the complete truth of exactly what happened in Hillsville will never be known. But echoes of those long-ago shots still reverberate: a century after the fact debate still rages in Carroll County and other parts of southwestern Virginia as to what really occurred; whether or not the Allens were guilty as charged; and whether they were “judicially murdered” for reasons of political and personal rivalry. The family names of the participants are still common in that part of the world, and descendants on both sides of the divide still argue the case for and against the “Allen clan.” Whether or not the outcome of the trial was true justice can never be known.

But...it’s likely that somewhere in a dusty evidence vault or private collection, the actual guns used still exist, having long outlived those who fired them in anger, despair, or self-defense. They remain—wherever they may be a century later—as mute, inanimate, immortal artifacts forever linked to a tragedy that could perhaps have been avoided, had the living, thinking, flesh-and-blood men involved chosen to try.

Bibliography

Hall, Ronald W. The Carroll County Courthouse Tragedy: A True Account of the Gun battle that Shocked the Nation; Its Causes and the Aftermath. 1998. Carroll County Historical Society (Hillsville).

Lord, W. G. The Red Ear of Corn. 1999. Blue Ridge Institute & Museum (Ferrum).

Virginia Law Register 18 (11):840-842. Claude S. Allen v. Commonwealth and Floyd Allen v. Commonwealth. Richmond, January 15, 1913. [7 Va. App. 271.] 1913.

Credits & Acknowledgments

The Honorable Michael Valentine, Fairfax County Court (Retired)

Mr William G. Lord

Mr Ronald W. Hall

The Roanoke Times Archives

Roanoke Public Library

Woodcuts, Engravings, & Photos

1902 Sears Roebuck Catalog, reprinted by Gun Digest

1889 Great Western Gun Works Catalog, reprinted by Gun Digest

Mr. K. Nasser

The New York Times Archives

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |