THE QUINTESSENTIAL BOY’S RIFLE: HAMILTON’S MODEL 27

This essay first appeared in The Standard Catalog of Firearms

Responsibility, personal discipline, and self-reliance: all these are “manly virtues,” character traits whose importance was fixed in the national psyche by the collective American experience of Colonial times, the Civil War, and westward expansion. (As quaint as such words sound to modern ears, the time when American society expected its youth to develop them is still within living memory.) That collective national experience also fostered a belief in marksmanship and skill at arms as ideal ways to develop and encourage these personal virtues. It was common wisdom throughout the 19th —and most of the 20th—Centuries that providing a boy with a firearm and instruction in how to use it was a normal—in many ways an essential—part of training him to be a responsible adult.

By the late 19th Century, the American firearms industry had seized on this universally accepted notion to develop the special product that today we call “boy’s rifles.” Between roughly 1880 and 1950 this category of guns represented a significant part of the overall market: Savage, Stevens, Remington,

By the late 19th Century, the American firearms industry had seized on this universally accepted notion to develop the special product that today we call “boy’s rifles.” Between roughly 1880 and 1950 this category of guns represented a significant part of the overall market: Savage, Stevens, Remington,

Clarence J. Hamilton and his son Coello weren’t gunsmiths in the traditional sense. Their principal business experience was as manufacturers of sheet-metal products, especially iron-bladed agricultural windmills. They applied their technical knowledge of metal-forming to reduce the costs of making small-caliber rifles, enabling them to enter the field with a competitive edge over companies using traditional methods. They were very successful in this strategy: no one really knows how many Hamilton rifles were made during the firm’s existence, but just one, the Model 27, is known to have been made in numbers well over half a million. Coupled with the large numbers of less-common

Clarence J. Hamilton and his son Coello weren’t gunsmiths in the traditional sense. Their principal business experience was as manufacturers of sheet-metal products, especially iron-bladed agricultural windmills. They applied their technical knowledge of metal-forming to reduce the costs of making small-caliber rifles, enabling them to enter the field with a competitive edge over companies using traditional methods. They were very successful in this strategy: no one really knows how many Hamilton rifles were made during the firm’s existence, but just one, the Model 27, is known to have been made in numbers well over half a million. Coupled with the large numbers of less-common

The Model 27 was introduced in 1907 and production ceased in 1930. It combined major innovations for which the Hamilton Company held patents. The first was the method of making the barrel: by pressure-forming a sheet of metal into a short, thick tube, and then rolling it around a mandrel engraved with a reverse pattern of the rifling. This process was covered under Patent Number 660,725 of October 30, 1900. The

Although

Although

Most “quality” rifles of the day used forged and machined receivers. Again, the

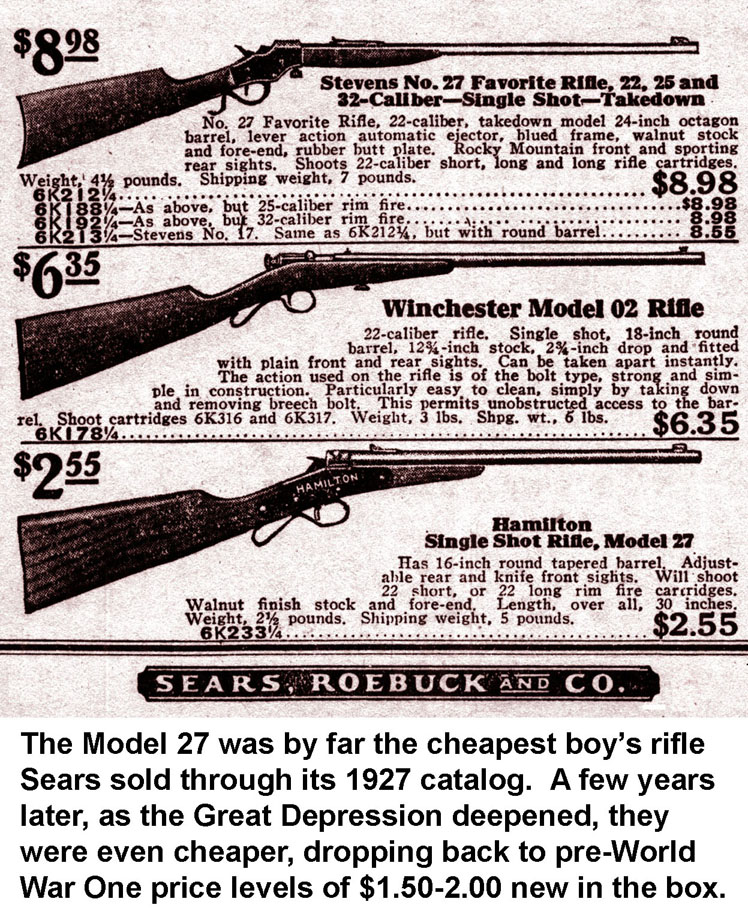

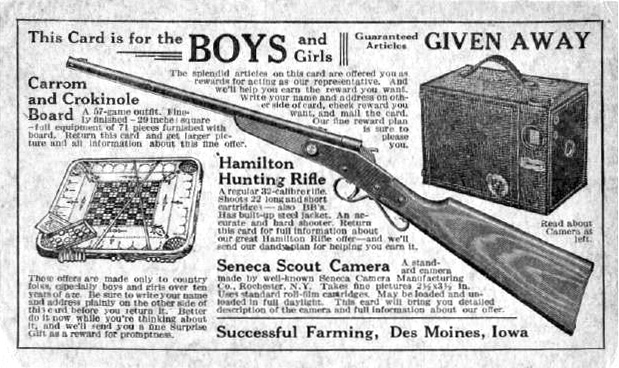

With a couple of pieces of machine-cut wood for a stock and forearm, a spring, and a few standard screws and pins as the remaining parts, Hamilton 27’s could be produced so cheaply that they sold at retail for under $3.00 for most of their production life. Most were sold for far less. In fact, they were often given away as purchase premiums to farmers who bought

With a couple of pieces of machine-cut wood for a stock and forearm, a spring, and a few standard screws and pins as the remaining parts, Hamilton 27’s could be produced so cheaply that they sold at retail for under $3.00 for most of their production life. Most were sold for far less. In fact, they were often given away as purchase premiums to farmers who bought

Mindful that there are always a few customers who have an extra dollar to spare and demand the “best,” Hamilton obliged by producing the Model 027, identical in all respects to the humble Model 27, but featuring a slightly higher grade of wood in the stock and forearm. Some Model 27’s have a plain butt with no buttplate, but some have a sheet metal buttplate tacked in place.

The Model 27 was, in short, the perfect product of its type and for its time. It incorporated innovative design, fast mass production, good quality control, and savvy marketing to serve the public’s need for a safe, reliable, and practical gun for young boys learning to be men.

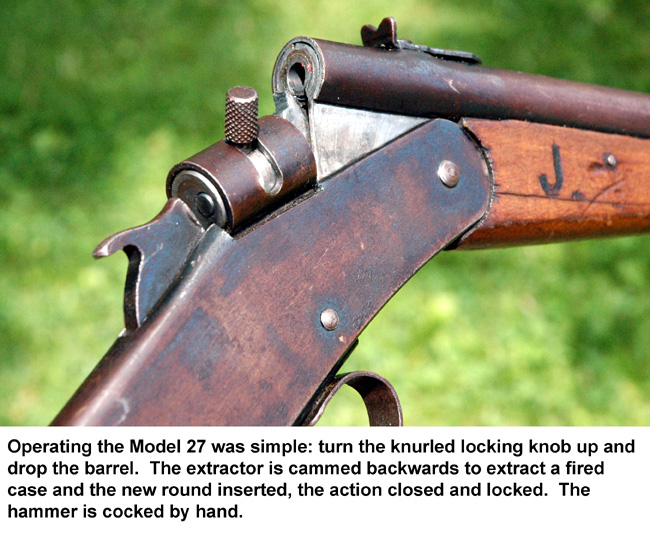

A rifle designed to be inexpensive has to be simple in order to be reliable, and the Model 27 is a wonderful example of simplicity of design, in which every component is functional, as “no frills” as any mechanical object can get. The tip-up action, locked by a rotating drum, has only five moving parts: the locking bolt, trigger, hammer, firing pin and extractor. Mastering its use was the work of a few seconds for any boy, something that isn’t always true of modern products catering to the youth market.

A rifle designed to be inexpensive has to be simple in order to be reliable, and the Model 27 is a wonderful example of simplicity of design, in which every component is functional, as “no frills” as any mechanical object can get. The tip-up action, locked by a rotating drum, has only five moving parts: the locking bolt, trigger, hammer, firing pin and extractor. Mastering its use was the work of a few seconds for any boy, something that isn’t always true of modern products catering to the youth market.

Despite its simple and practical design, the Model 27 has a good deal of visual appeal as well, thanks to its graceful lines and diminutive size. This is perhaps one reason why it was made for so long and sold so well, compared to other

Barrel lengths on Model 27’s vary from just under 15” to 16”. For many years the Model 27 came under the provisions of the  National Firearms Act of 1934 as a “short barreled rifle,” but present day collectors can heave a sigh of relief: in a rare burst of good sense, the BATF eventually decided that the Model 27 does not, after all, represent much of a threat to the peace and stability of the American Republic. All

National Firearms Act of 1934 as a “short barreled rifle,” but present day collectors can heave a sigh of relief: in a rare burst of good sense, the BATF eventually decided that the Model 27 does not, after all, represent much of a threat to the peace and stability of the American Republic. All

Boy’s rifles by their nature led a very hard life, and it’s testimony to the quality of Hamilton’s design and production team that so many Model 27’s still exist, though most of them are pretty beaten up today, worn out and fit only for displays. Very few will have all original parts. The very simple nature of the design encouraged boys to act as their own “gunsmiths” and it’s normal to encounter Model 27’s with hardware-store screws and bolts to replace lost or worn-out ones.

The action is not the most robust design, and after tens of thousands of rounds the barrel pivot and locking block inevitably wear to the point where headspace increases and the gun becomes unsafe. (As a youth I was foolish enough to shoot high-speed Long Rifles in a typically worn Model 27, and dumb enough  not to think about why the rims were blowing out! Yes, I still have two functional eyes, don’t ask me why.)

not to think about why the rims were blowing out! Yes, I still have two functional eyes, don’t ask me why.)

The brass barrels, used with corrosive ammunition (often loaded with black powder as well) are almost always shot out. If there is rifling visible  at all, the barrel is in better shape than average. Many of the barrels will be cracked where corrosion has eaten through the seam left when the barrel was formed around its mandrel. Cracked barrels are unsafe and relegate the rifle to wall-hanger status. The Model 27 was designed to shoot .22 Shorts and Longs, but the relatively low-powered varieties of the time, not what’s on the market now. I would not fire any

at all, the barrel is in better shape than average. Many of the barrels will be cracked where corrosion has eaten through the seam left when the barrel was formed around its mandrel. Cracked barrels are unsafe and relegate the rifle to wall-hanger status. The Model 27 was designed to shoot .22 Shorts and Longs, but the relatively low-powered varieties of the time, not what’s on the market now. I would not fire any

The Hamilton Model 27 is an icon of an era in American life that is, alas, gone forever, washed away by a tidal wave of Political Correctness and anti-gun hysteria. Though most boy’s rifles are still reasonably affordable, their inherent collectors’ interest and the “nostalgia factor” have been driving prices steadily upwards. Prices for Model 27’s have been strong for the past couple of years and have risen significantly for really good examples. A complete and original one in Good condition will bring $300; a really pristine one half again or even twice that (if such a thing even exists outside a museum). As with any other collectible firearm, condition is the main determinant of price: the more original parts that have been replaced, the less it’s worth. Small boys have a strong urge to mark their names with a pocketknife or woodburning kit on everything they own—note that the rifle depicted here has been branded with a “J” by some long-forgotten owner—and such “personalization” detracts from value. An average-quality Model 27 fetches about $150-200; one in comparable condition to the rifle in this article, with a shootable bore, might easily go for twice that figure.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |