Approximately half of the US population can trace its ancestry to the great waves of immigrants who arrived here after the end of the Civil War, the vast majority of them arriving between 1870 and 1920. Most of these people passed through two immigration stations in New York: Ellis Island, opened in 1892 is the better known; but Castle Garden (located at the tip of Manhattan Island) served until that time. Not all immigrants came via New York: many Asians came through San Francisco and not a few Europeans arrived at Baltimore, Boston, Charleston, Savannah, or other east coast ports; some came here via Canada, crossing the border at a time in our history when it was literally possible to walk from one country to another without papers and without hindrance.

I've never been much interested in genealogy: my ancestors came here, after all, to escape from a society in which it mattered who your father was and who his father was, all the way back to Charlemagne (or farther, if possible) and where such things determined the course of your life. But the ease of access to immigration records that has been made possible by the Internet, and most especially access to the fabulous Ellis Island Database triggered my latent curiosity about such things.

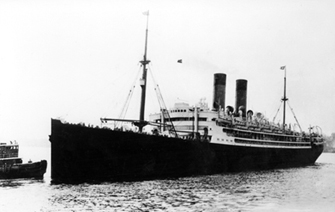

I knew a great deal more about my father's family than my mother's. My father was born here on New Year's Eve 1914, and I knew both his parents during my childhood and adolescence. I grew up on the family stories. One was how Dad's father, after leaving active Italian Army service in 1911, bribed his way out of being recalled from Reserve status for service in the 1912 Tripolitan War, catching the first boat to America he could get. That was the SS Prinzess Irene, of the North German Lloyd Line, a major shipper of human cargo in those days. He landed at Ellis Island on August 24, 1912.

My father's family came from the ancient city of Enna (at the time called "Castrogiovanni") a fortress perched on a hill in the exact center of the island of Sicily. My grandfather Paolo arrived here with a letter of introduction to someone who would employ him as a barber. He had been a manual laborer before his Army service. At the age of 8 he was a "cart boy," pushing a laden cart in a sulfur mine: in other words, he was a beast of burden. A very smart and savvy man, he never did learn to speak English, and carried the scars (literal and figurative)

My father's family came from the ancient city of Enna (at the time called "Castrogiovanni") a fortress perched on a hill in the exact center of the island of Sicily. My grandfather Paolo arrived here with a letter of introduction to someone who would employ him as a barber. He had been a manual laborer before his Army service. At the age of 8 he was a "cart boy," pushing a laden cart in a sulfur mine: in other words, he was a beast of burden. A very smart and savvy man, he never did learn to speak English, and carried the scars (literal and figurative)  of his childhood to the grave.

of his childhood to the grave.

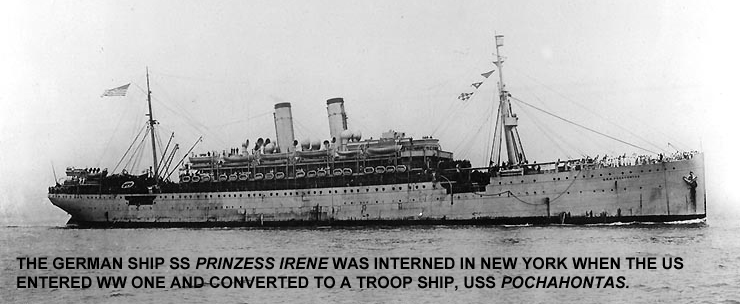

He left behind in Castrogiovanni his fiancee, Letizia Russo. Another family story recounts how Grandpa Paolo lived in the back room of the barber shop, living on hot dogs (at three for a nickel the cheapest thing he could find) to save money to buy her ticket. She arrived on November 6, 1913, aboard the same North German Lloyd ship, SS Prinzess Irene, along with 1494 other passengers. Four years later, when the US entered the First World War, this ship was in New York harbor; as a German vessel she was seized and converted to a troopship, USS Pocahontas.

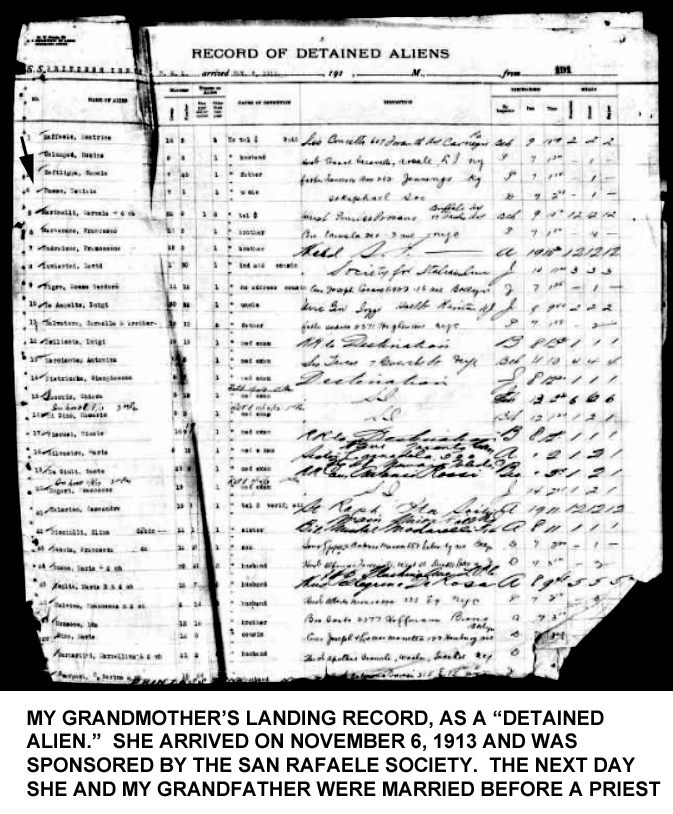

My grandmother's immigration record recorded that she could read. Since her "promised" was not a citizen, he couldn't sponsor her on arrival. She was brought in with the assistance of the "San Rafaele Society,"" an organization dedicated to helping new Italian immigrants get settled, find a job, and get into the mainstream of American society. She is actually listed as a "detained alien," but thanks to the Society she was released quickly.

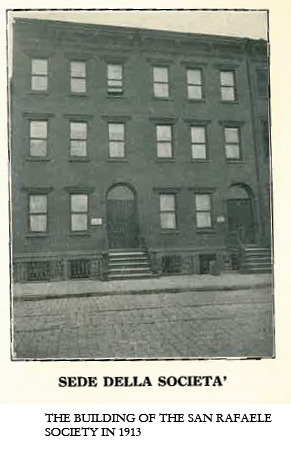

Although she and my grandfather had been betrothed in Sicily, quite correctly my grandmother refused to enter the New World with a man to whom she wasn't properly married—which meant in front of a priest. Conveniently, the San Rafaele Society made arrangements for this. I contacted the Center for Migration Studies in New York and got a great deal of information about this organization.

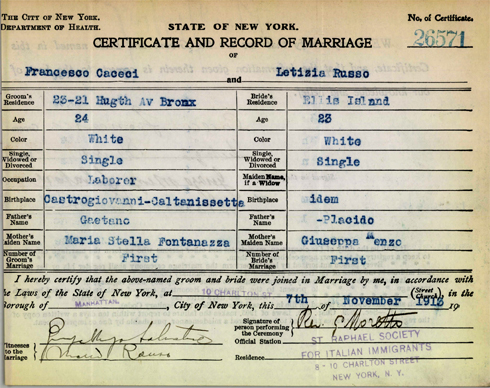

The two were joined in matrimony on November 7, 1913: as soon as she was released from detention. According to what I found out their marriage was recorded as having taken place at Our Lady of Pompeii Church, but Ms Mary Brown at CMS said:

You may want to ask someone who works more regularly with marriage records, but my bet is the marriage was recorded at Pompei and performed at the St. Raphael Society. St. Raphael wasn't a parish and could perform weddings only because it was delegated to do so by a parish, in this case, Pompei. The clincher detail would be the name of the celebrant at the marriage. Father Gaspare Moretto was the Director of the Saint Raphael Society and performed the marriages there. Any other name and the wedding probably would have been at Pompei itself.

I don't have any photos of the chapel at the Saint Raphael Society, but I think I sent you an annual report with a photo of the exterior. The building was demolished in 1927 to make way for a widened Sixth Avenue. Just in case the marriage was at Pompei, attached please find photos of the church at the time. The parish was then at 210 Bleecker Street, in an 1830s Greek Revival building that was also demolished in the widening of Sixth Avenue. Also attached please find a photo of some of Pompei's clergy at the time. Father Moretto is the one holding the camera bulb; the others served at Pompei itself.

The New York City Department of Vital Records had a facsimile of the marriage certificate on file: the celebrant was indeed Father Moretto, shown above, so the ceremony took place at the Society building. The wonders of the Internet! Father Moretto is holding the camera bulb.

One very odd thing is that the groom's name is given as "Francesco Caceci," but my grandfather was "Paolo" as far as I always knew. Later records including his naturalization certificate and WW One draft card give his name as "Paul." I'm not sure how this error crept into the record, if it is an error. It's unquestionably odd: everything else I got from a database of Roman Catholic marriages is correct with regard to date, my grandmother's name, and the location. I suppose it's possible my paternal grandfather had a first and middle name, but if so, I never knew it. I obtained his birth record from Sicily and indeed he was christened as "Francesco." I can perhaps someday clear this up, but there is no doubt whatever about the marriage between Francesco and Letizia here in America.

A few years back I was in Sicily on business and naturally felt compelled to seek out some of my "roots." The elderly gentleman in the image may be my great-grandfather, whose name was Gaetano (and after whom my father was named). I not sure who the woman is: my father told me it wasn't a daughter but recently I received from a cousin a scan of a picture of what may be the same woman at an older age. On the back is inscribed "From your affectionate sister Maria." I also had a scan of an airmail envelope with the return address of a "Maria Caceci, Vicolo Maltisotto, 27, Enna." I don't know when the picture above was made, but I suspect sometime around the First World War. The picture was certainly made before transatlantic air mail was possible, so there's a pretty good chance the young woman and the older one are the same person. A maiden aunt? She would be my great aunt Maria if she's who I think she is.

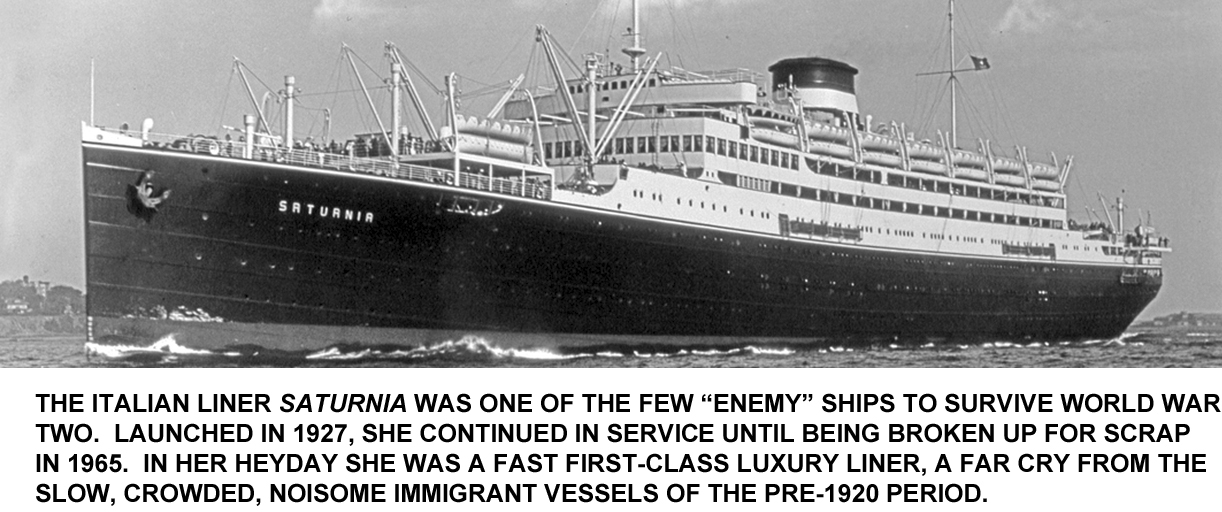

My father, who was in his 90's when I went to Sicily, had visited his father's family as a 14-year-old boy in June of 1929. The entire family, consisting of my father, his two younger brothers Giovanni and Amerigo, and of course my grandmother, made the trip both ways in the near-new Italian Line ship Saturnia.

She'd been launched in 1927 and although they traveled "Second Cabin," I'm sure they found the journey far more comfortable than a crossing in one of the NGL pig-boats must have been. Naturally I asked my father if he remembered the name of the street where his grandfather had lived in Enna, and amazingly, after 80 years, he did: Vicolo Maltisotto.

A "vicolo" is a dead-end alley, a place of as minor street-ness as it's possible for a street to be. By sheer dumb luck, I actually found this minuscule corner of an obscure city in an unimportant province of a bush-league nation...and on the corner of the Vicolo Maltisotto and Via Roma (there is a Via Roma in every Italian city and town) I found a man with exactly the same name as my father! Walking around I saw a lot of people I know I'm related to, as well.

On my return I showed my father the picture above left, and asked which door had been his father's home. He said "The one at the bottom of the stairs," so the red door is the Wellspring of my family, and it still seems to be seeping. Incidentally, what is shown here is the entire length and breadth of Viccolo Maltisotto. The Outdoorsman comes from humble origins, to be sure.

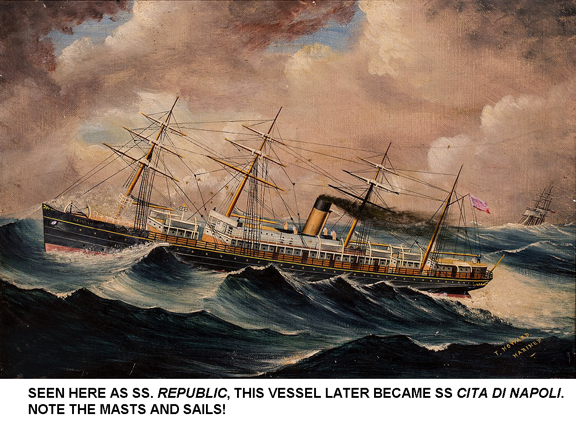

My mother's family story is a little more complicated, but it too is a classic immigrant tale. Her mother's side came from east of Palermo. My maternal grandmother's maiden name was Carolina Perdicaro (at right). On December 23rd, 1903, her father, Giovanni Perdicaro (age 43, married) and her grandfather, Carlo Perdicaro (age 65, widowed) landed at Ellis Island. On arrival, the records indicate that Giovanni Perdicaro and his wife Rosaria's Carolina was about 12. Rosaria and Carolina had come over on August 26, 1903, aboard the Citta Di Napoli. That ship had been built in 1871 for the British White Star Line as SS Republic, then had passed through a series of ownership and name changes. By 1903 she was a worn-out tub ready for the scrap yard; she was eventually scrapped in 1910.

My mother's family story is a little more complicated, but it too is a classic immigrant tale. Her mother's side came from east of Palermo. My maternal grandmother's maiden name was Carolina Perdicaro (at right). On December 23rd, 1903, her father, Giovanni Perdicaro (age 43, married) and her grandfather, Carlo Perdicaro (age 65, widowed) landed at Ellis Island. On arrival, the records indicate that Giovanni Perdicaro and his wife Rosaria's Carolina was about 12. Rosaria and Carolina had come over on August 26, 1903, aboard the Citta Di Napoli. That ship had been built in 1871 for the British White Star Line as SS Republic, then had passed through a series of ownership and name changes. By 1903 she was a worn-out tub ready for the scrap yard; she was eventually scrapped in 1910.

When he landed, Giovanni—my great-grandfather—had $110 in his pocket, a considerable sum of money in those days: he was a reputable and prosperous merchant, a goldsmith, in fact. His father Carlo—my great-great-grandfather—arrived with $30, so that neither of them had to hang their head as they stepped off the boat. Both were sponsored by Giovanni's brother, Giuseppe Perdicaro, of New York City. Giuseppe lived on East 51st Street in Manhattan, where I believe he had his goldsmith's shop.

When he landed, Giovanni—my great-grandfather—had $110 in his pocket, a considerable sum of money in those days: he was a reputable and prosperous merchant, a goldsmith, in fact. His father Carlo—my great-great-grandfather—arrived with $30, so that neither of them had to hang their head as they stepped off the boat. Both were sponsored by Giovanni's brother, Giuseppe Perdicaro, of New York City. Giuseppe lived on East 51st Street in Manhattan, where I believe he had his goldsmith's shop.

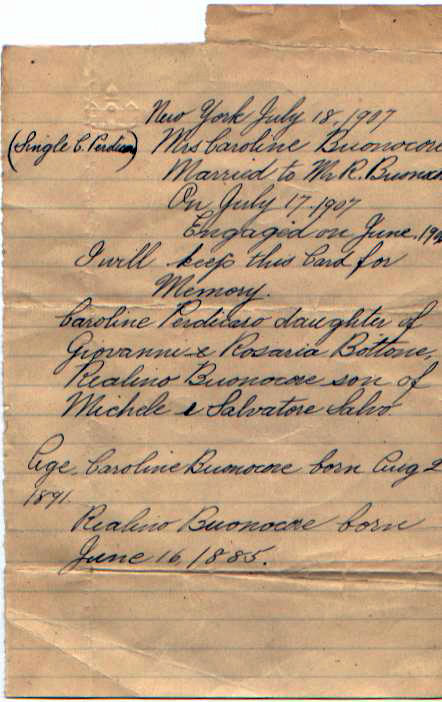

At some point Giovanni took into his business a young assistant/apprentice, one Realino Buonocore (left) who was born in 1885 in Sant' Agata di Militello, in Messina Province, a pleasant seaside community that today is a resort city. His parents were Michael and Salvatore Buonocore, my great-grandparents. Realino Buonocore, my maternal grandfather, came to the USA aboard SS California, on June 26, 1903. I never knew him: he died at age 34 on February 19, 1920, of heart failure during a medical procedure. My great-grandmother Buonocore (nee Salvo), lived a remarkably long life: she was born (in the "Kingdom of the Two Sicilies," as it was then called) sometime between 1859 and 1861 (well before the creation of the Italian Republic, and just before or during the Presidency of Abraham Lincoln). She died, an American citizen, in 1964 as Lyndon Johnson was beginning the escalation of the war in Vietnam.

Grandpa Buonocore assured his success in the jewelry business not only by his skill (I have seen things he made) but by the time-honored  method of marrying the boss's daughter (who was a month shy of being 17, which in Italian families at that time meant she was approaching "Old Maid" status and had better close the deal). That was in 1907. Among my late mother's papers I found the document at left, a note of the marriage. My niece Caroline, who is named for her great grandmother, has her original marriage license. My Grandma Buonocore had seven children of whom six survived childhood, including my mother, who was born in 1918. Grandma Buonocore was naturalized in the New York County Supreme Naturalization Court on June 8, 1921, a year and a half after she was widowed.

method of marrying the boss's daughter (who was a month shy of being 17, which in Italian families at that time meant she was approaching "Old Maid" status and had better close the deal). That was in 1907. Among my late mother's papers I found the document at left, a note of the marriage. My niece Caroline, who is named for her great grandmother, has her original marriage license. My Grandma Buonocore had seven children of whom six survived childhood, including my mother, who was born in 1918. Grandma Buonocore was naturalized in the New York County Supreme Naturalization Court on June 8, 1921, a year and a half after she was widowed.

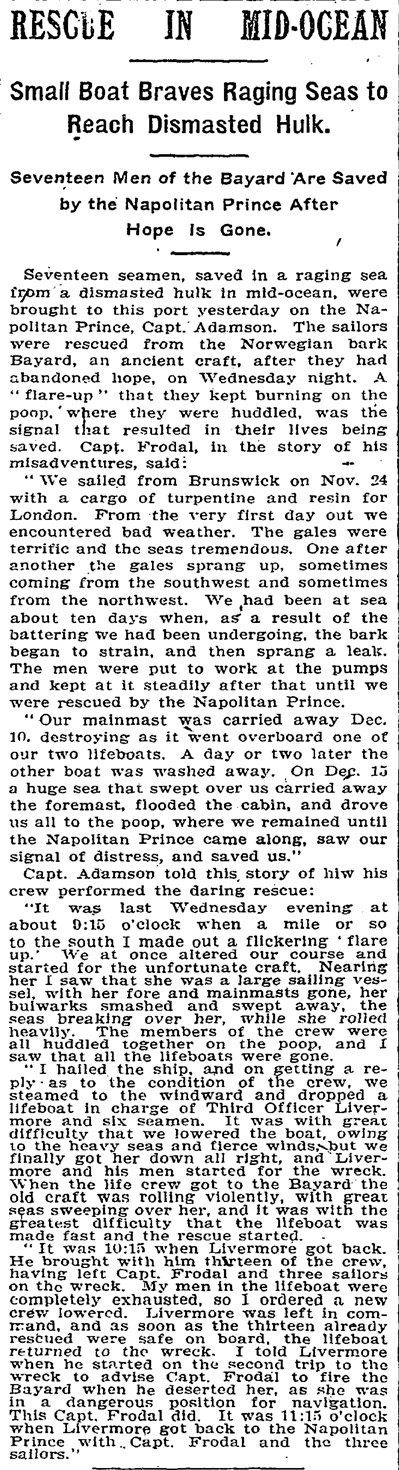

I've referred to the ease with which records of long-dead events can now be found, and will complete this tale with another illustration of the sort of astonishing power of the Internet to bring the past back. This is the incident that occurred during the voyage my Perdicaro ancestors made in 1903.

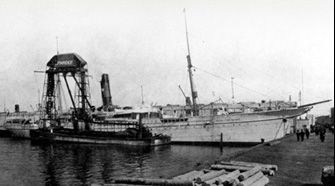

Not only is there information on the men but on the ship in which they sailed: she was Napolitan Prince, built in 1889 as an order for the Portuguese Government. Constructed at Scott's Shipyard in Greenock, Scotland, she was originally named Rei de Portugal. She was acquired in 1902 by the Prince Line, one of the less well known companies that made a fortune carrying immigrants to America before the Golden Door was slammed shut by quotas in 1920. Prince Line re-named her Napolitan Prince, and ran her for 9 years on the Mediterranean-New York run. Worn out by service in the Atlantic, she  was re-sold in 1911 and renamed Manouf, plying the calmer waters between Marseilles and North African ports until 1929, when she was scrapped. She's shown here in the photo. She grossed 2900 tons, which means she wasn't much of a ship; that's about a third the gross tonnage of a modern "DDG," the Navy's term for a missile-armed destroyer. Napolitan Prince was 363 feet long and 42 feet of beam, and could steam at 12 knots (about 15 miles per hour). Note the two masts, one funnel, and a bowsprit! These were the days of "suspenders-and-belt" sailors, and this ship could presumably use sails on nice days—in the North Atlantic in December there aren't many of those. But in the 1880's that's the way marine architects thought, and since immigrants paid fares and coal didn't, they skimped on coal when they could.

was re-sold in 1911 and renamed Manouf, plying the calmer waters between Marseilles and North African ports until 1929, when she was scrapped. She's shown here in the photo. She grossed 2900 tons, which means she wasn't much of a ship; that's about a third the gross tonnage of a modern "DDG," the Navy's term for a missile-armed destroyer. Napolitan Prince was 363 feet long and 42 feet of beam, and could steam at 12 knots (about 15 miles per hour). Note the two masts, one funnel, and a bowsprit! These were the days of "suspenders-and-belt" sailors, and this ship could presumably use sails on nice days—in the North Atlantic in December there aren't many of those. But in the 1880's that's the way marine architects thought, and since immigrants paid fares and coal didn't, they skimped on coal when they could.

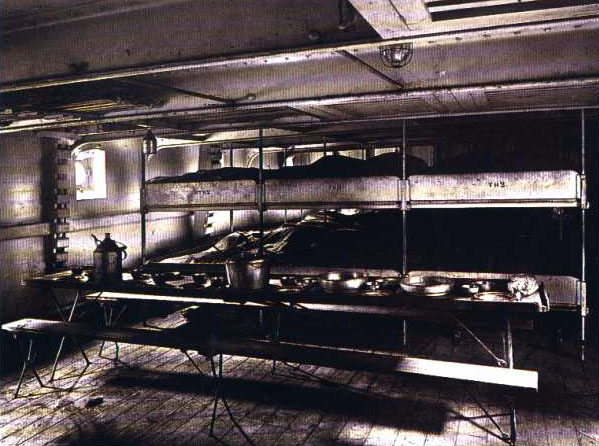

Imagine how long it took to cross the North Atlantic in December in such a ship; and imagine, if you can, what discomfort it entailed. Napolitan Prince carried 1175 passengers of whom 1150 traveled "Third Class," i.e., they were crammed into this little vessel like cattle. They spent anywhere from three weeks to a month—maybe more, depending on winds, and weather—stacked up on multi-tiered bunks, dealing with seasick babies (and adults) and eating whatever slop the steamship line could get away with serving them. With more than 1100 people crammed into steerage, I doubt they had to heat the "living" quarters much, even in December. Nowadays in Messina harbor you will see huge commercial cruise ships at the docks: easily three times as long, and with about 15 times the tonnage.  Napolitan Prince embarked immigrant passengers at Palermo, Genoa, and Naples. The ones who boarded first, in Palermo, would have had an additional week of misery before setting out across the Pond for a new life.

Napolitan Prince embarked immigrant passengers at Palermo, Genoa, and Naples. The ones who boarded first, in Palermo, would have had an additional week of misery before setting out across the Pond for a new life.

There is one more piece of the story: halfway across the Atlantic, Napolitan Prince rescued 17 men from the dismasted vessel Bayard in a raging December storm. This was no mean feat of seamanship on the Captain's part. Jockeying a 2900-ton vessel in a furious North Atlantic gale takes skill and daring, and apparently the rescue effort saved the lives of the entire Bayard crew. It was indeed a heroic feat, which was duly reported in the NY Times on the day my ancestors landed: I imagine great and great-great grandfathers told the story of that rescue for the rest of their lives as well they should have.

It's probably beyond the ability of present-day Americans who are descended from the people who lived through these events to really comprehend what their world was like, and what levels of desperation they had reached to be willing to take such chances to improve the lives of their children and grandchildren. Many immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were, like my mother's family, middle-class people; but most, like my father's were the "wretched refuse" of whom Emma Lazarus' immortal poem at the base of the Statue of Liberty speaks.

We argue endlessly today about immigration, discussing the porous border with Mexico (how come no one ever complains about the even-more-porous border with Canada, I wonder?) and the potential threat to our society such a situation presents. It is worth noting that when my ancestors came here, all the vitriol and discrimination that today are directed at immigrants from Central America and Asia were aimed squarely at them. A little perusal of newspaper stories and magazines of the period before 1920 will reveal this clearly: if you substitute "Italians" and "Jews" and "Poles" for "Mexicans" and "Koreans" the pieces could have come off the pages of yesterday's newspapers. Instead of "Wetbacks," "Greasers" and "Slopeheads" the direct ancestors of half of America's current "native" population were Kikes, Polacks, Dagos, Guineas, Wops, Bohunks, and so forth. They were going to "destroy the American way of life" and they were a "source of crime" and "refusing to become a part of America." Of course, none of that happened, and it isn't going to happen today. Just as my illiterate peasant grandfather sent his three sons through professional school, conferring on his adopted land a series of physicians, dentists, and professors who have long since made great return on his (and the country's) "investment" in him, so will today's fruit pickers and gardeners and tienda owners bear children who will be "100% Americans" who will, in their turn, probably hate the next wave of immigrants from somewhere else.

Not all immigrants came here with the intention of staying permanently. Many intended to return home after having "made a pile" that would enable them to live in comfort in the Old Country.

Not all immigrants came here with the intention of staying permanently. Many intended to return home after having "made a pile" that would enable them to live in comfort in the Old Country.

My paternal grandfather Paolo was naturalized as a US citizen in February of 1925, probably as early as he could legally manage it. But his wife, I discovered, didn't apply for naturalization until 1942, by which time she'd been here nearly 40 years. I have to believe she was one who wanted to go "home" someday, though she never did; and I think that since the US was at war with Italy in 1942, perhaps one reason she applied was the fact that technically, as an Italian citizen, she was an "enemy alien." The idea that a woman in her 50's (with early-stage Parkinson's Disease, yet) could represent a threat to the American Republic might seem comical today, but many US citizens of Japanese origin—some actually born here—were considered a threat and interned in the Spring of that year. So my paternal grandmother applied for naturalization on September 12, 1942 (a few months after the internment order went into  effect on the West coast); her petition was granted on December 12, 1943 and she took the oath of allegiance. By the time she became a citizen, Italy had surrendered, changed sides and was a US ally!

effect on the West coast); her petition was granted on December 12, 1943 and she took the oath of allegiance. By the time she became a citizen, Italy had surrendered, changed sides and was a US ally!

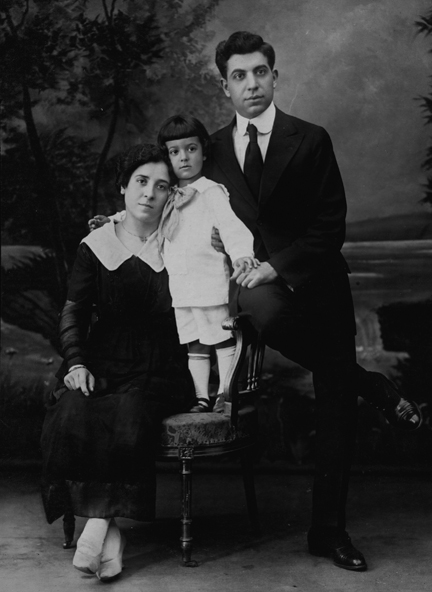

The formal studio portrait at right was taken in about 1918 or 1919. The little boy is my father, who was 4 or 5 at the time. He once told me a story from that 1929 trip: my grandfather Paolo had made several killings in the 20's in the stock market (illiterate he may have been—my father read the daily stock market quotations to him—but stupid he wasn't) and was an enormously wealthy man by his lights. His parents and relatives in Enna begged him to stay, to buy a home and retire on his money to live like a king. "No," he replied, "America is my country now."

He and many others made that choice and it was the right one. Immigration has always been good for the United States: all of us, more or less, are descendants of immigrants, even "Native" Americans, whose ancestors immigrated from Asia by land in Pleistocene times. After my own somewhat aggravating trip to Sicily (a rather chaotic land of lotus-eaters by American standards, but they seem to enjoy life) I remarked to my father that I thought maybe all the ones with energy and drive had, like his father left. He agreed, and thanked God and his father for having done so.

So do I.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |