COLT OR REMINGTON: WHICH IS BETTER?

Replica black powder revolvers are a significant part of the sport shooting market. Sales of these guns began in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, when some far-sighted companies realized the interest in old weapons generated by the American Civil War Centennial. Surviving original guns were too old, too abused, or too valuable to shoot, but Italian-made replicas duplicated the feel, mystique, and romance of the period of the war and the post-war expansion of the western frontier. Replicas remained viable products long after the Centennial ended, and today are more popular than ever. Far, far, more percussion revolvers have been made by a few firms in and near Brescia than were made by all the original manufacturers, combined. Sam Colt could only have dreamed of the sorts of sales figures the two main producers, Uberti and Pietta, have achieved. Today’s replicas are products Sam would have envied for their quality, finish, and low retail price.

Replicas of all the best-known models have been made, by far the great majority of which fall into two categories: “Colt-style” and “Remington-style” guns. Both these basic designs have good and bad features from the user’s point of view. This article discusses them in general terms, and studiously ignores less common models such as the LeMat, Starr, and single-shot percussion pistols. The principal difference between the two designs lies in the frame and how the barrel is held to it.

Colt-style guns have an “open top” frame, that is, one with no top strap over the cylinder. A cross wedge is used to hold the barrel assembly to a long, stout axis pin that protrudes far enough from the frame to extend beyond the cylinder. This design is used in nearly all the Colt percussion revolvers, and it’s typified by the Model 1860 Army, the Model 1851 Navy, and various smaller guns in .31 and .36 caliber. (One exception is the solid-frame Root replica, not often encountered.)

The wedge is a vital component, so it’s held into its slot in the barrel by a screw that prevents it from falling out. Breakdown is achieved by knocking the wedge loose, and pulling the barrel forward, leaving you with three main pieces: the barrel assembly, the cylinder (which slides off the axis pin), and the frame containing the firing mechanism. Reassembly is in reverse order.

The wedge is a vital component, so it’s held into its slot in the barrel by a screw that prevents it from falling out. Breakdown is achieved by knocking the wedge loose, and pulling the barrel forward, leaving you with three main pieces: the barrel assembly, the cylinder (which slides off the axis pin), and the frame containing the firing mechanism. Reassembly is in reverse order.

Remington-style guns have a closed or “solid” frame: there is a top strap over the cylinder and the barrel is screwed into the front frame riser. Dismounting a Remington is performed by dropping the rammer lever, and pulling the thin axis pin forward. The axis pin is captive and won’t come out of the frame, but it comes forward far enough to allow the cylinder to be “rolled” out of the frame

Remington-style guns have a closed or “solid” frame: there is a top strap over the cylinder and the barrel is screwed into the front frame riser. Dismounting a Remington is performed by dropping the rammer lever, and pulling the thin axis pin forward. The axis pin is captive and won’t come out of the frame, but it comes forward far enough to allow the cylinder to be “rolled” out of the frame  opening. Thus you end up with two main pieces after disassembly: the frame/barrel combination and the cylinder.

opening. Thus you end up with two main pieces after disassembly: the frame/barrel combination and the cylinder.

At first glance, the Remingtons would appear to have the better design, but there are in fact some reasons why Colts were successful competitors and actually sold in greater numbers. I’d like to discuss these in turn below, and give my observations based on 40 years’ experience shooting both types.

STENGTH

It’s often said that Remingtons are stronger than Colts, by virtue of the top strap. This may be true, but in the context of percussion revolvers and their actual use, it’s probably unimportant. Normal black powder charges don’t produce anywhere near the pressures that smokeless does. The Remington may indeed be stronger, but the Colt is more than adequate to handle black powder.

I once owned a Colt Navy that did something very odd, but taught me something about the inherent nature of percussion ignition. Every time it was fired the cylinder would turn partially and the hammer would stop between two chambers. There was nothing wrong with the timing or the internal parts, and I was using normal charges: this behavior was traced to too-large flash channels in the nipples. New nipples with smaller flash channels solved the problem completely.

Percussion revolver chambers are only momentarily sealed, by the inertia of the hammer and deformation of the soft copper cap. An overly large flash channel will allow even normal chamber pressure to be exerted over too large an area of the hammer face, so that the total force exerted becomes great enough to overcome the mainspring’s tension and the hammer’s inertia. When this happens, even though chamber pressures are normal, the hammer can be shoved part way back, sometimes even to the half-cock position, partially rotating the cylinder.

Thus, percussion revolvers have a built in “safety valve,” and the first sign of overpressure is a tendency for hammer blow-back. Before pressure can get high enough to blow out the cylinder wall, the un-sealed chamber will prevent it from happening1 and give you some warning to back off.

It’s virtually impossible to destroy a steel-framed version of either design using black powder or a substitute. A typical .44 percussion replica will hold at most 35 grains of FFg and still have room for the bullet, nowhere near enough to cause catastrophic damage.

Since finer granulation black powder burns faster, using FFFFg instead of FFFg and constant, frequent use of maximum charges of very fine grained powder might eventually cause a gun to go out of time and/or shoot loose, the fact is that you simply can’t get enough powder into the chamber to blow the gun up unless it’s in really poor condition from neglect and deterioration. Long before such an event could happen, there would be warning signs such as hammer blow-back.

I think, therefore, that the strength argument can be dismissed as irrelevant. Both designs are adequate to contain normal pressures is the gun is in proper condition.

ACCURACY

There are so many variables involved in this it’s impossible to decide which is the better system, but in theory the advantage has to go to the Remington, thanks to its solid frame. However, one of my Colt replicas will consistently shoot under 2” off sandbags at 25 yards, so the open top doesn’t mean Colts are inherently less accurate because they lack a top strap.

Thanks to the top strap, though, the Remington has the advantage of having better sights. Even the fixed groove in the top strap is preferable to the crude notch in the hammer tip that’s all the Colt can boast in the way of a rear sight; and while it’s impossible to fit a Colt with adjustable sights at all, these are found on some Remington variants. The Remington is the clear preference of those who shoot black powder revolvers in bull’s-eye competition.

Adjustable sights are rarely, if ever, seen on original guns, and for good reason: they weren’t needed. Considering the use to which the originals were intended to be put—close range fighting—the presumptively better accuracy of the Remington isn’t all that important. Percussion revolvers aren’t target guns, nor are they intended for shooting small game. They were designed to be used on humans at typical gunfight ranges of 7 yards. Either will achieve hits under these conditions.

RAPID RELOADS

Cowboy Action shooters may have a different opinion, but in my experience neither design qualifies as “fast” in action. Both are inherently slow to reload using loose powder and ball, and the “speed loading” technique sometimes advocated—using a pre-charged spare cylinder—is a cumbersome process with either design.

The legend is often repeated that in The Wild West, rapid reloads were achieved by using a spare, pre-charged cylinder. I doubt this was ever done in real life, however often it may be done in Cowboy Action shooting. For one thing, percussion revolvers were usually sold in cased sets with accessories: while a set might well have contained a spare cylinder, it would have been a costly option, best suited to a gun dedicated to light duty and pure sporting use, not personal defense and daily carry. A spare cylinder certainly wasn’t included as an accessory for workaday guns sold to the Army; and to people moving westward it would have been a small and expensive item that was easily lost.

Furthermore, fitting a spare cylinder to a gun requires a gunsmith’s services. An Army post might have had an armorer who could do the job, but skilled gunsmiths were pretty thin on the ground west of

Furthermore, fitting a spare cylinder to a gun requires a gunsmith’s services. An Army post might have had an armorer who could do the job, but skilled gunsmiths were pretty thin on the ground west of

Even more unlikely, occasionally you’ll read that this sort of “speed loading” was carried out on a running horse: all I can say to that is, “Hooey.” Anyone running for his life from a band of Apaches or banditos would be absolutely, positively, 100% guaranteed to drop something if he tried to swap out cylinders on horseback. Two hands are required, and three wouldn’t be too many, because if you’re using two to change the cylinder, you have left none for controlling the galloping horse. There are too many bits that can be dropped and lost in the process. A man intent on preserving his hair would have been far better off with a second gun.

Assuming one did go the spare cylinder route, swapping them out is somewhat easier in a Remington; and there are fewer parts to lose. Once you learn The Secret Remington Handshake needed to get the old cylinder out and a new one in, it can be done reasonably quickly if you aren’t being shot at. It’s quicker than doing it with a Colt, which demands a process of field-strip and re-assembly. This is one reason why Remingtons seem to be more popular in the Cowboy Action shooting games, where you’re racing against a clock, not a horde of indignant Redskins who want your hair for a trophy.

There’s also a major safety issue involved in a cylinder swap. A loaded, capped cylinder is essentially a small pepperbox revolver all by itself. If it’s bouncing around in a pocket or saddlebag, and something bonks a cap…BANG, you get a bullet in your leg or in your horse. You wouldn’t appreciate this, and neither would your horse.

SAFETY IN HANDLING

Percussion revolvers usually lack the safety refinements found in modern guns, such as rebound mechanisms, safety catches or transfer bars. Handling them safely requires constant attention.

The lack of a rebound position is especially serious. When the hammer is lowered, it comes to rest in the fully forward position, i.e., resting firmly on whatever is underneath it. If what's underneath it is a percussion cap, a blow to the hammer spur will set the gun off. This is a very real and dangerous feature of these guns. Dropping one or even banging the hammer of a holstered revolver on the back of a chair may result in an unintended discharge and potentially lethal consequences. The half-cock position that allows the cylinder to be freely rotated for capping isn't a safety mechanism. A sufficiently hard blow will cause the sear to slip out of the half-cock notch and the gun will go off.

Nowadays shooters are advised that the only safe way to carry an old-fashioned sixgun is to load it with five rounds and lower the hammer on an empty chamber. This is certainly the best way, but I doubt if people did it that way in the Wild West. They carried the gun fully loaded and lowered the hammer onto the cylinder between nipples. The manufacturers recognized this as the normal practice and made provision for it.

Colt installed small, fragile pins into the rear cylinder face, and cut a slot in the hammer that fit over these pins. Remington cut slots in the rear of the cylinder, into which the flat hammer face fit snugly. The pins or slots would prevent the cylinder from rotating partially and bringing a cap under the hammer.

The Colt pins are quite fragile and easily deformed. A couple of hits on them from the hammer if the gun is out of time will flatten them into uselessness. Even ordinary wear will reduce their size and make them "slick" so that slight rotational force on the cylinder causes them to disengage. The Remington notches are a much better and more robust system, and will lock up the cylinder firmly. Neither is anywhere near as safe as the mechanisms in use on modern production revolvers.

CLEANING

I have spent a fair amount of time bent over a sink cleaning black powder revolvers, and on that basis I declare absolutely that the Colt design wins hands down over the Remington in this respect. The fact that you can detach the barrel and rammer assembly means that you can clean things thoroughly, from the breech end, holding it under a stream of running water to flush out the goo. The same is true of the cylinder. The frame and internal mechanism doesn’t get very dirty, and usually can be wiped clean with a damp cloth, then oiled.

The Remington, with its fixed barrel, requires cleaning from the muzzle; moreover, the grips have to be removed because you will get them wet in the process of cleaning. Fortunately, removing the grips from a Remington is a straightforward process, which it most certainly isn’t in a Colt. The Colt grips are one piece, and the backstrap has to be taken off to remove them.

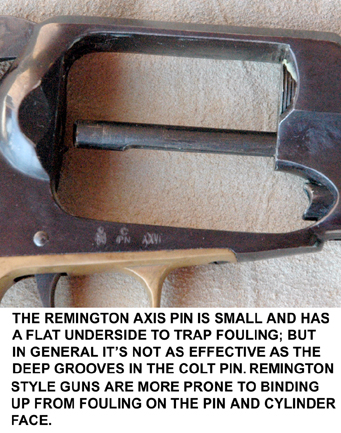

Another advantage in terms of cleaning and in function the Colt has is the design of the axis pin. It’s large and has deep grooves that allow fouling a place to go. Colt revolvers are much slower to bind up from fouling than are Remingtons. The wedge can also be tapped ever so gently either way to adjust the cylinder/barrel gap, another place where fouling tends to accumulate and bind the cylinder. The skinny axis pin and the solid frame of the Remington don’t allow for any of this, and every

Another advantage in terms of cleaning and in function the Colt has is the design of the axis pin. It’s large and has deep grooves that allow fouling a place to go. Colt revolvers are much slower to bind up from fouling than are Remingtons. The wedge can also be tapped ever so gently either way to adjust the cylinder/barrel gap, another place where fouling tends to accumulate and bind the cylinder. The skinny axis pin and the solid frame of the Remington don’t allow for any of this, and every  Remington style gun I have ever owned would bind up from fouling within a dozen shots. Sometimes, if the gun is new and tight it will bind up in fewer than six shots as black powder residue accumulates on the axis pin and on the face of the barrel’s forcing cone. I’ve never seen a Colt develop this problem.

Remington style gun I have ever owned would bind up from fouling within a dozen shots. Sometimes, if the gun is new and tight it will bind up in fewer than six shots as black powder residue accumulates on the axis pin and on the face of the barrel’s forcing cone. I’ve never seen a Colt develop this problem.

CAP FRAGMENTS

One of the things that drives shooters used to modern firearms nuts when they try percussion guns is the tendency of the caps to fall off when the muzzle is elevated; even worse, the tendency for fired caps to be blown off and get lodged in the action. Even normal breech pressure will usually cause a cap to be popped off the nipple, and that cap has to go somewhere. All too often, it goes into the space between the hammer pivot and the frame, interfering with normal operation and causing a jam until it’s removed.

One of the things that drives shooters used to modern firearms nuts when they try percussion guns is the tendency of the caps to fall off when the muzzle is elevated; even worse, the tendency for fired caps to be blown off and get lodged in the action. Even normal breech pressure will usually cause a cap to be popped off the nipple, and that cap has to go somewhere. All too often, it goes into the space between the hammer pivot and the frame, interfering with normal operation and causing a jam until it’s removed.

In my experience this is much more of an issue with Colts than Remingtons, but I don’t have a clear idea why that should be. Perhaps the greater clearance between the hammer face and the breech (the Colt hammer has to far enough back to serve as the rear sight) is the cause. Usually (not always) a cap can be removed by turning the gun upside down as the hammer is cocked, so that

In my experience this is much more of an issue with Colts than Remingtons, but I don’t have a clear idea why that should be. Perhaps the greater clearance between the hammer face and the breech (the Colt hammer has to far enough back to serve as the rear sight) is the cause. Usually (not always) a cap can be removed by turning the gun upside down as the hammer is cocked, so that  it falls out of the generous frame opening through which it entered. If it happens in a Remington, clearing the jam may require dismounting the (still loaded) cylinder and fishing the cap out from the crevices of the mechanism with a hook. Neither has an edge here, and the best solution is to avoid it by using properly fitting caps2, nipples in good condition (you should always have a complete spare set of new ones) and perhaps employing “cap guards,” short pieces of tubing that snug down over the sides of the cap and hold it in place, as well as seal it against moisture.

it falls out of the generous frame opening through which it entered. If it happens in a Remington, clearing the jam may require dismounting the (still loaded) cylinder and fishing the cap out from the crevices of the mechanism with a hook. Neither has an edge here, and the best solution is to avoid it by using properly fitting caps2, nipples in good condition (you should always have a complete spare set of new ones) and perhaps employing “cap guards,” short pieces of tubing that snug down over the sides of the cap and hold it in place, as well as seal it against moisture.

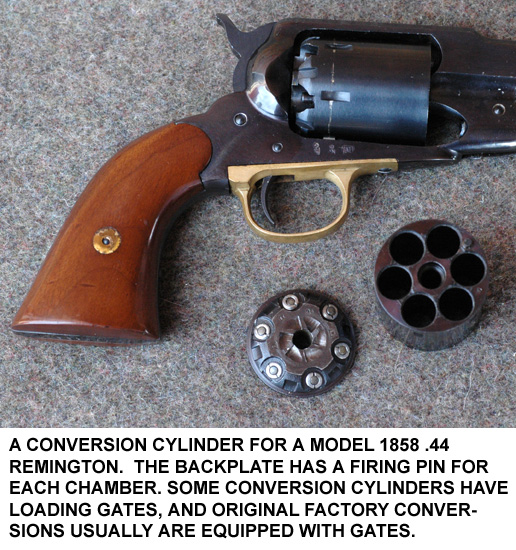

CONVERSIONS

The era in which percussion revolvers dominated the handgun scene was relatively brief. Development of practical fixed ammunition in the late 1850’s and the 1872 expiration of Smith & Wesson’s monopoly on cylinders bored through from the rear made percussion six-guns obsolete almost overnight. But because a good revolver represented a sizeable investment to its owner, ingenious methods for converting percussion guns to use fixed ammunition were put on the market rapidly. (Conversion cylinders are also available for modern replicas.)

The era in which percussion revolvers dominated the handgun scene was relatively brief. Development of practical fixed ammunition in the late 1850’s and the 1872 expiration of Smith & Wesson’s monopoly on cylinders bored through from the rear made percussion six-guns obsolete almost overnight. But because a good revolver represented a sizeable investment to its owner, ingenious methods for converting percussion guns to use fixed ammunition were put on the market rapidly. (Conversion cylinders are also available for modern replicas.)

The very first Colt revolver that used fixed ammunition was the Model 1872 “Open Top,” essentially a factory  conversion of the Model 1860 Army. Colt made it for a year as a way to use up spare M1860 parts and to enter the market for fixed-ammunition guns. Most conversions—of either type gun—were equipped with loading gates and ejector rods grafted onto the barrel. In 1873 the “Open Top” was retired from production and the solid frame Model 1873 “Peacemaker” was introduced. Remington introduced their version of a gun designed for fixed ammunition—a suitably modified Model 1858—in 1875.

conversion of the Model 1860 Army. Colt made it for a year as a way to use up spare M1860 parts and to enter the market for fixed-ammunition guns. Most conversions—of either type gun—were equipped with loading gates and ejector rods grafted onto the barrel. In 1873 the “Open Top” was retired from production and the solid frame Model 1873 “Peacemaker” was introduced. Remington introduced their version of a gun designed for fixed ammunition—a suitably modified Model 1858—in 1875.

Converted original guns are fairly common in collectors’ markets, and most of them seem to be Colts. This probably reflects the fact that more Colts were sold than were other brands, not any advantage to the Colt design. Loading and shooting either type of conversion would have been about the same, but the ease of breaking down a Colt for cleaning might well have been a deciding factor in whether or not to have the expensive conversion done.

WHICH IS BETTER?

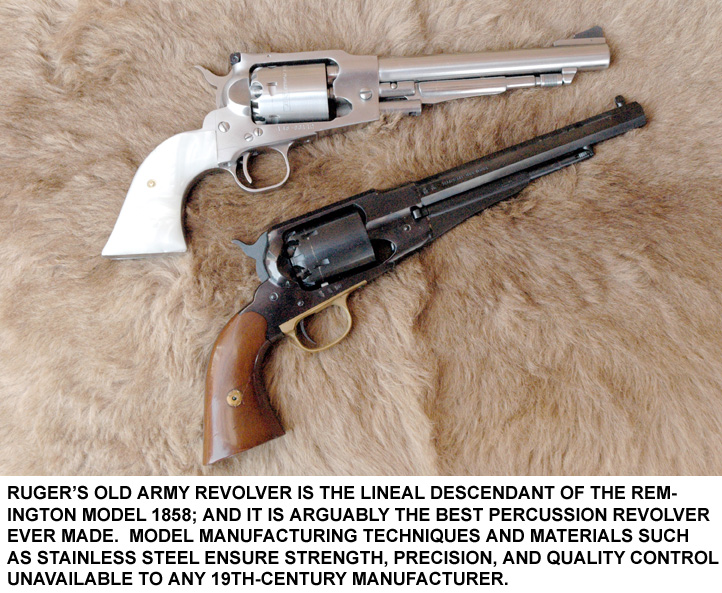

Balancing all these factors (and despite a personal preference for the Colt) I’ve to come to the conclusion that though Colts were more popular and more widely used, the Remington is probably the better design, on an objective basis.

History and the forces of the marketplace have a way of sorting out the wheat from the chaff. This is true in percussion revolvers as much as any other technological advance. It’s my belief that if somehow fixed ammunition had never been invented, the absolute zenith of handgun technology would be the Ruger Old Army .45 in stainless steel. The Old Army is essentially a vastly improved and greatly strengthened Model 1858 Remington. This gun is justifiably immensely popular among black powder handgunners, especially those who shoot in target competition.

The Old Army’s lineage can be easily seen in its design features. Though they differ in detail from the Model 1858, the Old Army takes advantage of Remington’s virtues to produce what is arguably the finest percussion revolver ever made. The strength and rigidity of the solid frame principle, the ability to install adjustable sights, and the rapid and simple takedown, coupled with Ruger’s modern materials and manufacturing methods make the Old Army—which isn’t old and was never used by any army, but let that pass—better than anything the 19th Century could have conceived, let alone built. Alas, this outstanding firearm has been dropped from Ruger’s product line.