JUST A CLOSER WALK WITH THEE

Everything that deceives may be said to enchant.

Plato: The Republic, III: 413

Surely the earliest weapon used by Man must have been a club? Even today a club can be very formidable in the hands of someone who knows how to use one: striking weapons such as the police officer’s baton, the knobkerrie, and the kubotan are common and useful. The high-ranking Army officer’s swagger stick is symbolic acknowledgement of the club’s role as an emblem of power and authority, as are the Queen’s Royal Sceptre...and the ceremonial mace carried by faculty marshals in academic processions!

The gentleman’s walking stick, that de rigueur fashion accessory for any well-dressed Victorian man-about-town, originated as a protection against assault. An elegantly dressed person was a lucrative target for a desperado, and a sturdy ebony cane with a sharp tip and heavy bronze head was not only chic but potentially lifesaving. Human ingenuity being what it is, someone inevitably gave thought to combining the common walking stick with something more assuredly effective. The best known such hybrid weapon is the sword cane, still made and used for personal defense. But both clubs and swords have significant drawbacks: you have to be in very close proximity to an assailant to use them effectively, and a sword also requires a fair amount of skill.

The gentleman’s walking stick, that de rigueur fashion accessory for any well-dressed Victorian man-about-town, originated as a protection against assault. An elegantly dressed person was a lucrative target for a desperado, and a sturdy ebony cane with a sharp tip and heavy bronze head was not only chic but potentially lifesaving. Human ingenuity being what it is, someone inevitably gave thought to combining the common walking stick with something more assuredly effective. The best known such hybrid weapon is the sword cane, still made and used for personal defense. But both clubs and swords have significant drawbacks: you have to be in very close proximity to an assailant to use them effectively, and a sword also requires a fair amount of skill.

I’m certain that not long after firearms were invented, it occurred to someone that joining a gun with a walking stick would produce a weapon of gratifyingly immediate lethality. While most readers will probably have at least a nodding acquaintance with a sword cane, it’s a safe bet that few will ever have encountered a functional example of the “rifle cane,” or “cane gun.”

Rifle canes were impractical in the days of matchlock ignition, but with the invention of mechanical locks, it was possible to design one that worked. There surely are a few wheel-lock examples in museums, and rifle canes were made on a custom basis in the flintlock era. The invention of the percussion cap and a more easily concealed firing mechanism made rifle canes really practical weapons. One Mr. John Day of Barnstaple, Devonshire, was granted British Patent #4861 for a rifle cane in 1823, using the then-new ignition system. Day’s rifle canes were made for may years: one example bearing Birmingham proof marks, and inscribed with the words “Day’s Patent” is known to have been made in 1859.

Rifle canes suited the needs of people who felt it wise to be armed but at the same time wanted to be reasonably discreet: gentleman farmers, country doctors, naturalists, clergymen, and ordinary citizens whose activities in society might have exposed them to danger but whose social environment precluded going about too obviously armed. In England a gentleman needing a rifle cane could have it custom made by his gunsmith, but in America the mass production methods of the Industrial Revolution were directed to satisfying this niche market. In the long-settled regions of the American East where openly carrying firearms wasn’t the norm as it was in the West, people bought rifle canes in moderate numbers. They enjoyed a brief popularity during a time when society acknowledged the need for personal protection, and when there were few or no laws restricting possession or use of concealed weapons.

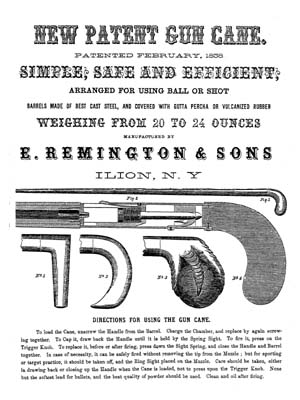

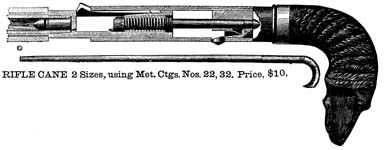

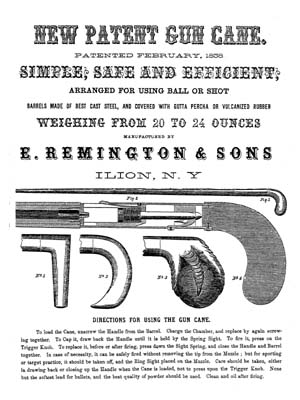

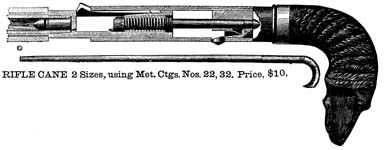

Of the commercial models the best known is the rifle cane made by Remington from the mid 1860’s to the late 1880’s. These were openly advertised as protection against stray dogs and “footpads.” The early versions were percussion-fired, and came in .31 and .44 caliber, but after about 1866 they were made as .22 or .32 caliber rimfire breechloaders. Remington rifle canes aren’t common, as fewer than 2000 were made in all. These were originally classified by the BATF in the "Any Other Weapon" category of the National Firearms Act of 1934, putting them in the same general category as pen pistols, sawed off shotguns, and so forth. At some point during the 1980's someone in BATF came to their senses and the rare Remington Rifle cane is today permissible for ordinary citizens to own. Of course, they're far too expensive to shoot even if ammunition were available, which it isn't. In good condition an original Remington commands a price of $2000 to $5000 today.

Of the commercial models the best known is the rifle cane made by Remington from the mid 1860’s to the late 1880’s. These were openly advertised as protection against stray dogs and “footpads.” The early versions were percussion-fired, and came in .31 and .44 caliber, but after about 1866 they were made as .22 or .32 caliber rimfire breechloaders. Remington rifle canes aren’t common, as fewer than 2000 were made in all. These were originally classified by the BATF in the "Any Other Weapon" category of the National Firearms Act of 1934, putting them in the same general category as pen pistols, sawed off shotguns, and so forth. At some point during the 1980's someone in BATF came to their senses and the rare Remington Rifle cane is today permissible for ordinary citizens to own. Of course, they're far too expensive to shoot even if ammunition were available, which it isn't. In good condition an original Remington commands a price of $2000 to $5000 today.

The rifle cane may be technically obsolete, and modern industrial nations less tolerant of people going about discreetly armed than might have been the case in, say, New York City in the 1880’s. But the basic concept is as valid as it was then, and occasionally one runs across a “modern” rifle cane like the specimen shown here at right. This one, though of modern make, is not covered by the National Firearms Act, because it uses loose pwder and ball: it is therefore an unregulated "antique" exempt from all Federal laws.

The rifle cane may be technically obsolete, and modern industrial nations less tolerant of people going about discreetly armed than might have been the case in, say, New York City in the 1880’s. But the basic concept is as valid as it was then, and occasionally one runs across a “modern” rifle cane like the specimen shown here at right. This one, though of modern make, is not covered by the National Firearms Act, because it uses loose pwder and ball: it is therefore an unregulated "antique" exempt from all Federal laws.

I acquired this gun brand new more than 20 years ago from Walter Craig, Inc. in Selma, Alabama. I have no idea where it was made, or who the maker was. It is completely unmarked, and it’s such a simple device it could easily have been made on a lathe in someone’s basement workshop. The “action” is little more than a heavy-walled piece of steel tubing with appropriate cuts for the striker mechanism and threading at each end to match the barrel and handle. The original barrel was a 15-cm .36 caliber smoothbore tube press-fitted into a hollow sleeve that served as the main shaft of the cane. A low price was enough to make it an attractive “impulse” purchase, but unfortunately I soon found that I couldn’t hit anything with it unless I was practically touching my target with the tip. A man-sized target at 5 metres was an iffy proposition at best, and the wimpy .36 caliber round ball it used was ballistically ineffective. I decided it was an interesting curiosity and a nice noise-maker, but that was about all; I tossed it into a closet and forgot about it.

Nevertheless, it nagged at me. It reproached me every time I spotted it in the corner of my closet. My sensibilities were outraged at the thought of what was at least theoretically a weapon, doing nothing but gathering dust! So, when some years later, I was given a non-functional single-barrel .45 caliber percussion rifle, an inspiration struck. The barrel of that gun was in good condition, and just about the same length as the useless one on the rifle cane. Forthwith I had a local gunsmith turn the barrel to the same external diameter as the original; and breech it to fit the firing mechanism of the cane. Presto, my closet-dwelling curio was transformed into a useful self-defense article!

Nevertheless, it nagged at me. It reproached me every time I spotted it in the corner of my closet. My sensibilities were outraged at the thought of what was at least theoretically a weapon, doing nothing but gathering dust! So, when some years later, I was given a non-functional single-barrel .45 caliber percussion rifle, an inspiration struck. The barrel of that gun was in good condition, and just about the same length as the useless one on the rifle cane. Forthwith I had a local gunsmith turn the barrel to the same external diameter as the original; and breech it to fit the firing mechanism of the cane. Presto, my closet-dwelling curio was transformed into a useful self-defense article!

It’s a breechloader using the screw-barrel principle: the barrel is unscrewed from the “action” and a ball (with a lubricated felt wad behind it) thumb-pressed into the breech end. The powder recess in the “action” is filled with about 15 grains of FFFg black powder and the barrel is screwed back into place, starting the bullet into the rifling and sealing the breech. After a percussion cap is seated on the nipple it’s ready to fire. The firing mechanism is simplicity itself: a strong spring-loaded striker that can be slid back into a “safety” notch and pushed off with the thumb to fire the cap and ignite the main charge.

It’s a breechloader using the screw-barrel principle: the barrel is unscrewed from the “action” and a ball (with a lubricated felt wad behind it) thumb-pressed into the breech end. The powder recess in the “action” is filled with about 15 grains of FFFg black powder and the barrel is screwed back into place, starting the bullet into the rifling and sealing the breech. After a percussion cap is seated on the nipple it’s ready to fire. The firing mechanism is simplicity itself: a strong spring-loaded striker that can be slid back into a “safety” notch and pushed off with the thumb to fire the cap and ignite the main charge.

With the rifled barrel it’s surprisingly accurate, considering the crude slam-fire mechanism and the total lack of sights. After a few rounds to get the feel of how it shot, I found it was no trick to put 5 bullets into a 10-cm circle at 6 metres. It has a tendency to shoot higher than where I think it will, but a couple of practice sessions have made me able to place a bullet right in the center of a target the size of a man’s chest any time I like.

Since long range shots aren’t a concern, any kind of bullet that fits the bore works quite well. Groove diameter is 0.450” which is standard for muzzle-loader barrels. I’ve been using lead balls of 0.451” diameter for convenience, but get equally satisfactory results with a 230-grain lead round-nosed bullet designed for the .45 ACP cartridge, sized to 0.452”. The LRN bullet doesn’t require a lubricated felt wad, as it has its own lubricant groove. I can even fire saboted projectiles, using bullets for a 9mm pistol or .38 revolver, though that is more trouble than it’s worth, since there is no real gain in performance. Besides being able to shoot a big bullet, it’s heavy enough to make an effective club!

Since long range shots aren’t a concern, any kind of bullet that fits the bore works quite well. Groove diameter is 0.450” which is standard for muzzle-loader barrels. I’ve been using lead balls of 0.451” diameter for convenience, but get equally satisfactory results with a 230-grain lead round-nosed bullet designed for the .45 ACP cartridge, sized to 0.452”. The LRN bullet doesn’t require a lubricated felt wad, as it has its own lubricant groove. I can even fire saboted projectiles, using bullets for a 9mm pistol or .38 revolver, though that is more trouble than it’s worth, since there is no real gain in performance. Besides being able to shoot a big bullet, it’s heavy enough to make an effective club!

A single-shot weapon is obviously not a prime defensive tool. No one who didn’t have to would carry a rifle cane in preference to a conventional handgun. But I can conceive of circumstances in which it might be a viable choice, whose real value would undoubtedly be the element of surprise. Imagine the look on a mugger’s face if some old lady he’d accosted pointed her cane at him; and the even greater surprise he’d get if she shot him with it!

The gentleman’s walking stick, that de rigueur fashion accessory for any well-dressed Victorian man-about-town, originated as a protection against assault. An elegantly dressed person was a lucrative target for a desperado, and a sturdy ebony cane with a sharp tip and heavy bronze head was not only chic but potentially lifesaving. Human ingenuity being what it is, someone inevitably gave thought to combining the common walking stick with something more assuredly effective. The best known such hybrid weapon is the sword cane, still made and used for personal defense. But both clubs and swords have significant drawbacks: you have to be in very close proximity to an assailant to use them effectively, and a sword also requires a fair amount of skill.

The gentleman’s walking stick, that de rigueur fashion accessory for any well-dressed Victorian man-about-town, originated as a protection against assault. An elegantly dressed person was a lucrative target for a desperado, and a sturdy ebony cane with a sharp tip and heavy bronze head was not only chic but potentially lifesaving. Human ingenuity being what it is, someone inevitably gave thought to combining the common walking stick with something more assuredly effective. The best known such hybrid weapon is the sword cane, still made and used for personal defense. But both clubs and swords have significant drawbacks: you have to be in very close proximity to an assailant to use them effectively, and a sword also requires a fair amount of skill.  Of the commercial models the best known is the rifle cane made by Remington from the mid 1860’s to the late 1880’s. These were openly advertised as protection against stray dogs and “footpads.” The early versions were percussion-fired, and came in .31 and .44 caliber, but after about 1866 they were made as .22 or .32 caliber rimfire breechloaders. Remington rifle canes aren’t common, as fewer than 2000 were made in all. These were originally classified by the BATF in the "Any Other Weapon" category of the National Firearms Act of 1934, putting them in the same general category as pen pistols, sawed off shotguns, and so forth. At some point during the 1980's someone in BATF came to their senses and the rare Remington Rifle cane is today permissible for ordinary citizens to own. Of course, they're far too expensive to shoot even if ammunition were available, which it isn't. In good condition an original Remington commands a price of $2000 to $5000 today.

Of the commercial models the best known is the rifle cane made by Remington from the mid 1860’s to the late 1880’s. These were openly advertised as protection against stray dogs and “footpads.” The early versions were percussion-fired, and came in .31 and .44 caliber, but after about 1866 they were made as .22 or .32 caliber rimfire breechloaders. Remington rifle canes aren’t common, as fewer than 2000 were made in all. These were originally classified by the BATF in the "Any Other Weapon" category of the National Firearms Act of 1934, putting them in the same general category as pen pistols, sawed off shotguns, and so forth. At some point during the 1980's someone in BATF came to their senses and the rare Remington Rifle cane is today permissible for ordinary citizens to own. Of course, they're far too expensive to shoot even if ammunition were available, which it isn't. In good condition an original Remington commands a price of $2000 to $5000 today.  The rifle cane may be technically obsolete, and modern industrial nations less tolerant of people going about discreetly armed than might have been the case in, say, New York City in the 1880’s. But the basic concept is as valid as it was then, and occasionally one runs across a “modern” rifle cane like the specimen shown here at right. This one, though of modern make, is not covered by the National Firearms Act, because it uses loose pwder and ball: it is therefore an unregulated "antique" exempt from all Federal laws.

The rifle cane may be technically obsolete, and modern industrial nations less tolerant of people going about discreetly armed than might have been the case in, say, New York City in the 1880’s. But the basic concept is as valid as it was then, and occasionally one runs across a “modern” rifle cane like the specimen shown here at right. This one, though of modern make, is not covered by the National Firearms Act, because it uses loose pwder and ball: it is therefore an unregulated "antique" exempt from all Federal laws.  Nevertheless, it nagged at me. It reproached me every time I spotted it in the corner of my closet. My sensibilities were outraged at the thought of what was at least theoretically a weapon, doing nothing but gathering dust! So, when some years later, I was given a non-functional single-barrel .45 caliber percussion rifle, an inspiration struck. The barrel of that gun was in good condition, and just about the same length as the useless one on the rifle cane. Forthwith I had a local gunsmith turn the barrel to the same external diameter as the original; and breech it to fit the firing mechanism of the cane. Presto, my closet-dwelling curio was transformed into a useful self-defense article!

Nevertheless, it nagged at me. It reproached me every time I spotted it in the corner of my closet. My sensibilities were outraged at the thought of what was at least theoretically a weapon, doing nothing but gathering dust! So, when some years later, I was given a non-functional single-barrel .45 caliber percussion rifle, an inspiration struck. The barrel of that gun was in good condition, and just about the same length as the useless one on the rifle cane. Forthwith I had a local gunsmith turn the barrel to the same external diameter as the original; and breech it to fit the firing mechanism of the cane. Presto, my closet-dwelling curio was transformed into a useful self-defense article! It’s a breechloader using the screw-barrel principle: the barrel is unscrewed from the “action” and a ball (with a lubricated felt wad behind it) thumb-pressed into the breech end. The powder recess in the “action” is filled with about 15 grains of FFFg black powder and the barrel is screwed back into place, starting the bullet into the rifling and sealing the breech. After a percussion cap is seated on the nipple it’s ready to fire. The firing mechanism is simplicity itself: a strong spring-loaded striker that can be slid back into a “safety” notch and pushed off with the thumb to fire the cap and ignite the main charge.

It’s a breechloader using the screw-barrel principle: the barrel is unscrewed from the “action” and a ball (with a lubricated felt wad behind it) thumb-pressed into the breech end. The powder recess in the “action” is filled with about 15 grains of FFFg black powder and the barrel is screwed back into place, starting the bullet into the rifling and sealing the breech. After a percussion cap is seated on the nipple it’s ready to fire. The firing mechanism is simplicity itself: a strong spring-loaded striker that can be slid back into a “safety” notch and pushed off with the thumb to fire the cap and ignite the main charge.  Since long range shots aren’t a concern, any kind of bullet that fits the bore works quite well. Groove diameter is 0.450” which is standard for muzzle-loader barrels. I’ve been using lead balls of 0.451” diameter for convenience, but get equally satisfactory results with a 230-grain lead round-nosed bullet designed for the .45 ACP cartridge, sized to 0.452”. The LRN bullet doesn’t require a lubricated felt wad, as it has its own lubricant groove. I can even fire saboted projectiles, using bullets for a 9mm pistol or .38 revolver, though that is more trouble than it’s worth, since there is no real gain in performance. Besides being able to shoot a big bullet, it’s heavy enough to make an effective club!

Since long range shots aren’t a concern, any kind of bullet that fits the bore works quite well. Groove diameter is 0.450” which is standard for muzzle-loader barrels. I’ve been using lead balls of 0.451” diameter for convenience, but get equally satisfactory results with a 230-grain lead round-nosed bullet designed for the .45 ACP cartridge, sized to 0.452”. The LRN bullet doesn’t require a lubricated felt wad, as it has its own lubricant groove. I can even fire saboted projectiles, using bullets for a 9mm pistol or .38 revolver, though that is more trouble than it’s worth, since there is no real gain in performance. Besides being able to shoot a big bullet, it’s heavy enough to make an effective club!