A CABIN IN THE WOODS

There are milestones in everyone's life: one of the most important is the purchase of one's first house. I passed that milestone 40 years ago this November.

We were apartment dwellers: I had done my doctorate in Georgetown University's Biology Department and in June of 1980 took a position as a postdoctoral research fellow at George Washington University's School of Medicine. We got married in 1975 had been living in an apartment in the District of Columbia for several years. As comfortable and as pleasant  as our apartment was, it was...well, it was an apartment. We wanted some space and some privacy beyond what we had. I wanted a place where I could go hunting. We both had jobs, so we decided to buy a place in the country, with some land.

as our apartment was, it was...well, it was an apartment. We wanted some space and some privacy beyond what we had. I wanted a place where I could go hunting. We both had jobs, so we decided to buy a place in the country, with some land.

We found a cabin for sale in a place called Burr Hill, Virginia. Burr Hill isn't a town, it isn't even a village, at least it wasn't in 1980. It was more or less a few properties along stretch of State Route 611 between Locust Grove and Raccoon Ford (I swear I'm not making up these names). A mile or two down the road was a small general store-gas station-Post Office of the sort you see in movies, run by a genial lady named Glenda.

I used "General Delivery, Burr Hill," as my address because our place didn't have an actual street address then (it does now). Every week I'd stop in, chat with Glenda, and pick up my mail, most of which consisted of an electricity and/or a telephone bill. That store is closed now, Glenda is gone, and more and more houses are being built; the completely rural nature of Burr Hill is being rapidly eroded.

We bought the place on a "balloon note," one of those "creative mortgages" that suckers like first-time buyers fall for all too often. The seller/owner agreed to hold the mortgage for 5 years, with monthly payments calculated on a 20-year schedule. At the end of 5 years we had to pay off the note. Getting into such an arrangement was an extraordinarily stupid thing to do, but we knew no better at the time. Furthermore he offered it to us at an interest rate of only 9%. Today that rate sounds extortionate, something the Mafia would charge. But during Jimmy Carter's "stagflation" era, typical mortgage rates at banks were running much higher: 15-17% was considered reasonable. The owners were going through a bitter divorce (at the closing they never spoke one word to each other!) and needed to get shed of the place, split the money, and be done with it.

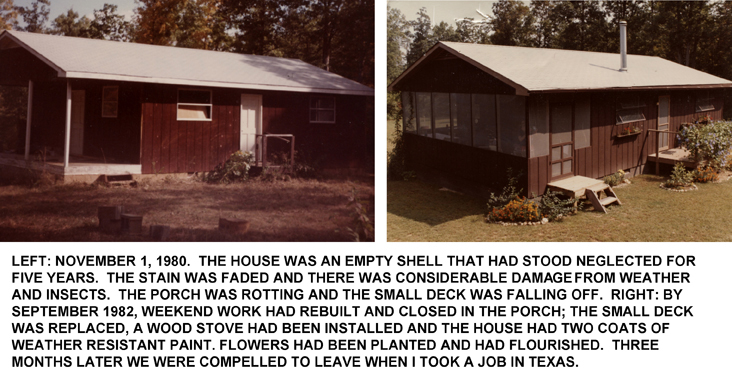

What we bought was an unfinished shell cabin on 28 acres, mostly wooded. It wasn't much of a house but we were young enough to do the fixing-up ourselves (I wasn't quite 33 at the time). The price was within our budget, and we had every expectation of being around to use it for a long time.

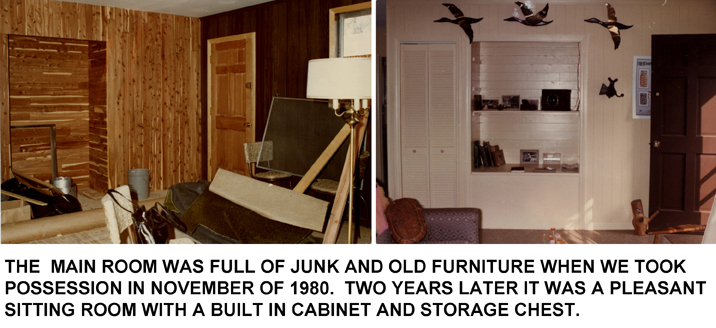

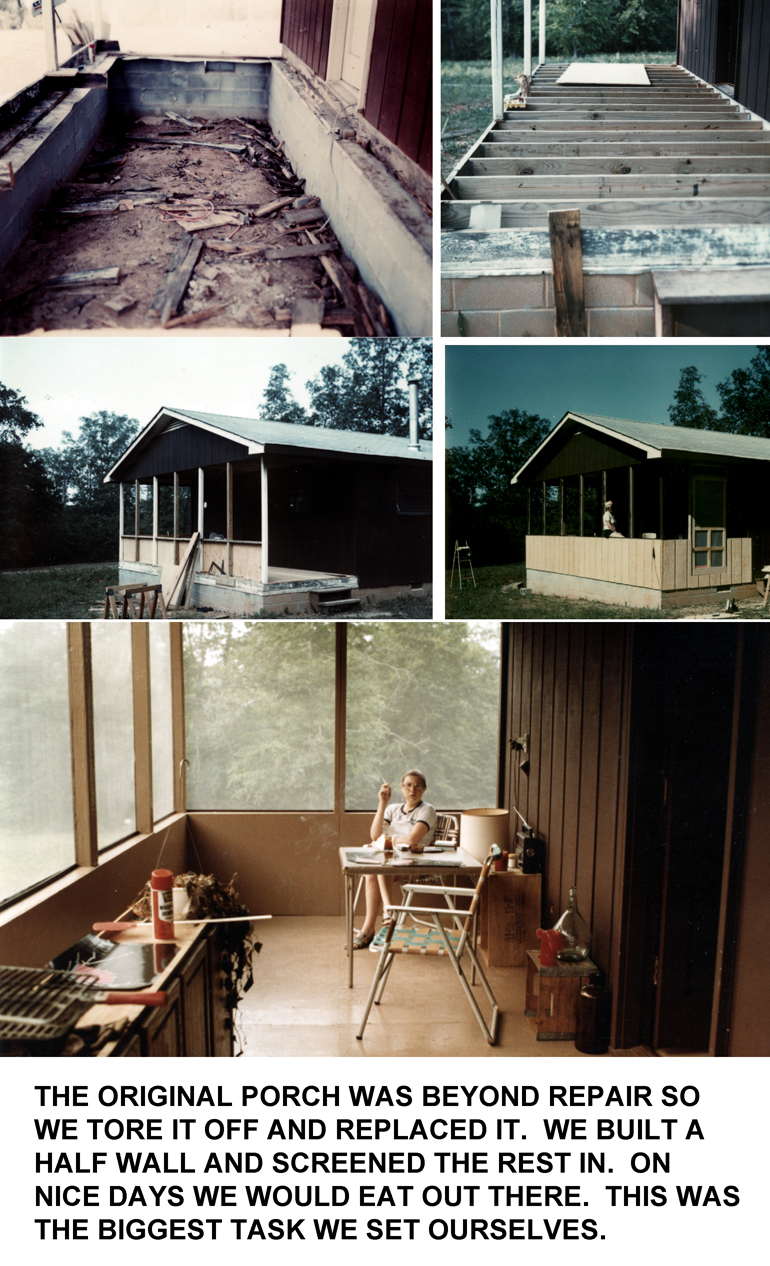

We went to closing on November 11th, 1980. The cabin proper was what real estate people laughingly refer to as a "fixer-upper," and boy, did it need fixing up. It was originally constructed in 1974; it had stood unattended and un-maintained for six years but it was still sound enough to keep the rain out. Interior walls were in place for two bedrooms and a single bathroom. The floor was raw plywood of the cheapest grade: some basic (very basic) kitchen appliances were in place and some old furniture—stuff any respectable thrift shop would have rejected—had been left behind. Since there was no heat, during a previous winter the water heater and the toilet had frozen solid and been destroyed. We had our work cut out for us.

Our first step was to clean out the junk: the leftover construction material and debris and the old furniture that had been left inside. We bought a tin shed from Montgomery Ward, tossed a lot of stuff out and stored the rest in that, clearing enough room for repairs and fixing up to be done. That took up most of the winter of 1980, during

Our first step was to clean out the junk: the leftover construction material and debris and the old furniture that had been left inside. We bought a tin shed from Montgomery Ward, tossed a lot of stuff out and stored the rest in that, clearing enough room for repairs and fixing up to be done. That took up most of the winter of 1980, during  which time we had no toilet facilities beyond a shovel, a roll of TP, and 28 acres of land, a situation for which my wife has never forgiven me. Later, when the warm weather came we were in better shape because I could install a new water heater and toilet!

which time we had no toilet facilities beyond a shovel, a roll of TP, and 28 acres of land, a situation for which my wife has never forgiven me. Later, when the warm weather came we were in better shape because I could install a new water heater and toilet!

We slaved over that place ever weekend for two and a half years. We laid subflooring, we tiled the floors in all the rooms, painted inside and out, and did major repairs on the fabric of the building where weather and rot and insects had made inroads. Burr Hill became the focus of our lives. Every Friday my wife would pick me up at GWU and we'd be off down Interstate 95 to work on the house, hauling stuff in and on top of her  greatly overloaded Chevrolet Vega hatchback, including once a huge load of 4'x8' plywood sheets on a roof rack. I won't go into detail

greatly overloaded Chevrolet Vega hatchback, including once a huge load of 4'x8' plywood sheets on a roof rack. I won't go into detail on all the work we did: much of it (by no means all) is summarized in the images here. I steadfastly refused to countenance the presence of a TV set, but as a concession to necessity I agreed to have a telephone line installed.

on all the work we did: much of it (by no means all) is summarized in the images here. I steadfastly refused to countenance the presence of a TV set, but as a concession to necessity I agreed to have a telephone line installed.

In time our efforts paid off by creating a cozy retreat, a place to escape the miscellaneous stresses of city life such as traffic and profoundly annoying neighbors in our apartment building. I was even able to do a little hunting. For me Burr Hill became not just "a cabin in the woods," it became my refuge, my haven. I came to love that place so much that could I have managed it financially, I'd have quit my job and moved there permanently. But weekends were all I got. We'd arrive on a Friday evening, stay that night and the following Saturday night, then return to DC on Sunday afternoon. I always pleaded to stay over until Monday but only once did I convince my wife to do so. I used to joke that if we looked towards the north and there was a bright flash on the horizon we'd know the Russians had hit DC and we could just stay where we were.

Eventually there came the hardest blow of all, one from which I've never really recovered, even after all this time. In mid-1982 my post-doc ended and I had to find a job. I did find one, but it wasn't in the DC area: it was in Texas. We had to move. Our "balloon" note was due to be paid off in November of 1985, with about $33,000 still owing. We left for Texas in December of 1982. We rented the house out for a couple of years and listed it with two real estate agents, one of whom eventually found a buyer. We lost money on the sale: we sold for less than we'd paid, but in addition we lost the thousands of dollars we'd spent on materials and repairs. But I lost more than that: that cabin wasn't just plywood, paint, and plumbing. I'd put my  heart's blood into it along with not a little sweat and

heart's blood into it along with not a little sweat and  some tears. It was a place where I was home in a very real sense, far more so than my apartment in DC. With the move it was all gone; not just the money, but the love and happiness I felt when I was there. I have resented having been forced to give up my sanctuary for the past four decades. I will carry that sorrow to my grave.

some tears. It was a place where I was home in a very real sense, far more so than my apartment in DC. With the move it was all gone; not just the money, but the love and happiness I felt when I was there. I have resented having been forced to give up my sanctuary for the past four decades. I will carry that sorrow to my grave.

Financially we made an even more colossal blunder than that balloon note by not hanging on to the place. A few years after we left a commuter Light Rail line was built; what had been a wide spot in the road is now a bustling exurb for DC, and the 28 acres I once owned is only 18 miles from the railhead. The assessed valuation is well over half a million dollars, about 15 times what we paid for the place in 1980. Looking back I now know I could have financed the house with a VA note but I was too dumb and too naive to have done it when I could have. In the end the cabin did sort of "give back" and in some ways repaid my investment, though not in money. Fixing it up taught me a great deal about do-it-yourself work, something which has stood me in good stead over the years. I've undoubtedly saved a huge amount of money in my present home by doing things myself, using skills I developed in Burr Hill.

Another very real benefit we gained from it was that it saved us from buying a house in Texas. By the time we arrived there mortgage interest rates were 17-18% which is unbelievable today, but true. Since we were carrying that balloon note we were completely unable to buy a house in College Station. Had we not had the cabin we might foolishly have done so at a time just before the oil market collapsed. We'd never have been able to get out from under one of those 17% notes; that thought makes my skin crawl, so at least financially Burr Hill saved me from a worse fate.

Another very real benefit we gained from it was that it saved us from buying a house in Texas. By the time we arrived there mortgage interest rates were 17-18% which is unbelievable today, but true. Since we were carrying that balloon note we were completely unable to buy a house in College Station. Had we not had the cabin we might foolishly have done so at a time just before the oil market collapsed. We'd never have been able to get out from under one of those 17% notes; that thought makes my skin crawl, so at least financially Burr Hill saved me from a worse fate.

But forty years later what I miss most is what I had there: not just a cabin but serenity, peace, the feeling that however badly things were going elsewhere, there things were right and good. I have so many memories I could never put them all down here: of painting folding closet doors bright yellow while listening to the radio broadcast of the first Space Shuttle launch; of Saturday evening broadcasts of A Prairie Home Companion; of a deer bounding across the lawn one Spring morning; the call of whippoorwills at night, tiny birds that would wake us up with incredibly loud cries; the satisfying fatigue after a long day of manual labor; and of one hilarious day when a neighbor's cows wandered into the yard and wandered out again. All good memories, no bad ones. Looking back, I think I can say truthfully that mid-1982 was the last time I was truly, completely content. But it all went for naught and came crashing down when I was forced to sell my very own small piece of Paradise.

Addendum, November 3, 2020: What It Looks Like Now

I tracked the place down on the Orange County Property Records site. It's changed hands at least once more since I sold it; the current owners have made considerable changes. They've essentially built a new house onto the end of it. The roof has been replaced; the porch I so laboriously rebuilt has been ripped off; the windows are all new. It has electric heat and window air conditioners. But what frosts my cake is that the Orange County site refers to the original cabin (in the foreground in this picture) as an "addition"!

|SEASON LOGS |

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |