HOW—AND WHY—TO GET PAST AMMUNITION SHORTAGES

It's no secret that at times certain calibers of ammunition have been difficult, and at times impossible, to find. Two recent examples: a couple of years ago, it was nearly impossible to locate .380 ACP, and at times .22 Long Rifle ammunition has been as scarce as frog hair. There are various reasons for these two occurrences and not a few theories about conspiracies on the part of the government, industry, or both, bringing them about.

It's no secret that at times certain calibers of ammunition have been difficult, and at times impossible, to find. Two recent examples: a couple of years ago, it was nearly impossible to locate .380 ACP, and at times .22 Long Rifle ammunition has been as scarce as frog hair. There are various reasons for these two occurrences and not a few theories about conspiracies on the part of the government, industry, or both, bringing them about.

The origin of some shortages is simple: hoarding by panicked people. During the acute shortage of .22 rimfire the ammunition companies were running production lines full blast, three shifts, but they couldn't keep up with the demand. A very rational fear of what the government might do, and what its plans might be, led shooters to buy as much .22 ammunition as they could find, at any price.

Consider this: virtually every gun owner in the USA (all 100 million of them) has a .22-caliber gun of some kind and many have more than one. The total production capacity for .22 LR ammunition is a pretty heavily guarded industrial secret but it's certainly something on the order of 3 to 4 billion (with a "b") rounds per year. If those 100 million gun owners were to buy two bricks per month (1000 rounds) 1,000,000,000 cartridges would immediately be taken out of general circulation and in only four months an entire year's production would vanish into closets and safes. And that's exactly what happened in the last .22 shortage. It wasn't being shot up, it was being stashed away because no one was certain whether things would ease up and ammunition would again become available on demand. Some of it was purchased with a view to re-sale on the private market by speculators. But it wasn't a conspiracy, panic buying and greed drove that shortage.

The shortage of .380 ACP was attributable to the liberalization of concealed weapon laws in many places, and the surge in demand for small, easily concealed guns by newly-licensed individuals. Since the .380 is one of the best options for small guns, it promptly vanished from store shelves; once the market for that caliber was satisfied the continuing production caught up and it's now available again.

Another example is the "primer shortage" of perhaps 5 years back. For a while primers in rifle and pistol sizes were simply impossible to get. In this case the government may have had an unintentional role. The miscellaneous wars in the Middle East were burning up ammunition in staggering quantities, and perforce the factories had to give priority to loading ammunition for military contracts. When the Army buys cartridges by the billions, it's a cinch that ammunition makers will see to it they get what they want, and civilian reloaders take a back seat.

But to be honest, a fair bit of the problem with sporadic shortages can properly be laid at the feet of anti-gun politicians and in particular the (now thankfully ended) Obama administration, the most anti-gun in US history (so far). Obama's BATF restricted imports of many popular calibers on the grounds that they're used in "assault weapons" and stopped any importation of ammunition from Russia, excusing this blatantly anti-gun action as part of the "economic sanctions" imposed after the invasion of Ukraine. Nevertheless, if the government had somehow deliberately caused the shortages—and I'm sure the Obama Administration would have been happy to do so if they could have—the most affected calibers would be .223, .308, and 9mm Parabellum, not .22's.

But to be honest, a fair bit of the problem with sporadic shortages can properly be laid at the feet of anti-gun politicians and in particular the (now thankfully ended) Obama administration, the most anti-gun in US history (so far). Obama's BATF restricted imports of many popular calibers on the grounds that they're used in "assault weapons" and stopped any importation of ammunition from Russia, excusing this blatantly anti-gun action as part of the "economic sanctions" imposed after the invasion of Ukraine. Nevertheless, if the government had somehow deliberately caused the shortages—and I'm sure the Obama Administration would have been happy to do so if they could have—the most affected calibers would be .223, .308, and 9mm Parabellum, not .22's.

Executive Actions can have and have had a noticeable effect on supplies, but there was not—as has not yet been—any organized government-led plot to create the problem. That may not always be the case. While President Obama could legitimately be considered the "Salesman of the Century " by the gun and ammunition makers, now (thankfully) he's gone; provided we don't get someone even worse the situation should improve. But make no mistake: we could get someone even worse. Given the current situation in the US Congress and the outrageous proposals some candidates for the Democratic nomination have put forward, we could be in for a very hard time in years ahead.

Even now the price of ammunition continues to climb, partly because of pumped-up demands, but also because of the increasing cost of raw materials. A look at the prices for copper, brass, and lead over the past 5 years shows a steadily rising price for scrap on the various metals exchanges. What was selling for 30 cents per pound 10 years ago now fetches ten times as much or more. This is the result of rapid economic development in China and India, two countries with colossal populations (roughly three billion between them) and rising middle classes. A lot of metal goes into the average automobile: if 10% of the population of those two countries are now able to afford a car, 300 million more cars will be built, using scrap mostly from the USA. The junkyards of America are the source of supply for the rising lifestyle expectations of the Third World.

All these things are reflected in the price of other products that also depend on availability of lead and brass. So when a given shortage due to manufacturing shortfalls or other issues eases, prices for popular calibers will remain well above where they were when the shortage started just for that reason. Simple supply-and-demand economics dictates that this will happen when scrap dealers get more money by selling to the Chinese and Indians than to the cartridge makers.

We are never going to see $1-a-box .22 LR again : shooters must re-align their thinking. Cheap ammunition is not coming back, certainly not at the prices some of us can remember from easier times. Expending 500 rounds of .22 LR in a three hour session at the range every weekend is no longer a realistic expectation for most people.

Now, of course Obama's EPA didn't help. While not so publicized as their "War On Coal," they ramped up their less publicized all-out assault against lead, specifically by vastly increasing the cost of processing lead scrap. The last American smelter making lead from ore was closed down during Obama's term. The Hard Left Eco-Nazi movement, led by the "Center For Biological Diversity," continues the war on lead, not only at the Federal but at the state level. California, always a leader in bad ideas, has completely banned the use of lead ammunition, and other states may soon follow suit. (Another screwy idea: California also now requires a background check to buy ammunition, a tactic clearly intended to intimidate people into shooting less and eventually to stop shooting at all. This will certainly be repeated in places like New York and Illinois, among others. And in their world, what passes for logic dictates that if you aren't shooting...well, you have no need for a gun, now do you? Not incidentally, places like that always have mandatory firearms registration, whose only purpose is to facilitate taking away those guns you "...can't use anymore." These people never give up and they never go away.)

Someone gifted with foresight—or at least having less of the blinkered complacency that afflicts too many American shooters and hunters—could have spotted the handwriting on the wall during the Clinton Administration, if not before that. Anyone who did see what was coming stocked up when ammunition was far cheaper than it is now. Furthermore, no doubt some people took Janet Reno's proposals for "arsenal licenses" and ammunition taxes seriously in 1994, and tucked away a few thousand rounds of .22 LR; but most people didn't.

So the question is: how do we get around a situation in which ammunition supplies become restricted, either by economic or political pressure? How do we continue to shoot and hunt when—not if, when—times get tough? Obviously, at the very least we need to be more selective about what we shoot, why we shoot, and how we shoot. I'm not saying we shouldn't shoot, and I'm certainly not saying we shouldn't practice enough to keep our skills sharp; but for the average person (and especially the average hunter) that probably requires quite a lot less shooting for "fun" than has been the case in the past, and more shooting with a purpose. How to do this? How to have enough ammunition to practice properly, to hunt when you like, or to defend yourself and your family? I offer some suggestions below.

The first strategy is simple and obvious: reload your ammunition. Any centerfire caliber, no matter how obscure, can be reloaded. The equipment needed and supplies required aren't expensive, nor are they hard to get (yet). A complete, brand-new reloading kit from, say Lee Precision, is less than $200, and you can get kitted out for much less if you're willing to buy good-quality used equipment at gun shows and gun shops. There's quite a bit of it out there, most of it a bit dusty but still in excellent mechanical condition.

The first strategy is simple and obvious: reload your ammunition. Any centerfire caliber, no matter how obscure, can be reloaded. The equipment needed and supplies required aren't expensive, nor are they hard to get (yet). A complete, brand-new reloading kit from, say Lee Precision, is less than $200, and you can get kitted out for much less if you're willing to buy good-quality used equipment at gun shows and gun shops. There's quite a bit of it out there, most of it a bit dusty but still in excellent mechanical condition.

There will no doubt be restrictions proposed (and eventually imposed) on the purchase of primers and powder, and perhaps cartridge cases and bullets, sooner or later. Several countries already do this and at least one state has begun the process of restricting access to components. But right now that's not the case in the USA across the board. A few hundred dollars invested in a low-cost kit for reloading centerfire ammunition, a hundred or so empty cases (or better yet, factory loaded ammunition) primers and powder will be repaid in time.

Reloading is very economical. Charges for use in handgun calibers can be very small, and a pound goes a long, long way. One pound of Alliant Unique, doled out at a measly 5 grains per cartridge, gives you 1400 shots of 9mm. In a typical rifle caliber a pound of IMR 3031 or 4895, at 40 grains per shot, is good for 175 rounds, the equivalent of nearly nine 20-rounds boxes.

With a "reserve stockpile" of a couple of pounds of the powder(s) you need, a few thousand primers stashed away in a safe place against a rainy day, you can "pay as you go" with new component purchases, leaving your emergency stock for hard times. Primers and powders properly stored have indefinite shelf life; with care cases can be reloaded many times. This tactic will ensure that if and when there are major shortages (or new restrictions on ammunition purchases are imposed) you can continue to shoot.

Everyone knows that primers are the weak link in the chain. Buy enough to ensure you won't run out. You can make your own bullets, and you can almost always get or make cases, but primers are something beyond the level of the reloader. Don't get caught short. You can never have too many primers. Don't believe the rumors that "...the government requires primers to have a short shelf life..." First of all, this isn't technically possible with current priming mixes; and second, no such law exists (yet).

The second strategy is to shoot cast bullets instead of jacketed ones whenever possible. Cast bullets, even when purchased from commercial sources, are significantly cheaper than jacketed ones, entirely suited to 99% of shooting needs, and much, much gentler on gun barrels. Better still, with a little more kit you can make your own cast bullets almost for free and become independent of commercial sources.

Lead scrap can still be found in junkyards and even on Internet sites. Prices have risen in recent years but lead is still affordable and reasonably available. If you're in a shooting club, scrounging fired bullets from the range's backstop is surprisingly easy and costs nothing. Doing so can even be construed as doing the club a favor in "lead cleanup." Fifteen minutes' time with a large coffee can will get enough high grade lead to make hundreds of bullets, rapidly repaying the cost of a mold and the minimal equipment needed: lead can be used to make bullets for anything from a .25 ACP to a .458 Winchester, at only the price of the electricity to melt it. Scrap lead these days is selling for about $1-2 a pound. One pound will make forty-four 158-grain bullets in .38 or 9mm (2 to 4 cents each), or thirty 230-grain bullets for a .45 (3 to 6 cents each). If you get your scrap for nothing, the only cost is the electricity or gas to melt the lead.

Lead scrap can still be found in junkyards and even on Internet sites. Prices have risen in recent years but lead is still affordable and reasonably available. If you're in a shooting club, scrounging fired bullets from the range's backstop is surprisingly easy and costs nothing. Doing so can even be construed as doing the club a favor in "lead cleanup." Fifteen minutes' time with a large coffee can will get enough high grade lead to make hundreds of bullets, rapidly repaying the cost of a mold and the minimal equipment needed: lead can be used to make bullets for anything from a .25 ACP to a .458 Winchester, at only the price of the electricity to melt it. Scrap lead these days is selling for about $1-2 a pound. One pound will make forty-four 158-grain bullets in .38 or 9mm (2 to 4 cents each), or thirty 230-grain bullets for a .45 (3 to 6 cents each). If you get your scrap for nothing, the only cost is the electricity or gas to melt the lead.

Let's consider as an example the cost of shooting a .38 Special or 9mm. Both calibers can be found in stores, but who knows when the next spasm of panic buying or government-sponsored oppression will put them in the "nearly impossible to obtain" category?

Using cast bullets, most expensive part of a complete reloaded round will usually be the primer, currently running at roughly 4 cents apiece. If you use pick-up brass (it really is amazing how many generous people leave perfectly good brass on the ground at public shooting ranges) you pay nothing for it: even if you're using brass from factory ammunition you bought, every time you reload it the cost of the case is amortized a bit until finally it's paid for. At $25 per pound, and 7000 grains to a pound, a 5-grain charge of Unique is less than 2 cents. You can shoot most pistol calibers for maybe 5 cents per shot or $2.50 per box. That's about the normal price for a fifty-round box of .22 LR. Cast bullet 9mm ammunition costs about the same as a .22, right at the moment. The old idea that .22's were so cheap anyone could afford to burn it up in huge amounts has been stood on its head.

The same logic applies to all handgun calibers. Less popular calibers are worth thinking about as alternatives, especially for those who own revolvers. Two good examples are the .44 Special and the .45 Colt (Long), but there are others. Most of these "obsolete" calibers are outstanding self-defense choices (which is what they were originally intended for) and components can be purchased or made easily.

What about rifle ammunition? At $25 a pound for most rifle powders each 40 grain charge costs 14  cents. Brass for common calibers like .30-06, .308, and .270 isn't expensive (and is often free for the asking). A hundred cases will keep most shooters and almost all hunters in business for years. In a cast bullet reload you typically use less powder than for a jacketed bullet, so let's knock that 14 cents down to a dime; add a 4-cent primer, free brass and a free bullet. Eighteen cents per round: 20 rounds for less than $4. Try finding centerfire rifle ammunition in stores at that price! Plus you would be independent of commercial supplies that might well be the target of Big Brother's (or, God help us, Big Sister's) inevitable push after a bad election year.

cents. Brass for common calibers like .30-06, .308, and .270 isn't expensive (and is often free for the asking). A hundred cases will keep most shooters and almost all hunters in business for years. In a cast bullet reload you typically use less powder than for a jacketed bullet, so let's knock that 14 cents down to a dime; add a 4-cent primer, free brass and a free bullet. Eighteen cents per round: 20 rounds for less than $4. Try finding centerfire rifle ammunition in stores at that price! Plus you would be independent of commercial supplies that might well be the target of Big Brother's (or, God help us, Big Sister's) inevitable push after a bad election year.

Compare home-made cast bullets to the price of the very good commercial ones and you will see that casting equipment pays itself off rapidly: a brand new bullet mold is about $20, a lead pot for the top of a stove less than $15, and the rest of the kit might run $20-25 in the aggregate. A couple of casting runs will amortize your total costs, and the rest is "profit" on your "investment." Cast bullets allow plenty of recreational shooting and practice for minimal cost.

Nor should cast bullets be ignored by hunters. There is no animal in North America that can't be—and hasn't been—hunted with cast bullets, and they're suitable for the whitetail deer most of us pursue. If you know what you're doing and have some patience, your home-made bullets will shoot as well or better than commercial ones of any type. Many good manuals on how to "roll your own" are available and the technology involved is downright primitive.

The real issue for hunters may be the on-going war against lead. It is already illegal to use lead bullets on game in California, and other states may well pass similar laws. In such a case each individual must decide how—and whether—to comply with such restrictions.

The third strategy is a bit more difficult to pull off and can in some cases depend on the previous two: shoot calibers that are less popular, and much less in demand. Reloading gear is available for any caliber imaginable, no matter how outré. Some are familiar to shooters, others less so, but they all "work." Virtually any rifle or pistol caliber that has been issued to any army, anywhere in the world, can be used as a hunting or self-defense round.

The incomparable .45-70 (the oldest centerfire rifle round in continuous production) is eminently suited to reloading. It's perfectly suited to cast bullets, and even in today's marketplace cases and other components are easy to get. The old time buffalo hunters used the .45-70 to wipe out whole herds—using lead bullets they cast over campfires. The .30-40 Krag is no slouch as a hunting round, either, and while it's still loaded by US companies, it has a small following and can be found with a little looking. Molds for .30 caliber bullets are available from several makers. Neither of these calibers is as popular as it was at one time, and both are pretty readily available.

American shooters are familiar with common European military rounds, such as 8mm Mauser and .303 British. Military surplus ammunition in these calibers has pretty much dried up and the various hostile administrations have diligently been working to cut off imports. Nevertheless, these two calibers, among others, are made commercially for sporting use by both US and foreign companies. Both and many other ex-military calibers (e.g., 7.62x39 and 7.62x54R) are suitable for hunting in North America. Even the humble 6.5x52 Carcano is a fine deer and bear round; the 8x57mm Mauser will do anything a .30-06 will. The .303 British is about equivalent to the .30-40 Krag. The 7.62x39 is in the .30-30 class and the 7.62x54R is pretty much equivalent to the .308 Winchester in performance. All of these can be loaded with cast bullets, although commercial jacketed ones are also available.

American shooters are familiar with common European military rounds, such as 8mm Mauser and .303 British. Military surplus ammunition in these calibers has pretty much dried up and the various hostile administrations have diligently been working to cut off imports. Nevertheless, these two calibers, among others, are made commercially for sporting use by both US and foreign companies. Both and many other ex-military calibers (e.g., 7.62x39 and 7.62x54R) are suitable for hunting in North America. Even the humble 6.5x52 Carcano is a fine deer and bear round; the 8x57mm Mauser will do anything a .30-06 will. The .303 British is about equivalent to the .30-40 Krag. The 7.62x39 is in the .30-30 class and the 7.62x54R is pretty much equivalent to the .308 Winchester in performance. All of these can be loaded with cast bullets, although commercial jacketed ones are also available.

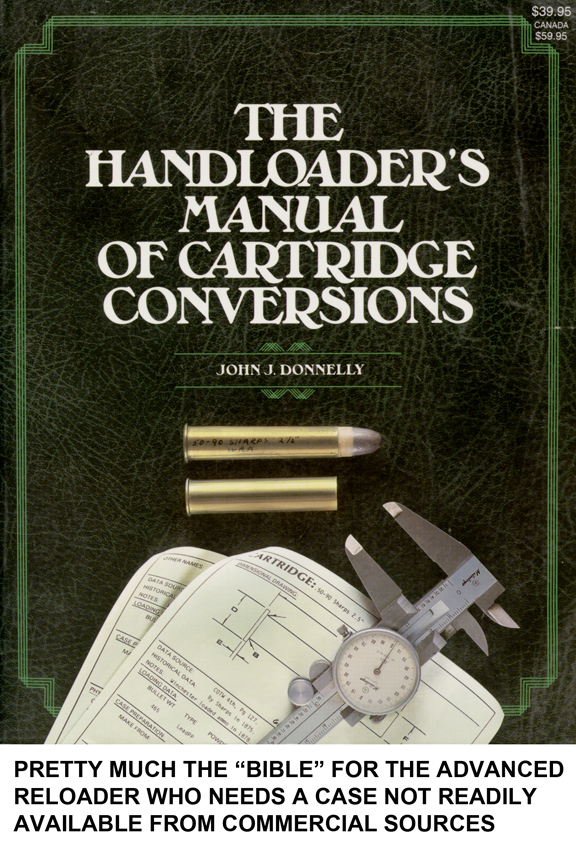

You can actually make cases for some less popular calibers from common ones. Some conversions are easy, some are not, but if you're creative and enjoy a challenge, with the right equipment and motivation it's possible to get virtually any rifle to go BANG! I've made ammunition in such obscure sizes as 10.4x38R Vetterli, 8x60R Kropatschek, 9.4 Dutch, and .577 Snider. A manual of cartridge conversion protocols will provide guidance and specific instructions. Some of the easy ones: the 7mm-08 is nothing more than an altered .308 Winchester case; the .270 can be made from .30-06, as can 8x57, just to name some examples. Almost any imaginable case can be made up from something else if you want to make the effort.

You can actually make cases for some less popular calibers from common ones. Some conversions are easy, some are not, but if you're creative and enjoy a challenge, with the right equipment and motivation it's possible to get virtually any rifle to go BANG! I've made ammunition in such obscure sizes as 10.4x38R Vetterli, 8x60R Kropatschek, 9.4 Dutch, and .577 Snider. A manual of cartridge conversion protocols will provide guidance and specific instructions. Some of the easy ones: the 7mm-08 is nothing more than an altered .308 Winchester case; the .270 can be made from .30-06, as can 8x57, just to name some examples. Almost any imaginable case can be made up from something else if you want to make the effort.

Would oddball calibers like these be ideal replacements for modern ones? Not hardly, but when some of the "normal" stuff seems to be made of Unobtanium, they will work. It's even possible to reload some rimfire calibers and pinfire ammunition, if you're willing to invest in some special equipment. This is "advanced reloading" but it isn't rocket science and anyone can do it.

Two More Options: Air Rifles And Muzzle-Loaders

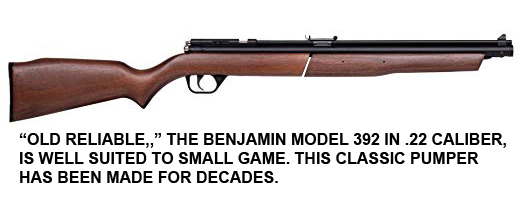

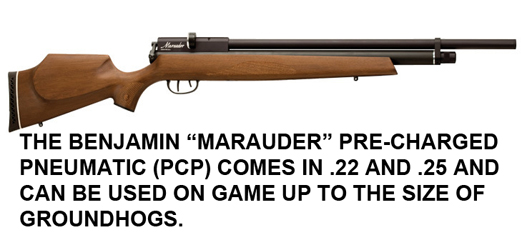

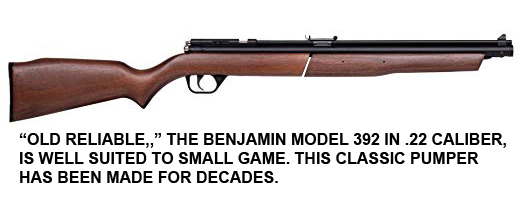

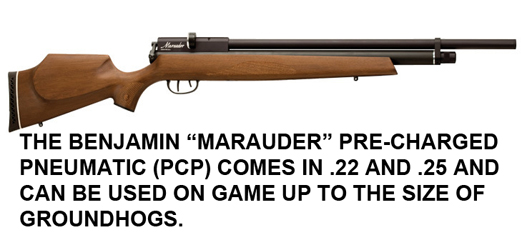

Without going into detail in this already over-long essay, it's worth pointing out that for the casual plinker and shooter, the new generation of air rifles and/or pistols offer many fine choices to replace the .22 LR as a "fun gun." Furthermore, a good air rifle is perfectly suited to hunting small game. Air rifles are made in calibers from .17 to .50 and some of the large-bore guns can even be used on deer-sized animals. Nor are shotgunners left out: several air-powered shotguns suited to small game are available. The technicalities of air guns are too complex to be dealt with here, but anyone interested in them should check out what's on offer at Pyramyd Air or Airgun Depot. Both companies also will give sound advice and instructions, gratis.

Airguns have several advantages. First, they're are mostly unregulated in the USA, so can be purchased without any hoo-hah from the government; and more often than not they're permissible in places where firearms are not. Another, especially in terms of the war on lead, is that pellet manufacturers produce lead-free projectiles. These are lighter and harder than lead ones, and can be very effective: I've seen a video of feral hogs being killed with a small-caliber air rifle using non-lead pellets. A stunt, to be sure, but it makes the point that these rifles aren't kids' toys, they're real guns.

Some examples, all USA-made:

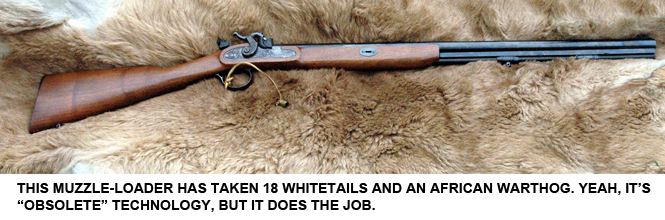

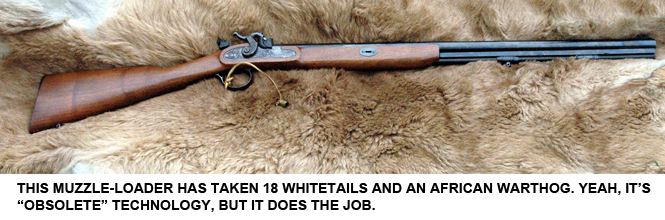

Muzzle-loaders have long had a solid presence in the American sporting gun market. Hunters using them take every North American game species on a regular basis. "Modern" in-line muzzle-loaders dominate the market but the old-style sidelock guns, which may be "obsolete" technology, work just as well today as they did in the days of Lewis and Clark. Once again, at present except in a few jurisdictions muzzle-loaders are unregulated and can be purchased freely. While lead projectiles are most widely used in muzzle-loaders, some companies, bowing to pressure from the Eco-Nazis, are now making lead-free ones.

It Ain't Over Till It's Over

We have been there before; we will be there again. During the Second World War, long before the current savage persecution and demonization of gun owners began, at a time when everyone (even in Congress) understood that the Second Amendment means exactly what it says, a time when guns were very much in the mainstream of American life, the US was faced with a complete cessation of all production of sporting ammunition for civilian use. That shut-off was indefinite, "for the duration," and in the end it lasted for five years. The shooting community survived the famine through careful and thoughtful use of what supplies were available. We can—we must—do that again.

Hang Together Or We Will All Hang Separately

Today's shooting community faces a far more hostile political and social environment than was true 50 years ago. The most important strategy of all to deal with it is solidarity. Ammunition shortages ease in time, all the sooner if we accept an individual responsibility to use resources as wisely as people did 75 years ago. But there is more to it than that: we have to think of the future. There will be more—and worse—crises, including more shortages, after this moment is past. Take heed, and prepare now for the dark days that are coming.

We have won major victories in the Supreme Court and at the state levels in the past 10 years, but far from discouraging our enemies these wins have only infuriated them and made them vow to try even harder to deprive us of our rights. There are some who think the ammunition shortage is a result of a decision by our enemies to strike at the ammunition supply, thereby rendering firearms "useless" and there may be some truth to that belief. This idea was put forward years ago by some of the anti-gun crowd, and it's been recently revived, using the truly insane argument that "There may be a 'right to keep and bear arms,' but the Heller and McDonald decisions didn't say anything about restricting ammunition!" Shooters and hunters can't become complacent. Anti-gun people are essentially religious fanatics who see themselves on a holy crusade: they will never give up and they will never go away.

But they cannot win if we stand together and think of ways to foil their schemes. Learn to reload; stockpile supplies of ammunition and components; make do with what you have; use what you have prudently and effectively. If your buddy needs help you can give, give it to him. Collect brass even for calibers you don't shoot: someone who does may have something that you need. Establish support networks. Be willing to teach what you learn. Watch the politicians, never trust them, and never, ever, take your eyes off the anti-gun movement. We get blind-sided when we get complacent, as we did in 1968.

Support the principled efforts of the organizations fighting them, and if you are not now a member, JOIN THE NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION, your state association, and any other pro-gun organizations you find congenial.

Support the principled efforts of the organizations fighting them, and if you are not now a member, JOIN THE NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION, your state association, and any other pro-gun organizations you find congenial.

Become a teacher: a Hunter Education or NRA Instructor is a powerful role model. You can show people who are "on the fence" the truth. Every time a hesitant woman is talked into taking a handgun safety class by her husband or boyfriend and has a positive experience, we gain an ally. Every time a mother who is unsure she likes the idea of her child hunting sits in on a Hunter Ed class and sees that hunters and shooters stress safety and responsibility, we gain an ally. Every time a youngster is safely introduced to shooting as a sport, we make an ally. Every time a Boy Scout gets a Merit Badge in Rifle or Shotgun, we gain an ally. If we commit to our Cause and to advancing it, we will win.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |

It's no secret that at times certain calibers of ammunition have been difficult, and at times impossible, to find. Two recent examples: a couple of years ago, it was nearly impossible to locate .380 ACP, and at times .22 Long Rifle ammunition has been as scarce as frog hair. There are various reasons for these two occurrences and not a few theories about conspiracies on the part of the government, industry, or both, bringing them about.

It's no secret that at times certain calibers of ammunition have been difficult, and at times impossible, to find. Two recent examples: a couple of years ago, it was nearly impossible to locate .380 ACP, and at times .22 Long Rifle ammunition has been as scarce as frog hair. There are various reasons for these two occurrences and not a few theories about conspiracies on the part of the government, industry, or both, bringing them about.  But to be honest, a fair bit of the problem with sporadic shortages can properly be laid at the feet of anti-gun politicians and in particular the (now thankfully ended) Obama administration, the most anti-gun in US history (so far). Obama's BATF restricted imports of many popular calibers on the grounds that they're used in "assault weapons" and stopped any importation of ammunition from Russia, excusing this blatantly anti-gun action as part of the "economic sanctions" imposed after the invasion of Ukraine. Nevertheless, if the government had somehow deliberately caused the shortages—and I'm sure the Obama Administration would have been happy to do so if they could have—the most affected calibers would be .223, .308, and 9mm Parabellum, not .22's.

But to be honest, a fair bit of the problem with sporadic shortages can properly be laid at the feet of anti-gun politicians and in particular the (now thankfully ended) Obama administration, the most anti-gun in US history (so far). Obama's BATF restricted imports of many popular calibers on the grounds that they're used in "assault weapons" and stopped any importation of ammunition from Russia, excusing this blatantly anti-gun action as part of the "economic sanctions" imposed after the invasion of Ukraine. Nevertheless, if the government had somehow deliberately caused the shortages—and I'm sure the Obama Administration would have been happy to do so if they could have—the most affected calibers would be .223, .308, and 9mm Parabellum, not .22's.  The first strategy is simple and obvious: reload your ammunition.

The first strategy is simple and obvious: reload your ammunition.  Lead scrap can still be found in junkyards and even on Internet sites. Prices have risen in recent years but lead is still affordable and reasonably available. If you're in a shooting club, scrounging fired bullets from the range's backstop is surprisingly easy and costs nothing. Doing so can even be construed as doing the club a favor in "lead cleanup." Fifteen minutes' time with a large coffee can will get enough high grade lead to make hundreds of bullets, rapidly repaying the cost of a mold and the minimal equipment needed: lead can be used to make bullets for anything from a .25 ACP to a .458 Winchester, at only the price of the electricity to melt it. Scrap lead these days is selling for about $1-2 a pound. One pound will make forty-four 158-grain bullets in .38 or 9mm (2 to 4 cents each), or thirty 230-grain bullets for a .45 (3 to 6 cents each). If you get your scrap for nothing, the only cost is the electricity or gas to melt the lead.

Lead scrap can still be found in junkyards and even on Internet sites. Prices have risen in recent years but lead is still affordable and reasonably available. If you're in a shooting club, scrounging fired bullets from the range's backstop is surprisingly easy and costs nothing. Doing so can even be construed as doing the club a favor in "lead cleanup." Fifteen minutes' time with a large coffee can will get enough high grade lead to make hundreds of bullets, rapidly repaying the cost of a mold and the minimal equipment needed: lead can be used to make bullets for anything from a .25 ACP to a .458 Winchester, at only the price of the electricity to melt it. Scrap lead these days is selling for about $1-2 a pound. One pound will make forty-four 158-grain bullets in .38 or 9mm (2 to 4 cents each), or thirty 230-grain bullets for a .45 (3 to 6 cents each). If you get your scrap for nothing, the only cost is the electricity or gas to melt the lead.  cents. Brass for common calibers like .30-06, .308, and .270 isn't expensive (and is often free for the asking). A hundred cases will keep most shooters and almost all hunters in business for years. In a cast bullet reload you typically use less powder than for a jacketed bullet, so let's knock that 14 cents down to a dime; add a 4-cent primer, free brass and a free bullet. Eighteen cents per round: 20 rounds for less than $4. Try finding centerfire rifle ammunition in stores at that price! Plus you would be independent of commercial supplies that might well be the target of Big Brother's (or, God help us, Big Sister's) inevitable push after a bad election year.

cents. Brass for common calibers like .30-06, .308, and .270 isn't expensive (and is often free for the asking). A hundred cases will keep most shooters and almost all hunters in business for years. In a cast bullet reload you typically use less powder than for a jacketed bullet, so let's knock that 14 cents down to a dime; add a 4-cent primer, free brass and a free bullet. Eighteen cents per round: 20 rounds for less than $4. Try finding centerfire rifle ammunition in stores at that price! Plus you would be independent of commercial supplies that might well be the target of Big Brother's (or, God help us, Big Sister's) inevitable push after a bad election year.  American shooters are familiar with common European military rounds, such as 8mm Mauser and .303 British. Military surplus ammunition in these calibers has pretty much dried up and the various hostile administrations have diligently been working to cut off imports. Nevertheless, these two calibers, among others, are made commercially for sporting use by both US and foreign companies. Both and many other ex-military calibers (e.g., 7.62x39 and 7.62x54R) are suitable for hunting in North America. Even the humble 6.5x52 Carcano is a fine deer and bear round; the 8x57mm Mauser will do anything a .30-06 will. The .303 British is about equivalent to the .30-40 Krag. The 7.62x39 is in the .30-30 class and the 7.62x54R is pretty much equivalent to the .308 Winchester in performance. All of these can be loaded with cast bullets, although commercial jacketed ones are also available.

American shooters are familiar with common European military rounds, such as 8mm Mauser and .303 British. Military surplus ammunition in these calibers has pretty much dried up and the various hostile administrations have diligently been working to cut off imports. Nevertheless, these two calibers, among others, are made commercially for sporting use by both US and foreign companies. Both and many other ex-military calibers (e.g., 7.62x39 and 7.62x54R) are suitable for hunting in North America. Even the humble 6.5x52 Carcano is a fine deer and bear round; the 8x57mm Mauser will do anything a .30-06 will. The .303 British is about equivalent to the .30-40 Krag. The 7.62x39 is in the .30-30 class and the 7.62x54R is pretty much equivalent to the .308 Winchester in performance. All of these can be loaded with cast bullets, although commercial jacketed ones are also available.  You can actually make cases for some less popular calibers from common ones. Some conversions are easy, some are not, but if you're creative and enjoy a challenge, with the right equipment and motivation it's possible to get virtually any rifle to go BANG! I've made ammunition in such obscure sizes as 10.4x38R Vetterli, 8x60R Kropatschek, 9.4 Dutch, and .577 Snider. A manual of cartridge conversion protocols will provide guidance and specific instructions. Some of the easy ones: the 7mm-08 is nothing more than an altered .308 Winchester case; the .270 can be made from .30-06, as can 8x57, just to name some examples. Almost any imaginable case can be made up from something else if you want to make the effort.

You can actually make cases for some less popular calibers from common ones. Some conversions are easy, some are not, but if you're creative and enjoy a challenge, with the right equipment and motivation it's possible to get virtually any rifle to go BANG! I've made ammunition in such obscure sizes as 10.4x38R Vetterli, 8x60R Kropatschek, 9.4 Dutch, and .577 Snider. A manual of cartridge conversion protocols will provide guidance and specific instructions. Some of the easy ones: the 7mm-08 is nothing more than an altered .308 Winchester case; the .270 can be made from .30-06, as can 8x57, just to name some examples. Almost any imaginable case can be made up from something else if you want to make the effort.