This original version of this essay appeared in the 2012 edition of Gun Digest

The origins of the famous gunmaking firm of Webley date to 1827, when 14-year-old Philip Webley was apprenticed to the Birmingham gunmaker William Davis. Davis died in 1831 and his daughter Caroline and her mother carried on the firm’s business. Upon completing his apprenticeship in 1834, Philip went into partnership with his brother James as a “percussioner and gun lock maker,” and in what was probably an inevitable development, in 1838 he followed

a time-honored tradition: he married his former boss’s daughter. The Webley brothers had  prospered and by 1840 they were making (among other things) gun implements for the Crown

and for the East India Company. They had done so well, in fact, that by 1845 Philip was able to

buy out the assets of the Davis firm run by his wife and his mother-in-law, and take his late

father-in-law’s place in the Birmingham gun trade as an independent maker.

prospered and by 1840 they were making (among other things) gun implements for the Crown

and for the East India Company. They had done so well, in fact, that by 1845 Philip was able to

buy out the assets of the Davis firm run by his wife and his mother-in-law, and take his late

father-in-law’s place in the Birmingham gun trade as an independent maker.

In the 1850’s Britain was a big market for firearms and Birmingham was the center of

production. Strong-jawed Builders Of The Empire bringing the Queen’s Rule to India, Africa,

and the wilds of Canada needed guns; so did explorers and even missionaries risking life and

limb in the fetid jungles of the Dark Continent. So too did the considerable numbers of domestic

customers who lived in a society plagued by crime but lacking an effective police force. Philip

Webley did business at the upper end of the market, producing high-quality firearms that quickly cemented his reputation as one of Birmingham’s best gunsmiths.

In 1857, Sam Colt made a business decision that transformed the British market: he closed his factory in England, creating an opening for domestic firms to serve the growing domestic market with less expensive mass-produced guns. Webley was well positioned to seize this opportunity. He had been working steadily to adapt the “American method” of standardized production using interchangeable parts and was ahead of many of his competitors. The years after 1860 saw the expansion of his trade to include more civilian sales and the development of popular new product lines. Many of Webley’s most famous solid-frame revolver designs were introduced from 1860 onwards, including the Royal Irish Constabulary series, the widely-imitated “British Bulldog,” and the Metropolitan Police series adopted by Scotland Yard. Webley’s leadership of the field was undisputed.

Then as now the Holy Grail of any arms-making firm was getting the Army to adopt its products. A lucrative military contract eluded Webley for years, and despite his success with police and

civilian sales it would not be until 1887 that Webley won a contract to provide a revolver for

general Army service: the Mark I, first of the long series of military top-breaks that would serve

the Crown until well after World War 2.

But Webley had forged ahead with refinement of the top-break concept, gradually perfecting it. The firm held numerous patents on ejector designs, breech-closing devices, and internal lockwork mechanisms, all of them steadily improving performance and reliability. Simultaneously Webley developed methods to reduce unit cost with improved methods of manufacture. He was very savvy about customer service as well, happily providing small shops

with “private label” guns marked to order. All of these production and marketing innovations

kept the company’s name at the front of the pack and solidified its reputation for solid, utterly reliable, and very accurate weapons. Among the technical innovations was one of importance that would be used in all the firm’s subsequent top-break designs: the stirrup breech catch, covered by British patent #4070 of 1885. It provided a locking system that made the top-break as strong as any solid frame design. It was one of the features that convinced the Army to adopt

the Mark I.

The officers of Her Majesty’s forces in those days were drawn from the upper crust of British society. As befitted an institution that was part of a culture resting on class distinctions the Army drew a well-defined line between the enlisted “rankers” drawn from the Lower Orders and the Gentlemen who commanded them. It was standard practice among the gentry and the nobility to send off at least one of their sons into a military or naval career. An officer’s pay was nowhere near enough to meet the financial demands placed on a gentleman, who after all had a place in Society to uphold; but most if not all of them had private means (in the form of an allowance from the family or income from estates) that was adequate for the expenses of military service. Upon graduation from the military academy at Sandhurst, a newly commissioned Subaltern “kitted out” for active service at his own expense. Among the items he was required to buy was his sidearm.

With the adoption of the Mark I as official issue in 1887, Webley gained a reputation among the officers of the Queen’s Army as the “official” gun maker. This gave the firm an “in” to the niche market of privately-purchased officer’s sidearms. In the early 1880’s, Webley had brought out a new series of target revolvers incorporating simultaneous ejection of spent cartridges and the strong stirrup breech lock initially developed by Edwinson C. Green. The “Webley-Green” or “W-G” target guns were perhaps not only the most finely crafted revolvers ever made, representing Victorian-era workmanship at its absolute zenith, they were exceptionally accurate and found great favor with target shooters.

The Field ( the leading shooting publication of the day) reproduced a target fired by a Mr C. Dixon in

October of 1889, showing one ragged 6-shot hole in a

20-yard bullseye, a level of performance that would be

competitive even today. To increase their appeal to

Army marksmen, the early W-G’s were chambered for the then-standard .476 round used in the

ungainly Enfield Mark I and Mark II revolvers that were still official issue.

The Field ( the leading shooting publication of the day) reproduced a target fired by a Mr C. Dixon in

October of 1889, showing one ragged 6-shot hole in a

20-yard bullseye, a level of performance that would be

competitive even today. To increase their appeal to

Army marksmen, the early W-G’s were chambered for the then-standard .476 round used in the

ungainly Enfield Mark I and Mark II revolvers that were still official issue.

Webley’s status as an official supplier, coupled with the W-G’s reputation for ruggedness and accuracy led the firm to develop a version for use on “active service” in 1892. This was the first of the “W-G Army” models, released in the official caliber of .476. This “Army Model” was produced concurrently with the target versions, and in due time was approved by the Army as a type suitable for officers’ use and private purchase.

Unlike the military top-breaks (Marks I through VI) the “W-G Army” was never official issue, but those who were authorized to carry sidearms and who could afford the best could choose to substitute the W-G Army for the issue weapon of the day. Many officers did, because the W-G was not only sturdy and accurate, it had exceptionally good lockwork in both double and single action modes.

Shooting one of these big guns is a revelation as to just how good a revolver can

be, and the kind of craftsmanship in which Webley’s firm took justifiable pride. The action is as

slick and smooth as could be desired. Even though the huge hammer (with an integral firing pin

that looks as if it could punch holes in an oil drum) has a rather long travel back and a solid

impact when it falls, the pull is clean and even throughout its length. In single action the trigger

is crisp, and if not especially light, is very

consistent from shot to shot. The target

published in The Field is one that an

expert marksman today could still—perhaps—duplicate using one of these

beautifully fitted and polished guns.

Many retailers sold W-G Armies, but the

most prominent of these, certainly the

most important one for Army officers,

was the Army & Navy Cooperative

Society, Ltd. Founded in 1871 by a group

of military and naval officers, its mission

was to supply “articles of domestic

consumption and general use to its

members at the lowest remunerative

rates.” Today's equivalent would be the Post Exchange.

Many retailers sold W-G Armies, but the

most prominent of these, certainly the

most important one for Army officers,

was the Army & Navy Cooperative

Society, Ltd. Founded in 1871 by a group

of military and naval officers, its mission

was to supply “articles of domestic

consumption and general use to its

members at the lowest remunerative

rates.” Today's equivalent would be the Post Exchange.

The “Army & Navy Store” sold, among many other things, all the items an officer needed, including household goods, fishing tackle, and guns for service and sport. The CSL was a major outlet for Webley’s production. W-G Armies sold through them are marked on the barrel rib.

The “W-G Army” went through several minor variations, all of which were popular with officers, and deservedly so. They were powerful, accurate, and durable. They fit perfectly in the holsters issued for use with the Marks I though VI. The Army Models had 6-inch barrels and fixed sights, could be had with either birds-head grips or flared “target” style ones; and would fire the standard military issue round. With the adoption of the Mark I, the Army switched over to the first of several variations of what is now called the “.455 Webley” round. The W-G would of course shoot this caliber as well, so that an officer who’d equipped himself with an earlier W-G Army had no problems and didn’t have to buy another gun. Many post-1891 W-G Armies are stamped “.455/.476” to indicate the fact that whatever was on hand in the remote outposts to which an officer might be sent could be used.

Though not so well-known as the “issue” Webley top-breaks, especially the Mark VI used in both World Wars, the W-G Army provided sterling service to the Crown throughout its production life, and for long afterwards. And not only to the Army: The Bank of England and the Union Steamship Company are two commercial firms known to have purchased W-G’s in quantity for use by their staffs.

The target versions won many medals at the annual Bisley competition, and were highly favored by the “name” shooters of the day such as the American

Olympic medallist, Walter Winans (1852-1920), author of The Art of Revolver Shooting.

Never “official,” but always faithful and reliable, the W-G Army soldiered on for many years

after production ceased. The total number of each variation made and the exact date when the

line was discontinued isn’t easy to determine, but W-G Armies were certainly made at least as

late as 1897: many specimens are marked “W. & S. Ltd” and the firm

name “Webley & Scott” came into

existence in that year.

Never “official,” but always faithful and reliable, the W-G Army soldiered on for many years

after production ceased. The total number of each variation made and the exact date when the

line was discontinued isn’t easy to determine, but W-G Armies were certainly made at least as

late as 1897: many specimens are marked “W. & S. Ltd” and the firm

name “Webley & Scott” came into

existence in that year.

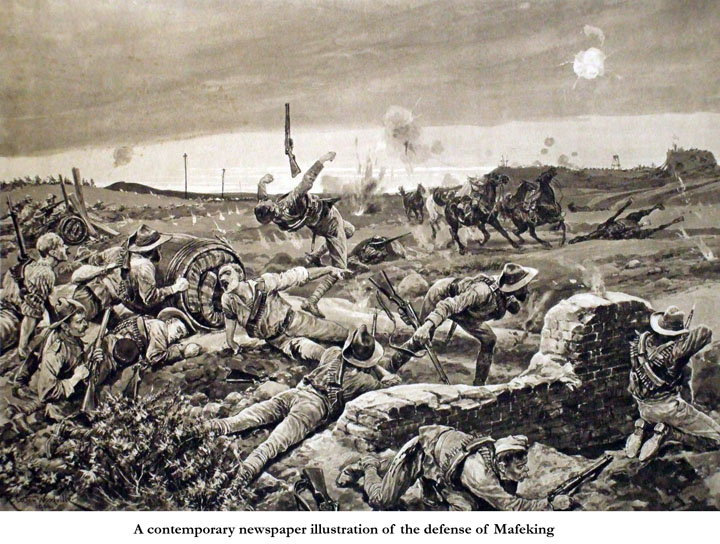

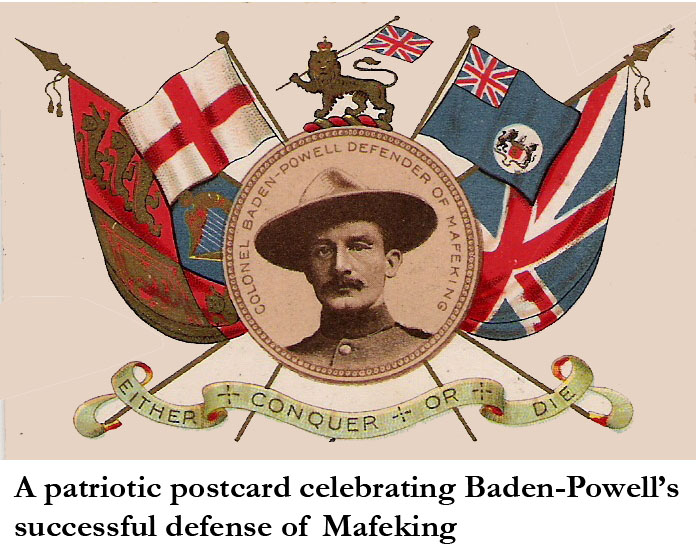

Some references imply without so stating that W-G’s in various configurations were made at least as late as 1904, carrying production through the Boer War. This seems highly likely. That conflict was Britain’s largest up to that time and the Army greatly increased in size. The W-G was highly popular with officers in the Boer War: many of them can still be found in South African gun shops. It's probable that production of the W-G’s ceased no later than 1914, with Britain’s entry into World War One and the need to ramp up production of the Mark V and later the Mark VI standard-issue revolvers. Since Webley’s pre-1945 production and sales records have been badly fragmented (and mostly destroyed) by two wars, a major fire, and the Blitz, it’s not really possible to reconstruct the history of any specific W-G Army with any accuracy. But given the small size of the British Army in the late 19th Century, and its involvement in several small and large wars after 1887, the likelihood that any officer’s sidearm was carried into combat and probably “fired in anger” is very high. Even so august a personage as Lord Baden-Powell, the heroic General who commanded British forces at the Siege of Mafeking, preferred to wear a W-G Army at his side.

A W-G Army manufactured in 1892 that belonged to a career officer

could very easily have ascended the Nile in the River War against the Mahdi in 1896; and would

almost certainly have been used in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. I once

A W-G Army manufactured in 1892 that belonged to a career officer

could very easily have ascended the Nile in the River War against the Mahdi in 1896; and would

almost certainly have been used in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. I once  owned a

CSL-marked gun that had come to me from a South African shop; one of those “I wish it could

talk!” guns that you know had a tale or two to tell. Depending on the age of its original

purchaser, a W-G could well have seen trench service in the First World War as well. Given that

these finely crafted weapons were valued possessions, a retired officer might even have passed

on his trusty old “defender” to a son serving in World War Two.

owned a

CSL-marked gun that had come to me from a South African shop; one of those “I wish it could

talk!” guns that you know had a tale or two to tell. Depending on the age of its original

purchaser, a W-G could well have seen trench service in the First World War as well. Given that

these finely crafted weapons were valued possessions, a retired officer might even have passed

on his trusty old “defender” to a son serving in World War Two.

Some W-G's were imported to the USA in the halcyon years before 1968 and sold on the surplus market. Some unfortunately were mutilated by having the cylinder turned to shoot .45 ACP in half-moon clips (a very bad idea for a gun proved with black powder!) but most have not. If one is marked “.455/.476” it will accept the .45 Colt Long and shoot “Cowboy Action” loads safely so there is no need for this to be done if you are lucky enough to come across one of these beautiful relics of a bygone age.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |