My wife and I recently returned from a three-week trip to Scotland hitting the highlights of two major cities (Edinburgh and Glasgow) and touring the Highlands by car. We saw and did a great deal. In addition to seeing the sights I was able finally to meet face-to-face with two gentlemen with whom I've communicated by e-mail for years, Ian G. and Kim S. Both went out of their way to make us welcome.

We flew out of Dulles Airport via Dublin on Aer Lingus, the Irish national airline. Things didn't start auspiciously: we were delayed on the tarmac for 2-1/2 hours past our nominal take-off time, thanks to bad weather along the planned route. I have a policy of sleeping through long airplane flights, and promptly conked out as soon as we boarded, but I was forced to sit in an aisle seat so I was periodically awakened by the screeching of infants, the passage of people on the way to the lavatories, and the bonking my knee received from the drinks cart rumbling up and down. I will say this for Aer Lingus: though we missed our original connecting flight from Dublin to Edinburgh, they had prepared boarding passes for us in advance so that boarding the replacement flight was a breeze.

Ireland is in the European Union, as is the UK (so far), so as we entered Dublin our passports were stamped "IT to UK" which was all well and good; but three weeks later when we left, again via Dublin, our passports were not stamped as having exited the EU. The UK didn't stamp them at all in either direction. I suppose that therefore we're technically still "in" the EU—and sooner or later we'll have overstayed our "visas." What will happen after Brexit takes place is anyone's guess.

For the most part we stayed in Bed-And-Breakfast places, which in Europe are far cheaper than hotels; furthermore in some small places hotels simply don't exist. Mostly these were very nice places (with one glaring exception, see below). I'm not a fan of B&B's, much preferring the sterile anonymity of a decent hotel to the "atmosphere" of a B&B. In a B&B you almost feel bad pointing out that there's no hot water or that the sheets could really have used another go-round in the laundry. Moreover, most B&B's are basically adapted from private homes. They never have elevators and we always get put into a room several flights up a winding stairway. Dragging luggage up and down is no fun but it's part of the B&B experience. So is living out of a suitcase.

We stayed in real hotels in Edinburgh and a sort-of-hotel in Glasgow.

EDINBURGH

No one in his right mind would drive a car in Edinburgh if he could avoid doing so and we didn't try. Nor did we need to. Our hotel, The Motel One (it's a German chain and it isn't a "motel" in the American sense) was only a hundred yards from the Waverley Bridge train station, a little more to the main shopping district on Princes Street, and across the street from the depot for garishly painted "Hop-On-Hop-Off" tourist buses that could get us anywhere too far away to walk. Edinburgh also has a reasonably good subway system. The Motel One is within walking distance of Edinburgh Castle, several decent restaurants, and many sites we wanted to visit. It couldn't have been better located for what we wanted to do.

Edinburgh is chock full of stuff to see, but the Number One item on my list was the Royal Yacht, Britannia. One of the perks of being a monarch is that you get to have lots of very expensive toys; and this includes yachts. Nice, big, ocean-going yachts, too, not piddly little sailing vessels.

Having grown up in New York City at the end of the era of great ocean liners, I have always been "into" ships; anything that floats, more or less, floats my boat, so to speak. Give me an opportunity  to board a ship—any ship—and I'm right there. If the ship is a classy one, so much the better; and Britannia is as classy as a ship gets, given her history and purpose.

to board a ship—any ship—and I'm right there. If the ship is a classy one, so much the better; and Britannia is as classy as a ship gets, given her history and purpose.

Britannia was constructed in 1952, the year Elizabeth II became Queen; and went into service in 1953. Her maiden voyage was one in which the Queen and Prince Philip toured the Commonwealth, late that year. Alas, she was decommissioned in 1997 by Tony Blair's penny-pinching Labour government, after 44 years of service during which she steamed a million miles and was the site of nearly a thousand State occasions. Today she's owned by a private foundation, lovingly maintained by volunteers, permanently moored for people to gawk at. She's the main tourist attraction in Edinburgh and rightly so.

In her heyday she had a crew of 256 ratings and 21 officers, all of whom were under orders to be as quiet as possible in carrying out their duties so as not to disturb the Royal Family and their guests: the men wore rubber soled shoes and orders were given by hand signals! Some permissible noise was made by the Royal Marine Bandsmen, whose 26 members played patriotic airs.

The quarters for the Royals were very posh. As well as elegant (separate) bedrooms, formal reception rooms and offices for conducting State business were provided for both the Queen and the Prince; these were fitted up with the latest communications technology, needless to say, so that the affairs of the Empire could be conducted anywhere.

Amenities for the officers were a bit less fancy, but they included a nice wardroom and a lovely bar. Arrangements for the crew were somewhat Spartan, but probably better than they'd have had aboard a warship. A posting to Britannia was a greatly desired one in the Royal Navy, and many members of the crew spent most of a career on board.

Britannia was essentially a floating town, and like any town it had to have medical facilities, including a two-berth sick bay, a dental office, and even an operating theater (excuse me, "theatre"). In addition she was designed to double as a hospital ship in times of need, so the latest medical equipment and supplies were always in stock.

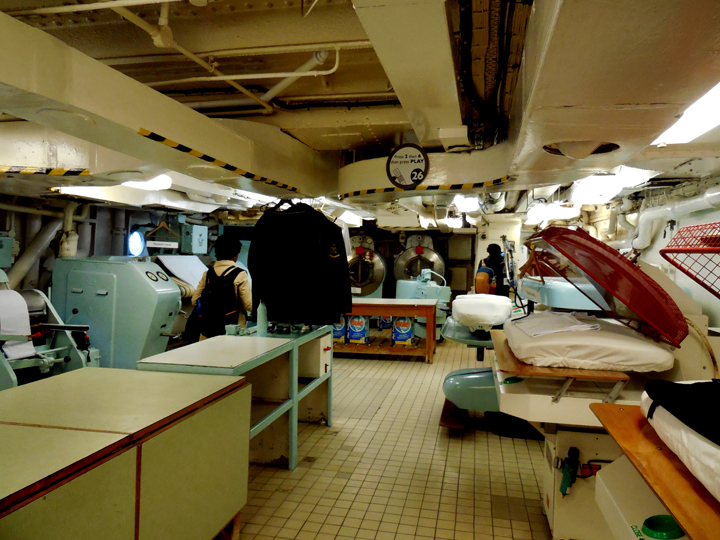

With 256 crew members, 21 officers, many State guests, and the Queen, the Prince, and their family on board, all of whom needed to be looking crisp, clean, and sharp, Britannia maintained an industrial-sized laundry with washing machines, dry cleaning equipment, and machinery to press uniforms to the rigid standards demanded by Royalty.

One of the major drivers Scotland's economy, as everyone knows, is whiskey (Yes, yes, I know it can be spelled without the "e" but it looks wrong to me that way. Since I'm writing this, you get it with the "e" at no extra charge). There are dozens of distilleries scattered around the countryside; a real aficionado of Scotch whiskey can arrange a tour program that includes most (if not all) of them, and have a grand time, even if he can't remember it later. I like Scotch whiskey—it's the only liquor I drink, in fact—but I like it diluted with club soda and a lot of ice. Although my Scottish friends assure me no one would regard this as a perversion, I've met some whiskey snobs here in the USA who recoil in horror at the suggestion. However, on this trip I restricted myself to one tiny sip on a special sort-of tour, a place labeled "The Whisky Experience," right outside the gates of Edinburgh Castle. (Note, I left out the "e" this time.)

One of the major drivers Scotland's economy, as everyone knows, is whiskey (Yes, yes, I know it can be spelled without the "e" but it looks wrong to me that way. Since I'm writing this, you get it with the "e" at no extra charge). There are dozens of distilleries scattered around the countryside; a real aficionado of Scotch whiskey can arrange a tour program that includes most (if not all) of them, and have a grand time, even if he can't remember it later. I like Scotch whiskey—it's the only liquor I drink, in fact—but I like it diluted with club soda and a lot of ice. Although my Scottish friends assure me no one would regard this as a perversion, I've met some whiskey snobs here in the USA who recoil in horror at the suggestion. However, on this trip I restricted myself to one tiny sip on a special sort-of tour, a place labeled "The Whisky Experience," right outside the gates of Edinburgh Castle. (Note, I left out the "e" this time.)

This isn't a distillery, but rather a sort of semi-Disneyland ride in which the patron is seated in a mock barrel and carted through the history and development of the whiskey industry. I learned some things I didn't know from it. It was not until the mid 19th Century that "blended" whiskies existed; prior to that the liquor distilled in different regions had a different character depending on the source of the water and the techniques used to make it. This stuff was what we call today "single malt" whiskey. Now, I don't care for single malts (another heresy, according to some people). I keep it around for guests, but personally I drink "blended" whiskey.

This isn't a distillery, but rather a sort of semi-Disneyland ride in which the patron is seated in a mock barrel and carted through the history and development of the whiskey industry. I learned some things I didn't know from it. It was not until the mid 19th Century that "blended" whiskies existed; prior to that the liquor distilled in different regions had a different character depending on the source of the water and the techniques used to make it. This stuff was what we call today "single malt" whiskey. Now, I don't care for single malts (another heresy, according to some people). I keep it around for guests, but personally I drink "blended" whiskey.

Blended whiskies are made by adding liquor distilled with some grain other than malted barley, and adjusting the single-malt flavor with under-flavors to a specific style. Each distillery has its own special formulae for their blended products, which tend to be much milder than straight single-malts. Master blenders adjust the mixture to create whatever flavor (sorry, flavour) they're after.

Of course part of the tour was an opportunity to sample various styles of whiskey, and it was incumbent upon me to have a wee dram during this part of the tour. What was really interesting in this place was the colossal collection of whiskies: thousands upon thousands of bottles, brands world famous and brands totally obscure. Two rooms full of bottles, all of them un-opened. You can buy Scotch whisky (without the "e") literally anywhere in the country—grocery stores, gas stations, tourist shops, anywhere at all—but that wee dram was all the whiskey I had while I was there.

Another "must-see" place is Edinburgh Castle. As one of the most famous sights in Edinburgh, the Castle is usually thronged with tourists, hordes of them all taking pictures of the same things and of themselves. We have a policy of going to such sites as early as possible, so as to avoid the crowds. By the time we left after a couple of hours we could hardly move through the throngs.

Another "must-see" place is Edinburgh Castle. As one of the most famous sights in Edinburgh, the Castle is usually thronged with tourists, hordes of them all taking pictures of the same things and of themselves. We have a policy of going to such sites as early as possible, so as to avoid the crowds. By the time we left after a couple of hours we could hardly move through the throngs.

Now, when you have seen as many castles as I have, they all tend to look alike, but Edinburgh's version has some special features that made it worth hoofing up almost a mile of a very steep hill (castles are always built on hills, for strategic reasons). One was "Mons Meg," a colossal 15th-Century artillery piece that fired 42-inch cannonballs made of stone.

Another interesting part of the castle was the dog cemetery. The Scots in general are fond of dogs, and unlike in the USA, they're usually welcomed in commercial establishments, pubs, and most other places. Soldiers are also fond of dogs, and Scottish soldiers especially so. I found it very touching to see that a special site had been reserved in the fort to inter their companions and mascots.

On the grounds of the Castle is one very sobering structure: the Scottish National War Memorial. This building is dedicated to the memory of the hundreds of thousands of Scots who fell in the Great War, the Second World War, and subsequent conflicts. Started in the early 1920's, it's not only a shrine but an architecturally and artistically beautiful tribute to those who died. Each regiment has its own section and the names of the dead are inscribed into Rolls of Honour at each station. All the Armed Forces are represented.

Upon entering the Memorial I removed my hat, and was shocked to see that many men did not. Mostly these were young people, and perhaps they might not have known any better. I complained to one of the docents about this and suggested that they ask men to doff their hats on entering. I could hardly believe what I was told in reply: "We understand your concern, sir; and we would like to do so. But we aren't allowed to."

We're museum-goers, my wife and I; and we went to several minor museums dealing with life in Edinburgh at various periods, but the most important museum of all is the National Museum of Scotland, which houses what may well be the most significant museum exhibit anywhere in the world: the taxidermied remains of Dolly the Sheep.

Dolly was the first mammal to be successfully cloned from an adult cell. This may not sound like much to most people, but as a biologist with some knowledge of genetics I'm well aware of how difficult this feat was; and of some of its implications for the future. At one time the idea of cloning animals was the purview of science fiction, but with Dolly it became a very real possibility. Actually, a probability. If an animal as complex as a sheep can be re-created in toto from a single adult cell, then in time any animal can be...including a human. The social and sociological consequences of being able to do this are unpredictable but make no mistake: in time it will happen, if in fact it hasn't already happened in some clandestine laboratory. Cloning mammals opens up a Pandora's box of questions about who should be cloned, when, and why, but not if. In time we'll have to deal with this issue, and Dolly is the humble harbinger of things to come. She may have been just a dumb sheep, but she's also a promise and a warning to mankind.

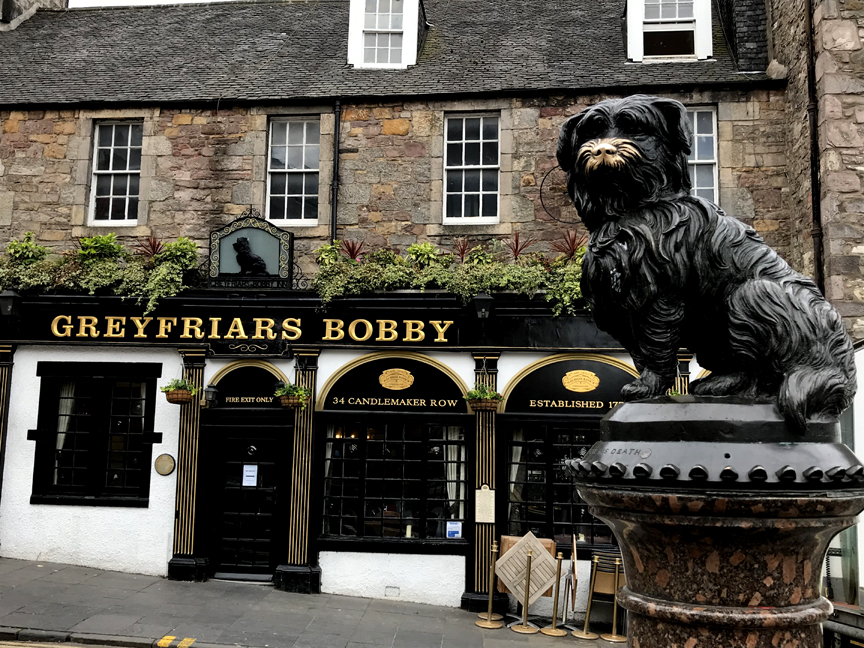

Since my wife and I are Dog People, we had to make a pilgrimage of sorts to the grave and statue of the famous Greyfriars Bobby. Bobby was a terrier who, when his beloved master died, stayed by the grave for the rest of his long life, an outstanding exemplar of the loyalty and devotion of all dogs. When Bobby died he was buried in the outer churchyard of the Greyfriars Kirk; a statue was erected in his honor by a wealthy resident of the city of Edinburgh. There are scurrilous allegations that the story isn't true, that it was a hoax drummed up for commercial reasons. Needless to say, any number of businesses have sprung up in the vicinity that use Bobby's name. All I can say is that if Bobby's story isn't true, it should be.

I mentioned that I had an opportunity to meet with two people with whom I've communicated for a long time as moderator of an Internet discussion group. This group has members from all over the world, including two in Scotland.

I mentioned that I had an opportunity to meet with two people with whom I've communicated for a long time as moderator of an Internet discussion group. This group has members from all over the world, including two in Scotland.

Ian G. graciously took the time came to meet us in Edinburgh. Ian manages a shooting and fishing estate, and he is originally from Northumberland. He brought me a wholly unexpected gift: a mascot bear, named "Norman." Norman too is Northumbrian, and wears his colors proudly. Ian suggested Norman ought to go along on my hunting trips, and so he will! I'm not the least bit superstitious—heavens, no, nobody who hunts could possibly be superstitious—but I have no doubt that having Norman along will bring me nothing but good luck. That's not superstition, it's confidence.

GLASGOW

There was a lot more we did and saw in Edinburgh, but in time we moved on to Glasgow, the largest city in Scotland. We hoofed it down to the Waverley Bridge station and rode one of the numerous trains that leave for Glasgow every day. Upon arrival we checked into the Belhaven Hotel. The location wasn't as perfect as that in Edinburgh, but it was convenient enough. We weren't too far from the subway, and there were two major shopping streets handy in the Kelvingrove area of the West End, quite a nice neighborhood.

The Belhaven was built in the late 19th Century; it's at least five stories tall, one of a row of terraced houses on a quiet side street. Fittings in the walls demonstrated that it was originally lighted by gas.

The Belhaven was built in the late 19th Century; it's at least five stories tall, one of a row of terraced houses on a quiet side street. Fittings in the walls demonstrated that it was originally lighted by gas.

We were told it was originally built as a hotel, but I have my doubts. The rest of the structures on that terrace were unquestionably built as private homes (though of course most of them have long since been divided into flats) so it seems unlikely to me that only one would have been a purpose-built hotel. It's got a winding staircase up all those floors, and predictably we had to schlepp our bags up to our room on the "second" floor. I use quotation marks because in the USA this would be the third floor: we consider the ground floor to be the first one, contrary to European practice. There is no elevator, even though at the time this place was built, they certainly existed. Any self-respecting hotelier with an eye to generating revenue in those days would have had a lift installed.

However, it was a very nice place. We had a large airy room in the front, and the bathroom was equipped with the biggest bathtub I've ever seen in my life. It was a monster, easily three times the size of a "normal" tub; the toilet beside it in the picture is of normal size (a good thing, or you'd fall in trying to use it...but I digress). That will give you some idea of how big the tub is. It was easily two feet deep, and getting in and out is a hazardous undertaking for a geezer. As the image shows, the contours of the bottom clearly indicated it was intended for two people to use simultaneously. No way was that bathtub installed in the 1890's.

However, it was a very nice place. We had a large airy room in the front, and the bathroom was equipped with the biggest bathtub I've ever seen in my life. It was a monster, easily three times the size of a "normal" tub; the toilet beside it in the picture is of normal size (a good thing, or you'd fall in trying to use it...but I digress). That will give you some idea of how big the tub is. It was easily two feet deep, and getting in and out is a hazardous undertaking for a geezer. As the image shows, the contours of the bottom clearly indicated it was intended for two people to use simultaneously. No way was that bathtub installed in the 1890's.

The grassy median between the hotel and the nearby main road was obviously a nesting site for wood pigeons. I've always thought of these as rural birds, but apparently they aren't. They're in the same genus as the the garden-variety street pigeon but are much larger and have distinctive markings, including broad white stripes on their wings that are very noticeable in flight. During the Normandy Invasion Allied airplanes were painted with such stripes to make them easily recognizable to ground anti-aircraft crews. This was done to reduce the chances of a "friendly fire" shoot-down of returning aircraft. Such incidents had plagued the Sicily Invasion and caused significant loss of life.

The grassy median between the hotel and the nearby main road was obviously a nesting site for wood pigeons. I've always thought of these as rural birds, but apparently they aren't. They're in the same genus as the the garden-variety street pigeon but are much larger and have distinctive markings, including broad white stripes on their wings that are very noticeable in flight. During the Normandy Invasion Allied airplanes were painted with such stripes to make them easily recognizable to ground anti-aircraft crews. This was done to reduce the chances of a "friendly fire" shoot-down of returning aircraft. Such incidents had plagued the Sicily Invasion and caused significant loss of life.

Interestingly, I also saw a grey squirrel—Sciuris carolinensis, the kind we have in the USA; a bog-standard Mark I regular-issue grey squirrel—in the same place I saw the wood pigeon. These squirrels are imported exotics in the UK and while we regard them as a game animal, over there they're a major pest, carrying a virus to which they're immune but which is deadly to the native red squirrels. In the rural districts they get shot on sight. Glasgow may be a tough town but for squirrels it's likely safer than the countryside. In Britain, unlike the USA, wild game meat can be sold to the public, and there are specially licensed places to do it. Pheasant, grouse, venison, etc., can be purchased in these places and in some cases, in supermarkets. Ditto grey squirrels, as can be seen from the image above. I've been told it's on the menu in some forward-thinking restaurants in big cities, too!

Given the inclement weather we had for most of the trip we hit several museums. The Kelvingrove Museum was interesting but a bit disorganized, and the Hunterian even more so. But one "museum" of a sort was very interesting. This was the "Tenement House."

Given the inclement weather we had for most of the trip we hit several museums. The Kelvingrove Museum was interesting but a bit disorganized, and the Hunterian even more so. But one "museum" of a sort was very interesting. This was the "Tenement House."

In the US the term "tenement" is more or less equivalent to "slum," but in fact it applies to any apartment building; the Tenement House is in the Garnet Hill district of Glasgow. The National Trust has preserved a middle-class apartment exactly as it was when the former owner lived in it, freezing it in time circa 1935 or so. The entry foyer is lit with a gas fixture, still actually working. (The docent told me the National Trust had to get special permission to do this from the fire authorities!) The kitchen contains a huge cast-iron stove that was used with coal. Imagine having to haul buckets of coal up and of ashes down in order to cook!

In the US the term "tenement" is more or less equivalent to "slum," but in fact it applies to any apartment building; the Tenement House is in the Garnet Hill district of Glasgow. The National Trust has preserved a middle-class apartment exactly as it was when the former owner lived in it, freezing it in time circa 1935 or so. The entry foyer is lit with a gas fixture, still actually working. (The docent told me the National Trust had to get special permission to do this from the fire authorities!) The kitchen contains a huge cast-iron stove that was used with coal. Imagine having to haul buckets of coal up and of ashes down in order to cook!

The docent laid stress on the fact that this was a middle-class apartment, not a home for a poor person. The original owner was a lady who did clerical and office work, who lived there all her adult life. This apartment is typical of the sort of middle-class housing of the day.

Actually, in terms of layout and amenities, the Tenement House apartment isn't too dissimilar to some of the apartments in which the friends of my youth lived, if you leave aside the two fireplaces and that massive stove. One item in the kitchen was a wooden rack for drying clothes that was suspended on pulleys over the kitchen sink; such racks were a normal feature of the apartments along Kingsbridge Avenue, which were roughly contemporary with the Tenement House.

The tenants in this building did their laundry by boiling it in large copper tubs in the back yard, scrubbing it on washboards, and hanging it up to dry. My late mother once told me that when she was a little girl in the 1920's that's exactly how her family did it, too! Considering the Glasgow climate, the drying process would perhaps have been a prolonged one.

We saw other sights in Glasgow, including a cathedral—there's always a cathedral—dedicated to and the shrine for St Mungo, Glasgow's patron and founder, to whom many miracles are attributed, including one of them involving a fire. The Glasgow Fire Brigade named a fireboat after him, a distinction that much surely be unique among the roster of saints.

THE HIGHLANDS

After all these things we set off on the next phase of the adventure. We had come to Glasgow by train, but we went to the airport and rented a car for touring the Highlands. It was a microscopic Hyundai i10, just barely big enough for the two of us and our luggage: at that we had to utilize the rear seat for one suitcase. As I soon learned, the small size of this car wasn't a handicap: it was in fact one of its virtues. Furthermore, by dint of Divine Intervention, when we picked up the car Enterprise offered me an automatic transmission vehicle for the same price as one with a standard shift. I can drive a stick shift, but dealing with the roads was made much easier by not having to be constantly changing gears. If nothing else, it allowed me to grip the steering wheel with both hands, and maintain iron-willed control.

We had come to Glasgow by train, but we went to the airport and rented a car for touring the Highlands. It was a microscopic Hyundai i10, just barely big enough for the two of us and our luggage: at that we had to utilize the rear seat for one suitcase. As I soon learned, the small size of this car wasn't a handicap: it was in fact one of its virtues. Furthermore, by dint of Divine Intervention, when we picked up the car Enterprise offered me an automatic transmission vehicle for the same price as one with a standard shift. I can drive a stick shift, but dealing with the roads was made much easier by not having to be constantly changing gears. If nothing else, it allowed me to grip the steering wheel with both hands, and maintain iron-willed control.

I have many thousands of miles of left-lane driving to my credit, in England, Wales, Ireland, and South Africa. Driving on the left doesn't bother me, and in some ways I prefer it to driving on the right. But the miles I put on that Hyundai are going to be the last ones: it was a terrifying experience every time I got behind the wheel, not because of the car but because of the roads.

There are three classes of roads in the UK, leaving aside the Motorways, which are roughly comparable to our Interstate Highways. "A" and "B" roads are primary routes. Then there are what are lumped together as "Other" roads.

There are three classes of roads in the UK, leaving aside the Motorways, which are roughly comparable to our Interstate Highways. "A" and "B" roads are primary routes. Then there are what are lumped together as "Other" roads.

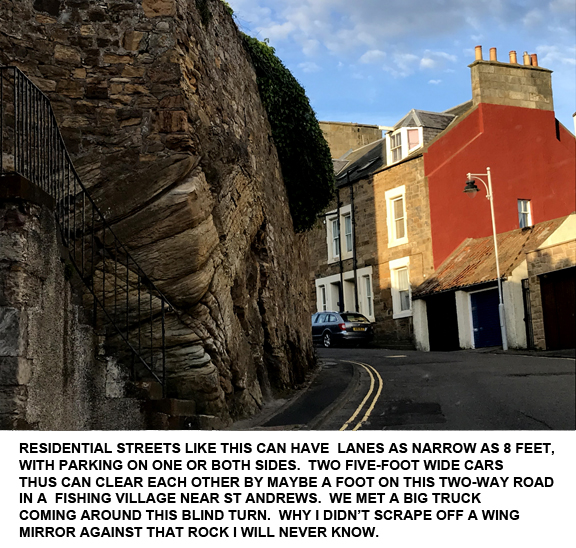

On US main roads travel lanes are 12 feet wide. Furthermore, there are usually fairly generous shoulders so that if you have to pull over or if you need to dodge something, there's a place to go. Not so in Scotland. If there are two lanes on a primary road, each is perhaps at best 9 feet. While a two-way road can be as much as 18 feet wide, many are narrower, especially in residential areas, where the road could be two-way with a total width of less than that nominal 18 feet, and usually with parking on one or both sides. Scottish roads for the most part have no shoulders and no berms. Now, the Hyundai i10 is 5.4 feet wide, not including the wing mirrors. That gave me less than 2 feet of clearance for an obstacle on either side, such as an oncoming vehicle or a wall.

On US main roads travel lanes are 12 feet wide. Furthermore, there are usually fairly generous shoulders so that if you have to pull over or if you need to dodge something, there's a place to go. Not so in Scotland. If there are two lanes on a primary road, each is perhaps at best 9 feet. While a two-way road can be as much as 18 feet wide, many are narrower, especially in residential areas, where the road could be two-way with a total width of less than that nominal 18 feet, and usually with parking on one or both sides. Scottish roads for the most part have no shoulders and no berms. Now, the Hyundai i10 is 5.4 feet wide, not including the wing mirrors. That gave me less than 2 feet of clearance for an obstacle on either side, such as an oncoming vehicle or a wall.

In many places (such as when crossing a small bridge) the road narrows to one 9 foot lane, with bridge abutments (usually made of nice, solid stone) set right up to the very edge.  More often than not such narrowed places are on blind hills, where you will see a cheery sign (probably meant to be reassuring) that reads "Oncoming Vehicles In Middle Of Road." This is less comforting than

More often than not such narrowed places are on blind hills, where you will see a cheery sign (probably meant to be reassuring) that reads "Oncoming Vehicles In Middle Of Road." This is less comforting than  one might think because most of the time you can't see whether there is any oncoming traffic. And if that oncoming traffic is a tour bus or a log truck or a 9-foot-wide tractor-trailer rig it will take up all but six inches of the oncoming lane. Assuming both vehicles crowded the left side of their respective lanes (and believe me, that's exactly what I did) my little Hyundai had all of 2-1/2 feet of "wiggle room." But if that oncoming vehicle drifted towards my side, a not-uncommon occurrence, we stood a very fair chance of being smeared against its side. Or a bridge abutment, take your pick.

one might think because most of the time you can't see whether there is any oncoming traffic. And if that oncoming traffic is a tour bus or a log truck or a 9-foot-wide tractor-trailer rig it will take up all but six inches of the oncoming lane. Assuming both vehicles crowded the left side of their respective lanes (and believe me, that's exactly what I did) my little Hyundai had all of 2-1/2 feet of "wiggle room." But if that oncoming vehicle drifted towards my side, a not-uncommon occurrence, we stood a very fair chance of being smeared against its side. Or a bridge abutment, take your pick.

Things weren't made better by the fact that not only are the roads very narrow, they're also very curvy and you can't see more than 30-40 yards ahead of you. Coming around a blind turn on a blind hill I had to be on my guard every time; even a half-second's inattention meant a real risk of a collision. Some roads are "single track" with what are called "passing places." On such a road there isn't enough room for two cars to pass each other. The "passing place" is a short, somewhat wider section; you're supposed to turn into it and

Things weren't made better by the fact that not only are the roads very narrow, they're also very curvy and you can't see more than 30-40 yards ahead of you. Coming around a blind turn on a blind hill I had to be on my guard every time; even a half-second's inattention meant a real risk of a collision. Some roads are "single track" with what are called "passing places." On such a road there isn't enough room for two cars to pass each other. The "passing place" is a short, somewhat wider section; you're supposed to turn into it and  let an oncoming car go by.

let an oncoming car go by.

On Class A and B roads there are "laybys" and signs that advise motorists to use them "...to allow queues to pass." At left you see the sign advising you of the layby; and also of the presence of speed cameras in the area. Speeding drivers are a continuing problem, it seems; and the UK is very aggressive in using cameras to control it. We saw signs warning us of speed cameras everywhere. Outside the limits of a town or village, even on single track roads, the "National Speed Limit" applies. What, you may ask, is the National Speed Limit? Sixty miles per hour. Even on single track "Other" roads!

To a terrified American such limits seem insanely high, and the thought of driving such roads at 60 MPH is simple lunacy; but the locals are used to it. If a scared Yank daringly gets his nerve up to do 45 MPH, inevitably he'll be overtaken by the impatient guy behind him as soon as there's a clear view of 30 yards of road.

I found the following FAQ on a web site devoted to learning how to drive in the UK:

Q. Why don’t we make roads wider to be safer?

A. As road widths increase, people’s speed increases until the point at which drivers perceive that the road should be two lanes, even though it’s not marked. Narrower roads lead to lower speeds.

This, I think, says it all, and with typical British understatement. I can't imagine what kind of carnage would ensue if they jacked up the limits to, say, 70 MPH on those single track roads.

Mull and Iona

Once we had the car we tore out into the traffic on our way to Oban, jump-off point for the islands of Mull and Iona via a ferry. After some wrong turns on the  Motorway, we finally figured out how to get onto the A82 and northward.

Motorway, we finally figured out how to get onto the A82 and northward.

There isn't much to say about Oban proper, except that our very-conveniently-located B&B was a short walk to the ferry terminal and had private parking, so we could leave the car there. This B&B—which I won't name for fear of a lawsuit for libel, and whose name I have blotted out in the image—was the one exception in terms of quality of the places we stayed.

It's not that it was dirty; it wasn't. The room was adequate and the shower as well; the breakfast was okay. But the place gave me hives. Literally. We spent two nights there; after the first night I woke up with an itchy lump on my neck; the second morning I was all broken out. I have no idea what caused this: perhaps something in the laundry soap the proprietor used, but whatever it was, everything cleared up once we moved on. Never happened anywhere else.

Oban is, as I said, a ferry port for the Islands of Mull and Iona. Mull is quite large as Scottish islands go, but we didn't attempt to take the car there on the ferry (we could have done so). Our ticket, booked in advance, included a bus tour of the island, and a short trip to tiny Iona as well. The bus driver was a real artist: most of the so-called roads were of the single-track variety but he tooled that big double-decker around like a kiddie car. At one point there's a bridge that's even narrower than most, much narrower than the road itself. He eased us over that bridge with perhaps two inches clearance between the bus and the stone wall on either side. He did this in the rain. I take my hat off to him, not only for his skill as a driver, but as a raconteur, keeping up a humorous and informative running commentary the whole time.

Oban is, as I said, a ferry port for the Islands of Mull and Iona. Mull is quite large as Scottish islands go, but we didn't attempt to take the car there on the ferry (we could have done so). Our ticket, booked in advance, included a bus tour of the island, and a short trip to tiny Iona as well. The bus driver was a real artist: most of the so-called roads were of the single-track variety but he tooled that big double-decker around like a kiddie car. At one point there's a bridge that's even narrower than most, much narrower than the road itself. He eased us over that bridge with perhaps two inches clearance between the bus and the stone wall on either side. He did this in the rain. I take my hat off to him, not only for his skill as a driver, but as a raconteur, keeping up a humorous and informative running commentary the whole time.

Mull is a pretty place, and it was there we saw our first Highland cattle. These "hairy coos" are a sturdy breed found in—where else?—the Highlands. They're big, shaggy beasts with formidable horns. We were told they were very gentle and docile, which considering headgear that would have done credit to a Texas Longhorn, was probably a good thing. If a hairy coo ever lost his cool, he could lay a big hurt on someone. These critters wander as they will, anywhere in the villages, constrained only by two cattle guards on the main road.

Iona is alleged to be the place where Christianity first came to Scotland; at one time there was a working cathedral, and a nunnery. Iona must have been a pretty bleak place in the winter in Medieval times (well, now, too, I suppose) as it's open to the North Atlantic. Gulf Stream or no Gulf Stream, anyone living in a stone building with no heat would have found winter a real test of faith. In the yards around the nunnery buildings (what is left of them after more than a thousand years) there are what look like graves. If there was a convent school, this is probably where they buried students who died after being flogged with rosary beads for not properly memorizing their Catechism lessons.

Iona is alleged to be the place where Christianity first came to Scotland; at one time there was a working cathedral, and a nunnery. Iona must have been a pretty bleak place in the winter in Medieval times (well, now, too, I suppose) as it's open to the North Atlantic. Gulf Stream or no Gulf Stream, anyone living in a stone building with no heat would have found winter a real test of faith. In the yards around the nunnery buildings (what is left of them after more than a thousand years) there are what look like graves. If there was a convent school, this is probably where they buried students who died after being flogged with rosary beads for not properly memorizing their Catechism lessons.

The Train

My wife and I subscribe to "Acorn TV," a streaming service that programs British shows, mainly. Two shows we watched in particular can be viewed as generating this trip. One of these was "Hamish MacBeth," a series loosely (very loosely) based on the mystery novels by M.C. Beaton. Another was a travelogue hosted by an actress named Julie Walters, entitled "Coastal Railways." More on "Hamish MacBeth" will be forthcoming, but first, "Coastal Railways."

My wife and I subscribe to "Acorn TV," a streaming service that programs British shows, mainly. Two shows we watched in particular can be viewed as generating this trip. One of these was "Hamish MacBeth," a series loosely (very loosely) based on the mystery novels by M.C. Beaton. Another was a travelogue hosted by an actress named Julie Walters, entitled "Coastal Railways." More on "Hamish MacBeth" will be forthcoming, but first, "Coastal Railways."

Scotland has three major industries: whiskey, tourism, and Harry Potter. You encounter Harry Potter themed stuff everywhere you go: Harry Potter books, Harry Potter mugs, Harry Potter games, Harry Potter bobbleheads, Harry Potter clothing, Harry Potter underwear, and for all I know, Harry Potter toilet paper. The Elephant House pub in Edinburgh advertises itself as "The Birthplace of Harry Potter," because part of the manuscript for the first book in the series was written there.

Scotland has three major industries: whiskey, tourism, and Harry Potter. You encounter Harry Potter themed stuff everywhere you go: Harry Potter books, Harry Potter mugs, Harry Potter games, Harry Potter bobbleheads, Harry Potter clothing, Harry Potter underwear, and for all I know, Harry Potter toilet paper. The Elephant House pub in Edinburgh advertises itself as "The Birthplace of Harry Potter," because part of the manuscript for the first book in the series was written there.

The author of the Harry Potter books is reputed to be the richest woman in the world, richer even than the Queen of England (And if I were that rich, I'd buy Britannia and put her back in service as my plaything...but I digress).

It seems Ms. Julie Walters had a major role in the Harry Potter movies (I've seen one of them and frankly, found it such a snoozer I can't imagine what the fuss is all about). In the first episode of the TV show she took her viewers for a ride on the "Jacobite Steam Train." I assume she was tapped for this because of her part in the movies.

It seems Ms. Julie Walters had a major role in the Harry Potter movies (I've seen one of them and frankly, found it such a snoozer I can't imagine what the fuss is all about). In the first episode of the TV show she took her viewers for a ride on the "Jacobite Steam Train." I assume she was tapped for this because of her part in the movies.

The Jacobite is an old puffer that was restored and used in the Harry Potter films as the "Hogwarts Express," carrying Harry and his talented comrades to Hogwarts, the training school for wizards. In the course of its run the Jacobite traverses a very, very picturesque viaduct. You can ride on this very same train, if a) you're a Harry Potter nut; b) you are willing to spend an inordinate amount of money to sit in an open-windowed coach behind a snorting engine that sprays  fumes and cinders in your eyes; and c) you book the trip at least a year in advance. No kidding: the thing is that popular. It isn't mandatory that one wear a wizard's hat and wave a wand while riding but many of the passengers do.

fumes and cinders in your eyes; and c) you book the trip at least a year in advance. No kidding: the thing is that popular. It isn't mandatory that one wear a wizard's hat and wave a wand while riding but many of the passengers do.

We made a nightmarish drive from Oban to Fort William, from whence the train leaves for the seaside village of Mallaig 80-odd miles away. We couldn't get on to the Jacobite, but that was no hardship. Anyone wanting to see the same sights and ride on the same track, can just walk up and buy a ticket on the regular train at the station in Fort William for half the price of the Jacobite cum Hogwarts Express. This we did. And yes, we saw the Glenfinnan Viaduct, just as Harry does in the films. The only reason for Mallaig's existence seems to be to act as the terminus for the Jacobite and a ferry port for people who want to do it the old-fashioned way, going "Over The Sea To Skye," as the famous song about Bonnie Prince Charlie has it. Because there is absolutely nothing to do in Mallaig, we took the next train right back to Fort William.

Plockton

I'm getting ahead of myself here, but since I mentioned the the Hamish MacBeth TV show I might just as well get it in now. It was filmed in the beautiful little village of Plockton, which played the role of the fictional "Lochdubh." Plockton is reachable only by one of those "Other" single-track roads. But after negotiating the blind curves and miscellaneous other hazards associated with the road, you are rewarded by one of the prettiest places in the Highlands.

I'm getting ahead of myself here, but since I mentioned the the Hamish MacBeth TV show I might just as well get it in now. It was filmed in the beautiful little village of Plockton, which played the role of the fictional "Lochdubh." Plockton is reachable only by one of those "Other" single-track roads. But after negotiating the blind curves and miscellaneous other hazards associated with the road, you are rewarded by one of the prettiest places in the Highlands.

After its brief period of fame when the show was being aired in the early 1990's, Plockton went back to its former obscurity. Nevertheless some places are recognizable to those who watched the show, and at least one has a sign out front announcing that it was used in the series. Nowadays Plockton is a sleepy one-street fishing village chiefly notable for its beauty and excellent seafood. We saw a lot of pretty villages in Scotland, but this one was my favorite.

Isle of Skye

Plockton was a brief diversion as we doggedly made our way to the famous Isle of Skye and its "capital," the town of Portree.

The B&B in Portree can only be described by the quaint adjective "twee." The place was immaculate, and our room was done up in purple satin. Garden gnomes and other small statuary were abundant. Every piece of china at the breakfast table, decorated with a profuse floral pattern, matched; as did the tablecloth and the place mats that protected the tablecloth. Everything was just so.

The Isle of Skye is a very beautiful place, chock-a-block with scenery. But its roads are even more of a nightmare than those in the rest of Scotland. Luckily our hostess at the B&B had a flyer from a local company who take small groups on eight-hour tours around the Isle; we very wisely opted to let their driver deal with the roads and incredible amount of tourist traffic they carry and for which they're utterly inadequate. At every stopping place there were hordes of people, and God alone knows how many vehicles from all over Europe. Yes, Skye is very beautiful, but had I been driving, I'd not have seen any of it at all. The driver would stop periodically and let us out to oooh and aaah. He was a very amiable guy, very funny, and inclined to flirt with two pretty girls in the group.

Skye—as is true everywhere in the Highlands—has gazillions of sheep. There are more sheep than people in the Highlands, in fact. Everywhere we went we saw sheep, mostly Cheviots, which our guide referred to as "...evil clone sheep," perhaps because Dolly was a Cheviot. There were some black-faced Highland sheep too, but the Cheviot was the most common breed. There were also signs that showed that sheep farmers were very protective. Lots of them, warning against allowing dogs to roam free, because if they did they'd be shot for "worrying" sheep. This is apparently perfectly legal.

Skye—as is true everywhere in the Highlands—has gazillions of sheep. There are more sheep than people in the Highlands, in fact. Everywhere we went we saw sheep, mostly Cheviots, which our guide referred to as "...evil clone sheep," perhaps because Dolly was a Cheviot. There were some black-faced Highland sheep too, but the Cheviot was the most common breed. There were also signs that showed that sheep farmers were very protective. Lots of them, warning against allowing dogs to roam free, because if they did they'd be shot for "worrying" sheep. This is apparently perfectly legal.

Culloden Moor and Tain

We were on our way to the town of Tain, as far north as we were going to go, and pretty far north it was, too. We made another diversion to the battlefield of Culloden Moor, where the Jacobite forces of Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Stuart Pretender to the throne, were soundly routed by the army of the Hanoverian King George II, led by the Duke of Cumberland. This was a decisive battle in Scottish history, putting an end once and for all to the hope of restoring the Catholic Stuarts to the throne. There's a nice interpretive center there and a filmed four-screen re-enactment of the battle that is probably as confusing as the real thing was. The defeated Prince fled to the Isle of Skye (that's what the song is about) and never returned for a second try. Culloden is to Scotland what Gettysburg is to the US: the final failed effort to save a doomed Cause.

We were on our way to the town of Tain, as far north as we were going to go, and pretty far north it was, too. We made another diversion to the battlefield of Culloden Moor, where the Jacobite forces of Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Stuart Pretender to the throne, were soundly routed by the army of the Hanoverian King George II, led by the Duke of Cumberland. This was a decisive battle in Scottish history, putting an end once and for all to the hope of restoring the Catholic Stuarts to the throne. There's a nice interpretive center there and a filmed four-screen re-enactment of the battle that is probably as confusing as the real thing was. The defeated Prince fled to the Isle of Skye (that's what the song is about) and never returned for a second try. Culloden is to Scotland what Gettysburg is to the US: the final failed effort to save a doomed Cause.

We stopped there on our way to Tain, where I was to meet with Kim S., another person with whom I have communicated for years but never met face to face until this trip. Kim is now retired but was a guide on a shooting and fishing estate for many years. We stayed at a nice place he recommended and on our first evening we had dinner with him and his lovely wife Liz at a local pub; a very good one, too. The following day Kim took me in to Tain to visit R. Macleod & Son, the best gun shop in Scotland, from what I was told and saw.

Americans think that the British can't own guns, but this is not really true. Though their restrictions and rules are outrageous by American standards and would never be tolerated here, it's nevertheless possible to buy a gun if you go through the hoops. True, you can't own handguns any more, and rifles need special paperwork, but it's relatively simple to buy a shotgun. And boy, did Macleod have shotguns. Hundreds of them on display of all types suitable for sporting use. Mostly high-end doubles, primarily over/unders, but some other types. Macleod also sells all types of gear for outdoors use, pricey optical goods, and a wide variety of general hardware. Rifles, too. Everything was attached to the wall racks and could only be accessed by the dealer; and all the rifles with removable bolts had them removed and presumably stored under lock and key. Again, this level of security would be highly unusual in the USA, but safe-storage rules in Scotland are very stringent.

Americans think that the British can't own guns, but this is not really true. Though their restrictions and rules are outrageous by American standards and would never be tolerated here, it's nevertheless possible to buy a gun if you go through the hoops. True, you can't own handguns any more, and rifles need special paperwork, but it's relatively simple to buy a shotgun. And boy, did Macleod have shotguns. Hundreds of them on display of all types suitable for sporting use. Mostly high-end doubles, primarily over/unders, but some other types. Macleod also sells all types of gear for outdoors use, pricey optical goods, and a wide variety of general hardware. Rifles, too. Everything was attached to the wall racks and could only be accessed by the dealer; and all the rifles with removable bolts had them removed and presumably stored under lock and key. Again, this level of security would be highly unusual in the USA, but safe-storage rules in Scotland are very stringent.

My wife had been telling me I needed a haircut, so I asked Kim if he knew a local barber shop I could go to. He certainly did. He took me to a gentleman who was definitely a barber of the Old School: Mr Frank Martin. Mr Martin runs a one-chair shop in Tain; and he's been doing it a long, long time. He is 92 years old, and told me he'd been cutting hair for 74 years! He did a nice job too: my wife approved of the result.

My wife had been telling me I needed a haircut, so I asked Kim if he knew a local barber shop I could go to. He certainly did. He took me to a gentleman who was definitely a barber of the Old School: Mr Frank Martin. Mr Martin runs a one-chair shop in Tain; and he's been doing it a long, long time. He is 92 years old, and told me he'd been cutting hair for 74 years! He did a nice job too: my wife approved of the result.

I've long since resigned myself to the disappearance of real barber shops in the US and their replacement by "salons" run by "hairdressers" instead of barbers. At one time a barber shop was a sort of men's club: a more or less completely masculine environment with certain rituals and customs that were universally observed. Nowadays such shops are pretty much gone in most places in this country. It was good to see that someone is keeping the old ways alive.

The next day we had coffee with Kim and Liz, at their home. Kim was kind enough to show me his guns: a beautiful Browning over/under 12 gauge shotgun and a Mauser Model 66 sporting rifle in .270 Winchester. Although we'd only met in person a day before, they made my wife and me feel truly at home. I wish we'd had more time to visit before we had to leave.

On to Inverness and St Andrews

We were headed eventually for St Andrews, a historic university city. Along the way we made a brief stop in Inverness, making a side trip to Cawdor Castle. Anyone who has read any Shakespeare knows that MacBeth yearned to be "Thane of Cawdor," but we were told that "Shakespeare was wrong, that play was written before there was Cawdor Castle." Then in the next breath we were told the Castle dates to the 14th Century. Shakespeare wrote "The Scottish Play" in the 17th century! You pays your money and takes your choice in this one.

Along the way to St Andrews we went on through a place called Aviemore, specifically to attend a demonstration of sheepdogs at work. Sheep are everywhere in the Highlands: a field or pasture without them is an unusual sight. Anyone who has sheep has sheepdogs; it's nearly impossible to control a flock any other way. The dog is as important as the shepherd, really.

Along the way to St Andrews we went on through a place called Aviemore, specifically to attend a demonstration of sheepdogs at work. Sheep are everywhere in the Highlands: a field or pasture without them is an unusual sight. Anyone who has sheep has sheepdogs; it's nearly impossible to control a flock any other way. The dog is as important as the shepherd, really.

"Sheepdog" is synonymous with "Border Collie"; we never saw any other breed. Since we have had two Border Collies since 1996 (both with ancestors in Scotland) any time we get a chance to see these marvelous dogs at work, we will go. We had a devil of a time finding the farm where the demonstration was held, but we got there with ten minutes to spare.

There were eight dogs working the flock of sheep under the direction of the shepherd, who controlled them over amazing distances using whistled commands. The dogs knew when to run, which way to run, and when to stop and "hold" the sheep simply "by eye."

Border Collies have a characteristic "crouch" and a stare that seems to mesmerize the sheep and make them stand still. Even though sheep are about as dumb a quadruped can get and still be able to walk, they do understand certain things. Part of the success of the sheep/dog equation is not only the way the dogs behave, but the way sheep themselves behave. Dogs are carnivores, sheep are herbivores; and carnivores eat herbivores. The sheep know this. They know that dog = wolf, and that wolves are to be avoided at all costs. Since they're herd animals when they perceive danger they instinctively huddle up into a compact mass; the more sheep in the flock the bigger and tighter the huddle is.

While cattle form a defensive perimeter allowing them to use their horns if needed, each sheep in the huddle is just hoping the dog will choose to kill some other sheep, not him. Therefore the sheep do whatever the dog tells them to do, hoping to placate the dog. The dog always wins and thus whoever controls the dog(s) controls the flock. Once in Ireland we watched two dogs control more than a hundred sheep at a time, making them go where the shepherd wanted them to go (eventually to a slaughterhouse, but the sheep didn't know that).

We watched those dogs run the sheep over a field hundreds of yards in length and breadth, turning them and stopping them on command from the shepherd. Then one specific sheep was cut out of the mob by the dogs—at the shepherd's command, and I have no idea how you train a dog to know which one you want—so the shepherd could do a shearing demonstration. He  grabbed the sheep by its horns and plopped it up on its rump as if it were sitting in a chair. A sheep in this position looks pretty silly, but it won't try to get loose and the shepherd can completely control the sheep while he works the shears. The pack of dogs watched closely (perhaps hoping against hope to get the "KILL" command, which never came).

grabbed the sheep by its horns and plopped it up on its rump as if it were sitting in a chair. A sheep in this position looks pretty silly, but it won't try to get loose and the shepherd can completely control the sheep while he works the shears. The pack of dogs watched closely (perhaps hoping against hope to get the "KILL" command, which never came).

At one moment I was subjected to sore temptation. There was a litter of puppies on display, and one of them was plopped into my hands. Now, I am a sucker for dogs in general, Border Collies in particular, and Border Collie puppies even more so. This little rascal was as cute as he could be, lethally cute, really dangerously cute. He may have been as much as five weeks old, still small enough that I could have slipped him into the pocket of my raincoat. It was very, very cold, actually freezing cold. This was mid-June and the temperature was low enough that there was sleet falling. Surely it would have been a humane thing to do to put him into a nice warm pocket, out of the wind, wouldn't it? The danger was that if I had done so I'd have to bring him home, and that would have greatly complicated things.

Coming out of Inverness after a second night we stopped briefly at Fort George, an Army post, then across the heart of the Highlands on the highly scenic A9. At least I was told it was highly scenic, since we went through the Cairngorms National Park. How scenic it was I don't know from personal observation because I was driving and didn't dare look.

We didn't actually stay in St Andrews proper: nothing was available, so we'd booked a place in Crail, a few miles

We didn't actually stay in St Andrews proper: nothing was available, so we'd booked a place in Crail, a few miles  south of there. This was a really beautiful and well-appointed place, much the nicest B&B we stayed in, but finding it presented some difficulty. It was located behind The Back Of Beyond, literally in the middle of farm fields. Oh, yes, we had a GPS but it seems that in the UK, these things work somewhat differently than in the USA. American GPS units rely on street addresses. I'd downloaded maps of Scotland from Garmin, and that allowed us to find any place in a city with an actual address. But...this beautiful B&B didn't have one.

south of there. This was a really beautiful and well-appointed place, much the nicest B&B we stayed in, but finding it presented some difficulty. It was located behind The Back Of Beyond, literally in the middle of farm fields. Oh, yes, we had a GPS but it seems that in the UK, these things work somewhat differently than in the USA. American GPS units rely on street addresses. I'd downloaded maps of Scotland from Garmin, and that allowed us to find any place in a city with an actual address. But...this beautiful B&B didn't have one.

A "sat-nav" in the UK can be told to find a specific postal code. If the postal code is, say, "PA27 8BU" you plug that in and the sat-nav will find it. Our Garmin unit had no such capacity. We had to call the B&B several times while cruising a B class road to ask directions. Once we found it we were pleased, the more so because it wasn't on a road at all, not even an "Other road." It was at the end of a farm track more suitable for tractors than automobiles: there was grass growing in it!

Once we'd settled in, we went into Crail for dinner. And then...we couldn't find the place again! The proprietress has sent us into Crail by a back road even worse than the one we'd come in on, and we spent a good hour and a half trying to find that road again. In the end we went back into Crail several times, and finally we decided to do it the way we'd first come in. That worked: only two hours after leaving the restaurant (the first time) we made it back to the B&B again.

Once we'd settled in, we went into Crail for dinner. And then...we couldn't find the place again! The proprietress has sent us into Crail by a back road even worse than the one we'd come in on, and we spent a good hour and a half trying to find that road again. In the end we went back into Crail several times, and finally we decided to do it the way we'd first come in. That worked: only two hours after leaving the restaurant (the first time) we made it back to the B&B again.

As nice as this place was, there was one thing that gave us pause: it had no shower, only a bathtub. A very nice, very deep bathtub, in a very elegantly appointed bathroom. But the tub was so deep that we thought that maybe after getting down into it we'd not be able to get out again without calling 9-9-9 to get the emergency squad in. There was one of those telephone-handset things with a sprayer on it, but a sign warned us that this was only for washing hair, and not to be used as a shower.

St Andrews, our last stop before we returned the car in Edinburgh, was a bit of a disappointment. We walked around: it was a pretty place but for a university town on a Friday night, it seemed to be more or less dead. At one point we were trying to find somewhere with free wi-fi and were simply unable to find anything open. There was—I am not making this up—a Starbucks that was closed at 5:00 PM! Don't British students drink coffee? Whoever heard of a Starbucks in a university town, of all places, being closed at 5:00 PM?

The drive back to Edinburgh Airport (where we returned the car) led us through several beautiful fishing villages along the coast, and eventually into the maelstrom of the M90 Motorway.

The drive back to Edinburgh Airport (where we returned the car) led us through several beautiful fishing villages along the coast, and eventually into the maelstrom of the M90 Motorway.

Despite having two weeks' experience driving in Scotland at that point, I was foolish enough to miscalculate how long it would take us to get to the airport. The map said the trip from Crail was 35 miles: it took us two hours on the ghastliest roads we'd yet encountered, driving through any number of small towns along the coast, to cover that distance.

Once at the airport I turned in the car: 906 miles in all, with nary so much as a scratched fender. I have to say that despite the hair-raising roads and the colossal amount of traffic we encountered everywhere we went (far, far more than we'd anticipated), I deserved a pat on the back for getting away unscathed. But never again. The next trip will have to involve a ship that we'll be aboard for at least a week, so that we only have to unpack once.

The weather we encountered was simply awful. Sleet at the sheepdog demonstration was perhaps the low point, but in the three weeks we were gone we had two and a half days when it wasn't raining. All the local residents insisted this was abnormal for mid-June and that ordinarily the weather was "very pleasant" that time of year. Ha!

I liked Edinburgh and Glasgow, but to my mind the small villages and towns we visited were the most attractive localities. While Plockton was my favorite, there were others nearly as attractive. This is Glencoe:

But second only to Plockton, I would say that Inverary was my favorite place. I liked the effect of clean white buildings set against the backdrop of the sky; and the green grass and foliage were a perfect accent. Inverary also stands out in my memory because of a small park-like setting across from the Inverary Inn. It's dedicated to something ubiquitous in small Scottish towns: a war memorial.

The Scots are a fighting race and they honor in perpetuity those who fell in defense of Scotland, King, and Country. While the huge National War Memorial is dedicated to all Scots who died in the country's wars, these smaller monuments honor the dead from a specific locality. Such monuments typically include a statue of a soldier in full kit and a list of the names of those from the community who died in service. Most were erected shortly after The Great War of 1914-18; later there were added to them additional plaques for the fallen in the Second World War and other conflicts.

The British Army is based on a regimental system, in which men are recruited from specific localities. Inverary's men served together, and all too many of them died together in the wholesale slaughterhouses of the Somme, Paschendale, Ypres, and many other places whose names still conjure up a sense of dread. Britain lost a million young men in The Great War, most of them from small places like Inverary. They would have known each other from boyhood, would have grown up together, gone to the same schools, and come from families whose lives were intertwined in many ways.

The population of beautiful Inverary is a little over 600 today; in 1914 it was even smaller. There are 83 names on the memorial, 74 of them just from The Great War. How does such a small place absorb the loss of an entire generation of young men? The sense of loss and enduring grief—still felt after two generations and more than a century—is repeated over and over. The monuments are mute testimony to the staggering impact of The Great War, and how its effects are felt to this day, not only in Scotland, but in the UK and the rest of the world.

Every town and village we visited had a memorial like this. Every one.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |