MR. HYDE’S GIFT

This story was orginally submitted to Field & Stream magazine. They rejected it.

In 1961 I was a 13-year-old city kid who had long dreamed of living in the country, but whose chances of doing so seemed to be slim to none. After more than decade on this planet, I had laid eyes on exactly one cow—in the Bronx Zoo, believe it or not—and my exposure to “wildlife” was limited to sparrows, street pigeons, and the occasional squirrel. Apart from the highly illicit slingshot I’d fabricated from a tree branch and a few rubber bands, I owned nothing that could legitimately be considered a weapon. In a desperate attempt to get some outdoors experience I’d

In 1961 I was a 13-year-old city kid who had long dreamed of living in the country, but whose chances of doing so seemed to be slim to none. After more than decade on this planet, I had laid eyes on exactly one cow—in the Bronx Zoo, believe it or not—and my exposure to “wildlife” was limited to sparrows, street pigeons, and the occasional squirrel. Apart from the highly illicit slingshot I’d fabricated from a tree branch and a few rubber bands, I owned nothing that could legitimately be considered a weapon. In a desperate attempt to get some outdoors experience I’d  joined the Boy Scouts, but my troop rarely went on camp-outs; when they did it was to Staten Island.

joined the Boy Scouts, but my troop rarely went on camp-outs; when they did it was to Staten Island.

But in that year my life took a promising turn: my physician father bought a country house in Dutchess County, New York. The place had everything I had yearned for, including a sizeable patch of woods and a stream and pond. I discovered to my delight that hidden behind a door the previous owner had left behind a Montgomery Ward’s single-shot 20 gauge. I promised myself that just as soon as I turned 14, the minimum age for a small game license, I was going to do some hunting with it. In the interim, however, I decided to learn how to fish. I knew even less of fishing than I did of hunting, but in the welter of stuff that came with the house I’d found an ancient rod and reel that had to have dated from well before 1920.

It was a short, stiff, hollow metal casting rod, perhaps five feet long, with a horizontal baitcasting reel so primitive it lacked the level-wind mechanism that’s been used on every reel manufactured since the Great Depression. The reel was wound with black cotton fishing line—not nylon, cotton—that must have come in a shipment out of the Sears Wish Book, a shipment that undoubtedly contained a couple of coal-oil lamps and likely some high-button shoes. The line was stout enough to anchor duck decoys; it would have been more than adequate for the ten-inch trout in my father’s pond, in case I ever figured out how to catch them. After a few fruitless and frustrating sessions with that prehistoric tackle I knew I needed some instruction in state of the art fishing, but finding that instruction wasn’t easy. However, I’ve always been a bookworm. I knew that somewhere, someone had written down everything there was to know about fishing, so I went about the business of finding the appropriate sources of information.

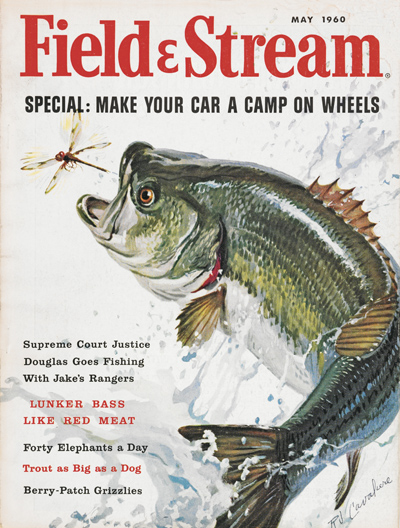

Up to that point I’d not done much more than glance at the cover of Field & Stream, which was sold in Leitner’s candy store on the corner of my street. Why they bothered to carry it I’ll never know, because it couldn’t have been a big seller in my working-class Bronx neighborhood; but Mr Leitner always had the latest issue. Field & Stream was a “twofer” as far as I was concerned, since I had to teach myself how to hunt. Each month’s issue became my textbook on these subjects.

Up to that point I’d not done much more than glance at the cover of Field & Stream, which was sold in Leitner’s candy store on the corner of my street. Why they bothered to carry it I’ll never know, because it couldn’t have been a big seller in my working-class Bronx neighborhood; but Mr Leitner always had the latest issue. Field & Stream was a “twofer” as far as I was concerned, since I had to teach myself how to hunt. Each month’s issue became my textbook on these subjects.

The ads were terrifically informative, although the articles were pretty arcane to someone whose outdoors experience was significantly less than zero. The hunting articles were all about man-eating grizzlies, monster whitetails, and moose in Alaska. I was aware that whitetails supposedly existed in Dutchess County but I’d never seen one in the flesh nor knew anyone who had. That didn’t matter: I couldn’t get a big game license until I was 16 anyway. So fishing became my initial topic of study.

I found out there was some wonderful stuff called “monofilament” line and it was used on “spinning” reels. These latter were allegedly so simple anyone could catch fish with them. I had no such equipment, and for reasons that escape me now, forty-five years later, it never occurred to me to ask my father to buy any of it for me. It might not have mattered: although Leitner’s sold Field & Stream, they absolutely didn’t sell fishing tackle, and I wouldn’t have had the slightest idea where to get it anyway.

For a year or so I struggled to learn how to fish, but was so lousy at it I gave it up. The gear I had was simply too crude for a raw beginner. Totally frustrated, I tossed my antique rod and reel in the corner and directed my attention to the hunting stories. In the Spring of 1962 I managed to nag my father into buying me a .22 rifle, and calm his fears about my using that little shotgun come November. I took the mandatory Hunter Safety course, got my first license (I still have it) and became a reasonably successful autodidact in small game hunting. I became good enough at it, in fact, that I began to develop something akin to resentment whenever F&S devoted most of an issue to fishing. Fishing was a waste of time. Hunting was what mattered. The magazine should have split into Field and Stream and not devote half their coverage to an insignificant and unimportant subject.

Sometime—I guess it must have been during the Summer of 1964— I was walking along the gravel road in front of the house. An elderly man had stopped his car in front of our driveway and was looking at the property. I asked if I could help him and he replied, “I just want to look around; this used to be my old stomping grounds.” (I had never before, nor have I since, heard anyone else use that expression.) His name, he said, was Mr. Hyde. I suppose  he must have told me his first name, but I don’t remember what it was. I invited Mr. Hyde in and introduced him to my father. That’s almost the last I remember of the encounter; he spent some time with my father in polite chit-chat about the house and who’d lived there, and the sort of thing that “grownups” talk about, not of much interest to me. But as he turned to leave, Mr Hyde asked me to come with him to his car. “I’ve got something for you,” he said.

he must have told me his first name, but I don’t remember what it was. I invited Mr. Hyde in and introduced him to my father. That’s almost the last I remember of the encounter; he spent some time with my father in polite chit-chat about the house and who’d lived there, and the sort of thing that “grownups” talk about, not of much interest to me. But as he turned to leave, Mr Hyde asked me to come with him to his car. “I’ve got something for you,” he said.

From the trunk he produced a fishing reel. It was not new, but it was in good shape. And by golly, it was a genuine spinning reel, a South Bend “Spincast 66,” the sort of reel you used with monofilament line. It was even made by a company I’d heard of, and whose ads I’d seen in F&S. He handed it to me, wished me luck in using it, and that was the last I ever saw of Mr. Hyde. He is certainly dead now but that brief encounter and his act of kindness has had a lasting impact on my life.

Naturally, with this fancy new reel in my hands, I had to give fishing another try. I immediately tossed the old one out (in retrospect, a foolish move: that clunker would be worth a year of someone’s college tuition today) and put the Spincast 66 in its place. The spool was full, and a good thing, too: I had no idea where to buy monofilament line.

I now had what was—at least theoretically—a functional rod and reel combination. I tried a few casts with it, and sure enough, the ads were right: anyone could do it. The advantages of this state-of-the-art technology were immediately obvious. I caught the trick of casting pretty quickly, and though I wasn’t much good at hitting my mark or getting the line to go very far, it was orders of magnitude better than I had been able to do with that old thumb-buster reel. I was delighted. The next step was to figure out what fish ate and use the knowledge to catch some. F&S went into excruciating details about “lures,” and how to use them. Lures, that’s what I had to have.

There was a general store in town two miles away, where one might reasonably expect to find fishing lures. I walked into town and sure enough, on the wall of the store was a display of lures. One of them was a lure I had seen advertised in F&S. It was called the “VIVIF,” a name that I knew from my French class meant “living.” Very appropriate: the front end of this rubber lure was shaped like a very realistic minnow’s head; the rear had a sort of dihedral tail that hung over two serious-looking hooks. The tail waggled back and forth as the lure was dragged through the water. The package promised that no fish could resist a VIVIF; it was guaranteed to work, a strike on every cast. I bit as hard as the fish were supposed to, bought it, and walked home again.

And to my delight I found that the makers of that lure weren’t lying, at least not by much. For as long as that lure lasted, I did get a strike on every cast—near enough, anyway. I had yet to delve into the mysteries of setting a hook, a hook damned near as big as the trout I was trying to catch; but that VIVIF did in fact provoke a hit from a fish the first few times I dragged it across their noses.

This was very encouraging. I wasn’t even discouraged when I found out that after a few strikes, the fish wised up to the fact that it wasn’t a real minnow, and thereafter ignored it. But the next weekend when we went to the country I’d come back, break out the tackle, and they’d fall for the VIVIF all over again. Eventually I even caught some of the dumber inhabitants of that pond. The VIVIF was simply spectacular, a heartening proof to an adolescent that grownups did not, in fact, always lie.

Inevitably, though, the VIVIF died. The rubber tail fell off, a victim of sunlight, ozone, and waggling it through the water too many times. Tail-less, the VIVIF was worthless. It didn’t even make a good sinker. I searched for a new VIVIF, but in vain. The general store had sold them all and no one seemed to know where to get another. I switched to other artificial lures, with no luck. It’s a funny thing: since losing that VIVIF I’ve never caught another fish on any artificial lure. I solved the problem by giving up on artificial lures altogether, as soon as I discovered that brook trout would readily take worms, and I’ve never looked back. I’m now a Disciple of The Doctrine Of Live Bait.

But this story really is about that Spincast 66. It can’t be said to have started me in fishing—that credit has to go to the antique baitcasting tackle—but certainly, the Spincast 66 was the single most important piece of equipment that kept me fishing, however desultorily and intermittently, for years. Had it not been for that reel I’d have quit and never tried again, I’m convinced. It taught me that spinning reels, especially closed-face ones, are the way to go. I’ve since learned to use an open-faced spinning reel, but still prefer the closed type. What copywriters for outdoor catalogs like to call “Serious Fishermen ” might regard closed-faced reels as suitable only for kids using Mickey Mouse Fishing Outfits, but they work better than anything else in my hands.

But this story really is about that Spincast 66. It can’t be said to have started me in fishing—that credit has to go to the antique baitcasting tackle—but certainly, the Spincast 66 was the single most important piece of equipment that kept me fishing, however desultorily and intermittently, for years. Had it not been for that reel I’d have quit and never tried again, I’m convinced. It taught me that spinning reels, especially closed-face ones, are the way to go. I’ve since learned to use an open-faced spinning reel, but still prefer the closed type. What copywriters for outdoor catalogs like to call “Serious Fishermen ” might regard closed-faced reels as suitable only for kids using Mickey Mouse Fishing Outfits, but they work better than anything else in my hands.

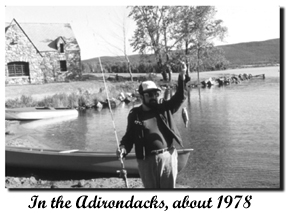

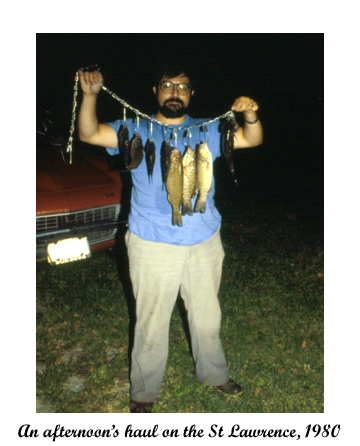

Over the subsequent years of course I bought a good deal of fishing tackle, but that old Spincast always seemed to come along on nearly every fishing expedition, whether on the New River, or anywhere else I might be going. I continued to use Mr. Hyde’s gift for every fishing season from 1964 on, with breaks for military service and a few other episodes in my life. It went off to college with me to catch sunfish in streams in Knox County, Ohio. It caught fish out of the St. Lawrence River in the 1980’s, on a memorable vacation in the Thousand Islands. It dragged up a few sleepy catfish out of game commission lakes in Virginia; it went to Canada and caught my first walleye out of the Ottawa River. With it I took a very respectable largemouth bass in a Texas lake that was more noted for cottonmouth snakes than fish. It hauled in a state-citation-size yellow perch out of Claytor Lake. It’s been used on the New River for 16 seasons to catch smallmouth bass, rock bass, and bluegills beyond counting. It’s caught a lot of fish, and it works as well as ever it did in Mr. Hyde’s hands. Along the way it’s acquired some honest wear and scars but it’s still tight and runs smoothly. None of the reels I’ve bought along the way has been better, and quite a few have been worse.

Over the subsequent years of course I bought a good deal of fishing tackle, but that old Spincast always seemed to come along on nearly every fishing expedition, whether on the New River, or anywhere else I might be going. I continued to use Mr. Hyde’s gift for every fishing season from 1964 on, with breaks for military service and a few other episodes in my life. It went off to college with me to catch sunfish in streams in Knox County, Ohio. It caught fish out of the St. Lawrence River in the 1980’s, on a memorable vacation in the Thousand Islands. It dragged up a few sleepy catfish out of game commission lakes in Virginia; it went to Canada and caught my first walleye out of the Ottawa River. With it I took a very respectable largemouth bass in a Texas lake that was more noted for cottonmouth snakes than fish. It hauled in a state-citation-size yellow perch out of Claytor Lake. It’s been used on the New River for 16 seasons to catch smallmouth bass, rock bass, and bluegills beyond counting. It’s caught a lot of fish, and it works as well as ever it did in Mr. Hyde’s hands. Along the way it’s acquired some honest wear and scars but it’s still tight and runs smoothly. None of the reels I’ve bought along the way has been better, and quite a few have been worse.

I have learned through bitter experience that level wind reels are not for me. A few years ago I succumbed to the siren song of temptation and bought a beautiful one, a sleek Scandinavian product as shapely and glistening as a Swedish movie actress. It was so gorgeous I couldn’t resist, even though it cost enough to have paid for all the rest of my tackle twice over.

I have learned through bitter experience that level wind reels are not for me. A few years ago I succumbed to the siren song of temptation and bought a beautiful one, a sleek Scandinavian product as shapely and glistening as a Swedish movie actress. It was so gorgeous I couldn’t resist, even though it cost enough to have paid for all the rest of my tackle twice over.

That reel was a total bust. Every single cast, no matter how I adjusted it, resulted in a bird’s-nest-size snarl that required scissors to clear. I went through at least 1000 yards of monofilament before recognizing the truth: there was no way that elegant piece of precision machinery was ever going to catch any fish for me. I put my Mr. Hyde’s Spincast 66 back in its rightful place and returned The Swedish Siren to the store whence it came, for some other more skillfully-thumbed fisherman than I to find.

I need to note at this point that with remarkable manliness and fortitude I have stoutly resisted the temptation and the blandishments of my fly-fishing neighbor. I am not getting into fly fishing. Part of my reluctance is the staggering cost of the equipment: except for that Swedish beauty, I’ve always regarded a $40 rod and reel combo as the upper limit of reasonable expenditure—if it catches fish, why spend more? Even a cheap fly rod costs three or four times that, not to mention the $80-100 for an entry level reel and the outrageously overpriced line. One hundred yards of fly line costs more than a few miles of monofilament. Then there is the arcana of flies, and the sniffs of disapproval from the purists who think that if you need to buy flies, well, that’s…well, OK…but....after all...

To the dedicated fly fisherman, the sort of person who has three copies of A River Runs Through It in his video library and regards a trip to Orvis as equivalent to a pilgrimage to Mecca, buying flies is like buying sex. Even where it’s legal, it is justNot Done, except by those who are truly desperate. Nevertheless, there is no way I am going to shell out the bucks for fly tying equipment. I already have enough expensive hobbies. I will continue to use worms, minnows (and crayfish when I can get them), and spinning gear, and let the chips fall where they may. Since God made fish with an innate desire to eat real creepy-crawlies, why offer them fake ones? Especially fake ones at $2 apiece, lobbed at them with $400 worth of gear, when a $30 rod and reel baited with nightcrawlers at $1.50 a dozen will do the job so nicely?

In 1999, when my father in law died, he left behind a good deal of old fishing tackle, including a short all-steel spinning rod made by “Tru-Temper,” probably dating from the early 1950’s, like the Spincast 66. Now, there was an obvious match: a vintage rod and a vintage reel. Starting with the 2000 fishing season I used that combination extensively, quickly losing count of the number of smallmouth bass it caught in the ensuing two years of the “marriage.”

But there are hazards in using old equipment, especially when it has high sentimental value. If something happens to it, it’s gone and the memories are all you have left. Last season, coming off the New after a very productive afternoon of wade fishing, I discovered to my horror that the acorn nut holding the crank handle of my Spincast 66 in place had fallen off and was at the bottom of the New, God alone knew where. It was only by sheer dumb luck that I hadn’t lost the crank handle as well! That thought really shook me up. Major parts for 50-year old reels aren’t easily obtained.

But, thought I, surely an acorn nut can be had at any hardware store; I can restore it. Yes, acorn nuts are sold in hardware stores, but apparently not in whatever peculiar thread profile South Bend was using in the 1950’s. I never did find a nut that would fit. I briefly toyed with the idea of buying a standard nut and re-threading the crank, but discarded that as an insult to my old pal.

I did manage to force-fit a nylon nut into place. This held the crank on, and since the nylon was soft it didn’t ruin the threads, but it was, well, plastic. Not only did it look odd, it was wrong. There’s nothing plastic on that reel. It’s made from die-cast and machined parts, mostly aluminum with some steel. Putting a plastic nut onto it was only marginally preferable to not fixing it at all. I wanted a replacement acorn nut, and nothing would do but one from a Spincast 66.

A non-functional Spincast 66 might still have the requisite nut. Thank God for E-Bay: the phrase “South Bend Reel” in their search engine produced numerous hits, and lo and behold, hit #3 was...a BRAND NEW Spincast 66, still in the original box! Needless to say I was happy to bid and even happier to win the auction at an absurdly low price. I’d have paid five times as much just to get a replacement acorn nut, let alone a whole reel. The lady I bought it from was kind enough to throw in a Spincast 77 fit only for parts for an extra dollar.

The “new” Spincast 66, which must be close to 50 years old, is absolutely identical to my old friend. Its glistening acorn nut promptly came off and went onto Mr. Hyde’s gift. The acorn nut from the Spincast 77 (which has the same threading, but a slightly different shape) went on the “new” reel. Mr. Hyde’s reel, restored to as close to original condition as it can get, is now resting in honored retirement in a factory box, wrapped in original factory paper, alongside an original factory instruction sheet. The “new” Spincast 66 has taken its place on my father in law’s Tru-Temper rod, and this Spring, when the bass start biting, it will begin its career. The King is dead; long live the King!

Mr. Hyde's true gift wasn’t a used fishing reel. It was encouragement and an opportunity to try again: with that came success, and with that came commitment to a lifelong hobby. I’m still more of a hunter than a fisherman, but nowadays, whenever I’m out on the water, Mr Hyde, wherever else he may be, is right there alongside me.

And oh, yes, that’s not all: the VIVIF is back in production!

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |