BANG! YOU’RE DEAD!

A Primer on Humane Animal Killers

Anyone who’s slaughtered food animals knows the drill: first the beast is stunned with a blow to the head, then the large blood vessels in the neck are severed and the animal bled out. (In case you don't know, here's how it's done, courtesy of the Oklahoma Extension Service .)

In the Good Old Days, stunning was done with a huge mallet, which required great strength, and great skill, to use effectively. A bad blow would cause pain and suffering and might result in a 1000-pound bull with a heck of a headache and a target for his rage…the incompetent slaughterman.

Beginning in the mid 19th Century, an offshoot of firearms technology rendered the poll-hammer obsolete. “Humane killers” permit clean, effective, and rapid slaughter even by relatively weak or inexperienced people. Victorian sensibilities, coupled with increasingly stringent firearms laws and the rise of industrial-assembly-line meat packing plants, ensured these devices had a ready market.

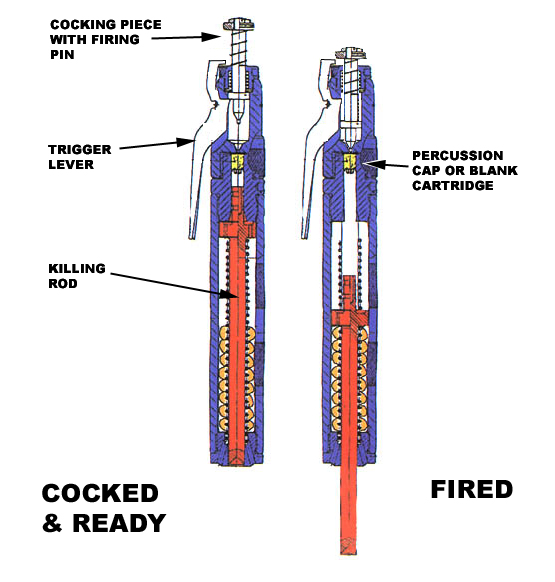

Two basic types exist: the “free bullet” and the “captive bolt.” The latter drives a hardened steel killing rod with a blank powder charge instead of a bullet.

Two basic types exist: the “free bullet” and the “captive bolt.” The latter drives a hardened steel killing rod with a blank powder charge instead of a bullet.

The term "captive bolt" is derived from the fact that the rod remains attached to the firing apparatus. A number of companies still make them (a Schermer model is shown above) for the meat trade: a captive bolt killer (or stunner) is more suited to industrial use for reasons of safety, since no actual bullet is fired. They are also not "firearms" under the law and require no special paperwork, even in restrictive locations.

The captive bolt killer is powered by a blank cartridge (of the type used in nail guns) or a very large percussion cap, which come in different levels of power depending on the application. The explosion of the cartridge drives a piston attached to a rod, driving it into the animal’s brain, killing it. A modified version has a "mushroom" shaped striking rod: the blunt end stuns the animal, which is then actually killed by severing the carotid arteries and allowing it to bleed out. Cartridge type killers are suited to small volume operations, but high volume slaughter plants use pneumatically-powered models, which are faster to recharge.

Free-bullet killers are essentially small-caliber pistols specialized for the one task of putting animals down. As the name implies, these actually fire a bullet into the animal's head. Placement of the muzzle in exactly the right position is critical, and if properly done, a large animal such as a steer or a horse can reliably be "put down" with surprisingly small bullets.

Free-bullet killers are essentially small-caliber pistols specialized for the one task of putting animals down. As the name implies, these actually fire a bullet into the animal's head. Placement of the muzzle in exactly the right position is critical, and if properly done, a large animal such as a steer or a horse can reliably be "put down" with surprisingly small bullets.

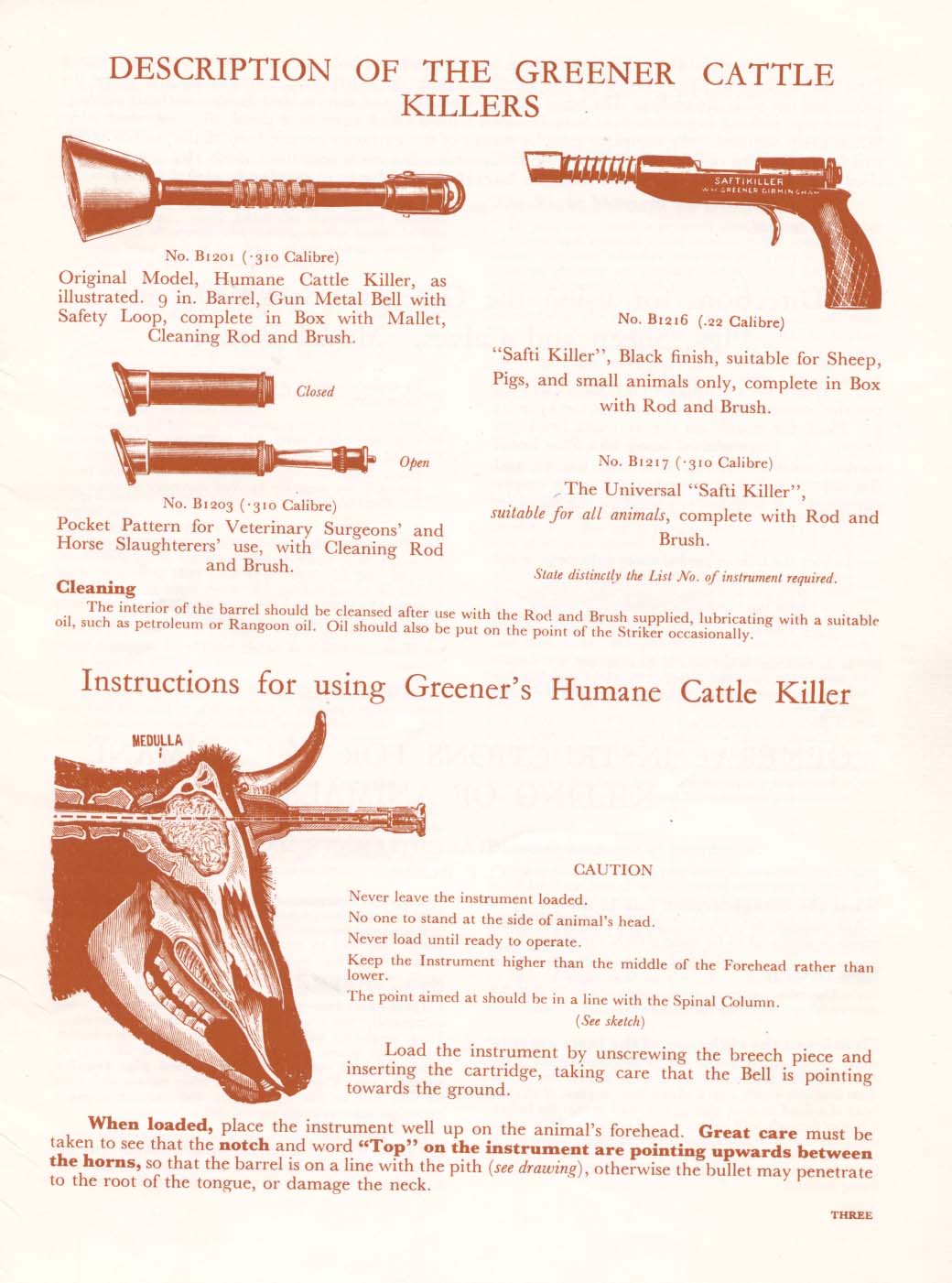

“Greener’s Humane Horse (or Cattle) Killer” was one of the very first practical free bullet killers. It was introduced in 1865, i.e., almost as soon as practical self-contained ammunition came onto the market. The device was a "smashing" success, manufactured well into the 1960’s. The firm has recently re-introduced a nearly identical device, the "Mark II" Pocket Model. Mr. Graham Greener, the current Director of the W.W. Greener firm, tells me that older Humane Horse Killers can be rechambered to .32 ACP, which is the cartridge used in the Mark II.

Greener's Humane Killers are the best known, though Greener was not the only manufacturer of free-bullet killers. Collectors of veterinary paraphernalia regard the Greener Humane Killer as a very desirable item, almost the "Holy Grail" of this rather specialized field of collection. Prices for a good one, especially the Pocket Model, range from $250 to $400 depending on condition and whether the original carrying case is included. The Folding Veterinarian's Pocket Model, shown below, was small enough to carry in the vet’s little black bag: in the first half of the 20th Century virtually every country and racecourse veterinarian carried one. Not many people realize it now, but well into World War Two, most European armies still had cavalry units; and they relied on horses to haul supplies and heavy weapons. Hence, there were soldiers whose job was to tend to them, and when needed, to put them down. The Pocket Model Humane Killer was standard issue to farriers and vets in the British Army.

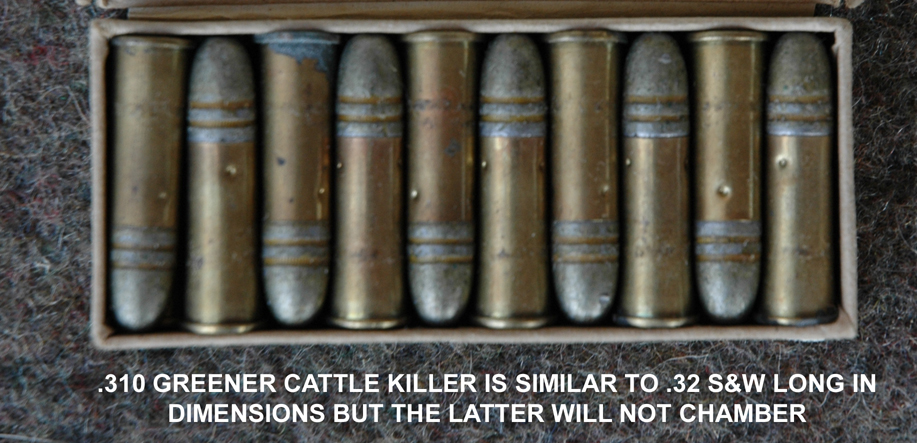

A Pocket Model Killer even has been a prop in a TV show: in an episode of the old TV series All Creatures Great & Small , the protagonist "James Herriott" pulls it from his little black bag and puts down an ailing horse. Even today, Greener Killers are being used in the United Kingdom by veterinarians who have a supply of ammunition or who have had theirs rechambered. The case is essentially a shortened version of the ".310 Cadet" round used in small-frame Martini rifles. The .310 Cadet isn't easy to find, either, but .310 Cattle Killer is far scarcer: thanks to its limited use it was never produced in large amounts, and hasn't been made for decades. Existing stocks were used up, and as UK gun laws grew progressively stricter in the 1960's and 70's, users switched to the easier-to-license captive bolt killers.

I was fortunate enough to be given a full box of twenty .310 Cattle Killer cartridges by a friend in the UK some years ago. Superficially it's very similar to the .32 S&W Long, though the dimensions are different enough that the latter will not chamber in the Killer. It has a "heeled" bullet of the same outside diameter as the cartridge case, with a waxy exterior lubricant. The .32 S&W Short will chamber in my Killer and so will a .32 ACP. I have never fired either one of these "alternates" and I'm certainly not about to shoot off any of my .310 Cattle Killer! The ammunition is rare enough that a full box is worth substantially more than the Killer itself is!

I was fortunate enough to be given a full box of twenty .310 Cattle Killer cartridges by a friend in the UK some years ago. Superficially it's very similar to the .32 S&W Long, though the dimensions are different enough that the latter will not chamber in the Killer. It has a "heeled" bullet of the same outside diameter as the cartridge case, with a waxy exterior lubricant. The .32 S&W Short will chamber in my Killer and so will a .32 ACP. I have never fired either one of these "alternates" and I'm certainly not about to shoot off any of my .310 Cattle Killer! The ammunition is rare enough that a full box is worth substantially more than the Killer itself is!

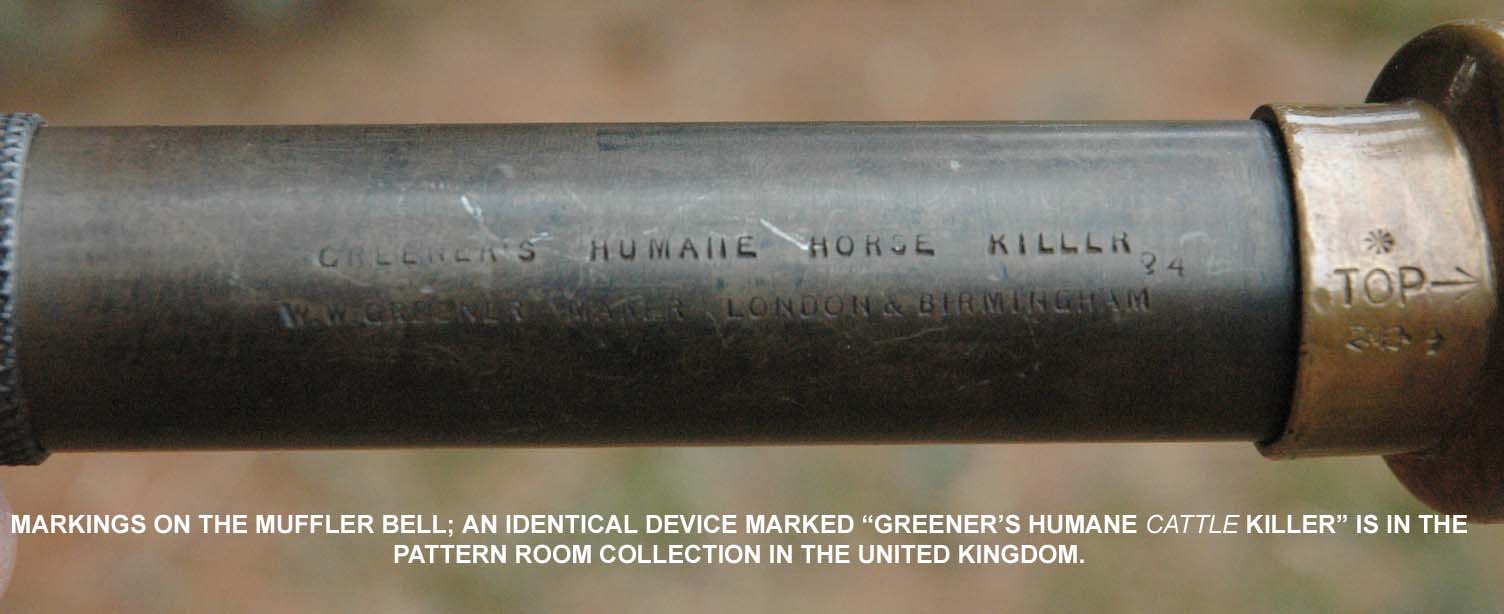

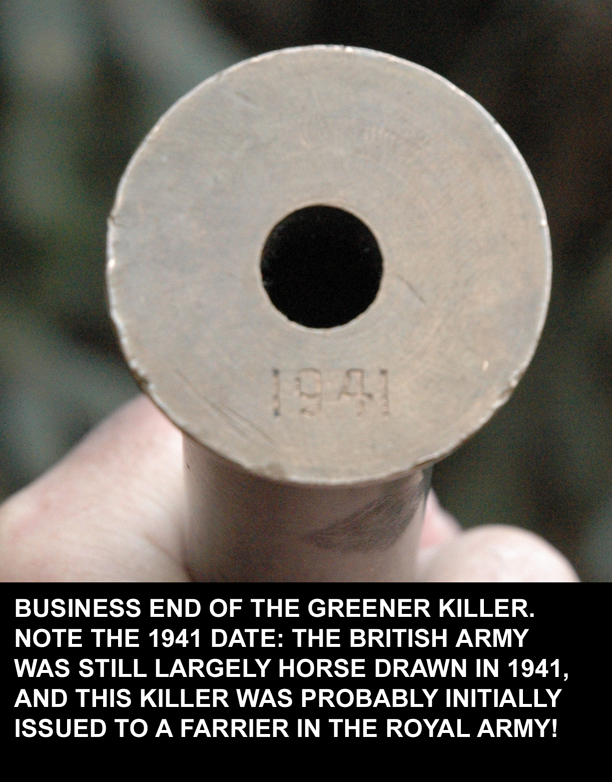

The Killer has a muffler bell on the end. In the picture above, everything is stowed inside the muffler bell: the Pocket Model is designed in such a way that everything fits into a package not much more than 6" long.

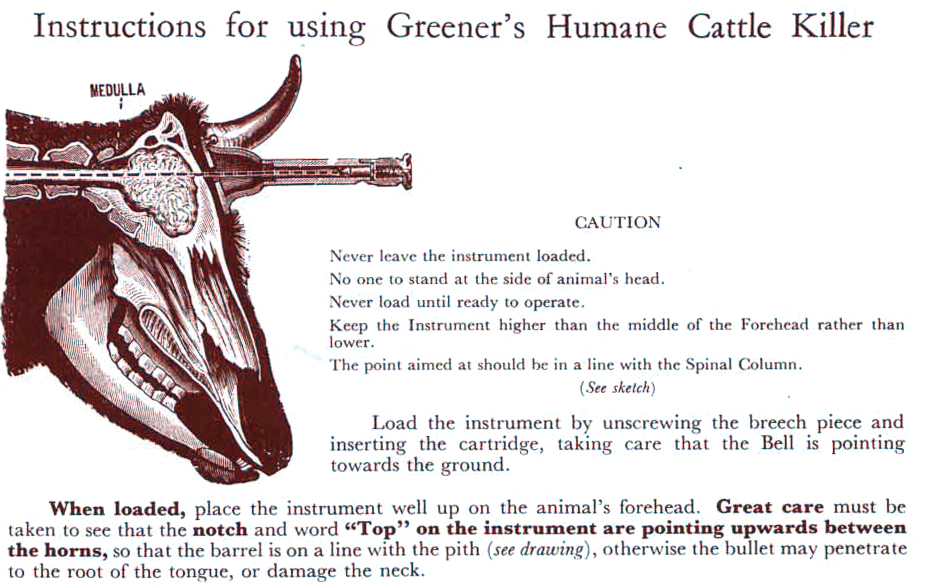

The firing mechanism is a spring-loaded firing pin screwed onto the breech after a cartridge is inserted. The bell is placed on the animal’s head, and the firing pin struck smartly with the “mallet” to discharge the round.

Even though they weren't regarded as firearms, the Killers had to be tested at Birmingham Proof House. They bear the appropriate Birmingham proof marks, including nitro proof stamps, on the barrel; and they have serial numbers. If the four-digit serial number on mine (made in 1941, seventy-six years into the production run) is any indication, clearly they had a limited market and weren't a high-volume product.

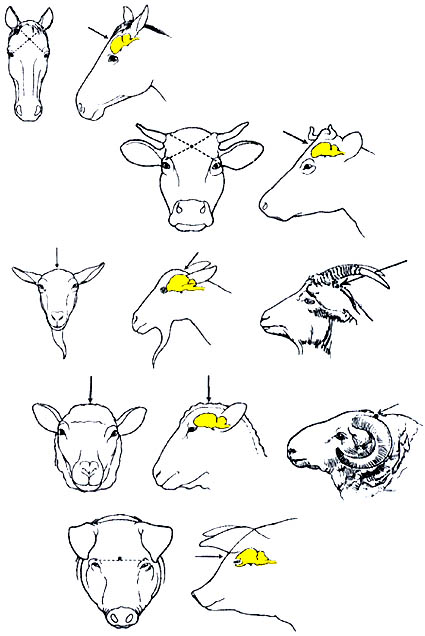

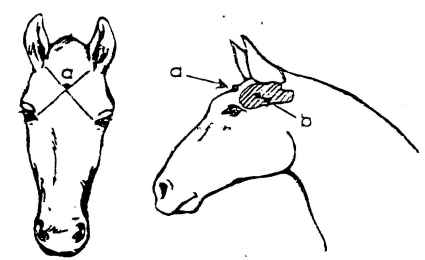

Every hunter and defensive shooter is taught the mantra: "Shot placement is the most important consideration." This is no less true in the somewhat more technical exercise of slaughtering. Some indication of the way the Killer is used can be gained from the images above, and just to make sure everyone knew, Greener included in the package a set of diagrams showing the proper positioning of the killer on various species.

Every hunter and defensive shooter is taught the mantra: "Shot placement is the most important consideration." This is no less true in the somewhat more technical exercise of slaughtering. Some indication of the way the Killer is used can be gained from the images above, and just to make sure everyone knew, Greener included in the package a set of diagrams showing the proper positioning of the killer on various species.  The "sweet spot" differs in different species. Smaller animals such as sheep and goats are shot in the top of the head, but for horses and cattle the proper positioning is determined by drawing lines between the ear and the opposite eye, and then placing the end of the muffler slightly above the point where they cross. Given proper placement, the animal died instantly, or was at least stunned enough to be bled out. In cattle the aim was to "pith" the beast, by driving the bullet through the brain and into the upper end of the spinal cord.

The "sweet spot" differs in different species. Smaller animals such as sheep and goats are shot in the top of the head, but for horses and cattle the proper positioning is determined by drawing lines between the ear and the opposite eye, and then placing the end of the muffler slightly above the point where they cross. Given proper placement, the animal died instantly, or was at least stunned enough to be bled out. In cattle the aim was to "pith" the beast, by driving the bullet through the brain and into the upper end of the spinal cord.

As with captive bolt killers, cartridges of different power were made for different size animals. Greener made several other versions of humane Killers, including a special model just for use on dogs!

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |