YOU'RE BEING PLAYED: HOW OUTDOORSMEN ARE TRICKED BY ADVERTISING

The American outdoors industry thrives on dissatisfaction. This is assiduously cultivated by advertising whose purpose is to make shooters, hunters, and fishermen uncomfortable with—if not downright ashamed of—the guns and gear they already have, to get them to buy something else. Manipulation of consumers is an established art that’s been perfected over decades to sell everything: cars, soap, prescription medications, clothing fashions and every other commodity; but outdoors equipment is an especially fertile field.

There’s something buried deep in the human psyche that ad men understand perfectly and exploit with consummate skill. They’re able to convince outdoorsmen that if they will just buy something “new” (even when it’s patently no different than the “old” in any significant sense) whatever their troubles may be, they will be over. By fostering and exploiting the flocking behavior of outdoorsmen advertisers can make them dance to any tune the companies who employ them want.

Walking through any large outdoors store is like walking through a catalog. Even though they all sell the same stuff and use the same gimmicks, the tricks work every time to convince the customer that what he owns and has used successfully in the past is hopelessly, completely, and utterly obsolete; but if he will only buy this product, he will catch/kill the biggest, best, and/or finest example of ________________ (fill in the species) imaginable, every time, and without fail. Until, of course, next year when another “new” product comes out that makes all the stuff he just bought obsolete. Honestly, sometimes you have to ask yourself how Native Americans ever caught fish or killed deer. They lacked everything the present-day outdoorsman is told is essential for success. They had no GPS units, no depth or fish finders, no compound bows, no scent pads for their insulated boots (no boots at all, for that matter), no electric socks, no heat-detection devices, no trail cameras, no in-line rifles using 350-grain sabot projectiles over 150-grain Pyrodex pellets, no scopes, no rangefinders, no Royalex canoes, no climbing tree stands, no range-finding scopes, no nothin'. Surely they must have starved?

The early North American Colonists and the pioneers who pushed westward weren't much better off than the indigenous people. They were stuck using flintlock rifles—sometimes even smoothbored muskets—shooting round balls. They had to catch fish on simple hooks using cotton twine and they used live bait, of all things. They didn’t have the Never-Fail-Catch-One-Every-Time lures we’re told that every Serious Fisherman uses. Catalog ads drive the nail to the board, slamming home the message that such things are absolutely necessary; that by using them you will not only succeed but will do so with far less work and effort than otherwise. Most gratifyingly, the pitch is that you’ll have bragging rights when you show up at the check station or the weigh station with your "monster buck" or your finny "hawg".

Cable TV has been a bonanza for the hucksters, allowing them to float enticing stuff past people's noses in very carefully edited footage. The dreadful "hunting" and "fishing" shows on the Boob Tube are long commercials for the dozens of sponsors whose logos are on display on the presenters’ clothes, boats, and everywhere else. These ghastly programs use the most effective advertising tool ever devised—television—to gull novices and experienced people alike into thinking that they’re failures if they don’t have what the guy on the screen is using. Alas, like the latest Day-Glo, electric buzz-bait is alleged to be, this sort of advertising is nigh irresistible. Hunters and fisherman snap at the bait like a hungry bass spotting a crayfish.

Cable TV has been a bonanza for the hucksters, allowing them to float enticing stuff past people's noses in very carefully edited footage. The dreadful "hunting" and "fishing" shows on the Boob Tube are long commercials for the dozens of sponsors whose logos are on display on the presenters’ clothes, boats, and everywhere else. These ghastly programs use the most effective advertising tool ever devised—television—to gull novices and experienced people alike into thinking that they’re failures if they don’t have what the guy on the screen is using. Alas, like the latest Day-Glo, electric buzz-bait is alleged to be, this sort of advertising is nigh irresistible. Hunters and fisherman snap at the bait like a hungry bass spotting a crayfish.

The constant theme of these sales pitches is that whatever they’re peddling will enhance the "authentic outdoors experience," but as nearly as I can tell, the “authentic outdoors experience” as presented by the Outdoor Channel and its ilk consists of sitting in an elevated permanent blind in Alabama or Texas (air conditioned, of course, and with Internet service) shooting pen-raised whitetails with a .300 Win Mag at a feeder thirty yards away. Of course, the flubs, missed shots (yes, even at 30 yards), wounded animals, lost fish, and other gaffes aren’t shown. Those things are indeed part of the “authentic outdoors experience” as any hunter or fisherman knows, but they don’t serve the purpose of selling stuff.

Fleecing the gullible by inducing self-doubt extends not just to guns, but to all kinds of gear, sometimes to the point of sheer idiocy. Not too long ago I saw something on the Outdoor Channel that really floored me. You can now buy a variety of kid-sized ATVs. I mean for little kids, advertised as suitable for 3 year olds ! They're small-scale versions of Dad's with limited horsepower, and most come comes with a "Daddy" cord so that if the tyke motors off on his own, the machine stops. The breathtaking and more or less explicit implication of this ad is that without an ATV a kid can't hunt "properly," i.e., the way Dad does it. And…of course, eventually he'll graduate to a "real" ATV for "real" hunting. After all, how can someone reasonably be expected to hunt a 150-acre Virginia woodlot without a motor vehicle?

Now, I will freely admit that many technological products are useful. I use them myself. After all, we don’t use atlatls or pit traps the way our Pleistocene ancestors did because we have better technology such as rifles. Modern well-designed gear can keep you comfortable in the woods. A GPS can help you find your way home or back to the site of a kill. No one can object to any of this. But it seems to me that there has to be a balance wherein the technology we use doesn’t give the hunter or fisherman such an overwhelming advantage that a game animal or fish never escapes. Unfortunately this line is never drawn in advertising, quite the reverse. Most of what’s being hawked diminishes the essential nature of the outdoors experience. At the very least it reduces the amount of skill, woodcraft, or wit needed to be good at hunting or fishing: and that is not a good thing. Just why are we in the woods or on the river if not to match wits with our prey, and may the best species win? Hunting and fishing aren’t life-or-death matters for us, as they were to indigenous people or even the pioneers: they are recreation. If there’s no challenge presented to the outdoorsman, what’s the point?

It baffles me that reasonably intelligent people—and most of the folks I meet in the field pass that test, I think—can be suckered so often and so easily. If someone has been catching fish for decades with a 30-year-old reel and discount-store monofilament, how can he be so easily led to believe that he absolutely needs a brand new reel and line costing 20 times as much money as he has in his existing gear? If he's been successful with Lure A, how can he accept on its face the statement that Lure A is no longer good enough, he must have Lure B or he won't continue to catch fish? If he's been killing deer for years with his Grandfather’s lever action .30-30, and the conditions of his hunt haven't changed, why does he immediately accept the notion that can’t do without a “tactical grade” .300 WSM or a 6.5 Creedmoor next season?

I believe it’s wrong to think of outdoors sports merely as  conduits through which money can be funneled ad infinitum from consumers to gear makers and advertisers. They are more than that. Moreover, hunting and fishing aren’t “competitive sports” except in the sense that the hunter or fisherman is competing with the animals or fish. But if someone can be convinced that to think he’s competing with other hunters or fishermen, the innate human desire to “get an edge” kicks in. He’ll then be ready to spend big bucks to get that edge. If he can be led to believe that if he has killed a small deer or caught a fish that isn’t record size, he’s failed, then the next question is why he failed; and how can he succeed next time? Advertising gives him the answer, and it’s the same answer every time: buy new stuff because what you have is inadequate.

conduits through which money can be funneled ad infinitum from consumers to gear makers and advertisers. They are more than that. Moreover, hunting and fishing aren’t “competitive sports” except in the sense that the hunter or fisherman is competing with the animals or fish. But if someone can be convinced that to think he’s competing with other hunters or fishermen, the innate human desire to “get an edge” kicks in. He’ll then be ready to spend big bucks to get that edge. If he can be led to believe that if he has killed a small deer or caught a fish that isn’t record size, he’s failed, then the next question is why he failed; and how can he succeed next time? Advertising gives him the answer, and it’s the same answer every time: buy new stuff because what you have is inadequate.

It’s instructive to compare a current sporting goods catalog to the old Herter's catalogs of 50-60 years ago. George Leonard Herter was in some ways ahead of his time, but his catalogs still reflected far more the practical side of outdoorsman ship than do those of the current companies. Leaving aside color images and flashy copy used today there's also a difference in the philosophy prevalent in the two eras. GLH wanted to become rich by helping people develop their natural predatory talents; the big catalog companies today make money by convincing them that they have no natural talent; and that Product X will make up for that lack.

Some Examples

Advertising is especially effective when it comes to gun sales. Guns are more or less immortal given even modest care; a rifle that’s been used by three or even four generations of a family is by no means unusual. Since gun manufacturers can only stay in business by selling more guns they turn to the hucksters for help. There are some standard “tricks of the trade” that consistently work. They apply to nearly any kind of outdoors gear but the best and most egregious examples are seen in gun and ammunition sales. Here are a couple of them:

The “New” Scam

One really effective tactic to get people to buy new stuff, especially ammunition, is the introduction of purportedly “new” calibers. The fact is that there hasn’t been anything truly innovative with respect to ammunition since the invention and introduction of smokeless powder in the 1880’s; the last genuine innovation in American sporting ammunition was the introduction of the .30-30 in 1895.

But if the targets of advertising campaigns can be convinced that there are things that are “new and improved” sales will continue. Sales are the point; without sales ammunition and gun companies go under. This trick is played all the time.

A very good fairly recent example of how well it works is the introduction of the .17 caliber rimfire rounds. If there were a better exemplar of the “solution in search of a problem” than these I have yet to see it. The market for small caliber rifles and handguns is finite: by the time someone has acquired a few rimfire guns what more is there to sell him? The average shooter or hunter likely has three or four rimfire rifles and/or handguns, many have more than that. How many people really “need” a new plinker or hunting rifle, with several already in the safe? Maybe a son, daughter, niece or nephew is to be given a rifle, but that can take years to happen. Worse, from the point of the gun companies, very often the gun is one that’s already been passed down from an older generation. That situation means stagnant sales, a threat to the livelihood of everyone who works for the companies and the gun press. How can Remchester and its ilk stay in business? What would gun writers have to write about in the next issue of every magazine? To solve this dilemma the “new caliber” ploy gets trotted out. In essence this is exactly the same way laundry detergent is sold: change a minor ingredient, tart up the box a bit, and tell everyone how much better it is than that old detergent that didn’t do anything except clean clothes.

A very good fairly recent example of how well it works is the introduction of the .17 caliber rimfire rounds. If there were a better exemplar of the “solution in search of a problem” than these I have yet to see it. The market for small caliber rifles and handguns is finite: by the time someone has acquired a few rimfire guns what more is there to sell him? The average shooter or hunter likely has three or four rimfire rifles and/or handguns, many have more than that. How many people really “need” a new plinker or hunting rifle, with several already in the safe? Maybe a son, daughter, niece or nephew is to be given a rifle, but that can take years to happen. Worse, from the point of the gun companies, very often the gun is one that’s already been passed down from an older generation. That situation means stagnant sales, a threat to the livelihood of everyone who works for the companies and the gun press. How can Remchester and its ilk stay in business? What would gun writers have to write about in the next issue of every magazine? To solve this dilemma the “new caliber” ploy gets trotted out. In essence this is exactly the same way laundry detergent is sold: change a minor ingredient, tart up the box a bit, and tell everyone how much better it is than that old detergent that didn’t do anything except clean clothes.

The first of the .17’s, the .17 HMR, was touted as the answer to a sportsman’s prayer though it really did nothing that wasn’t already being done effectively by existing rounds. That didn’t matter because its one and only one purpose was selling more rifles and handguns. Not better ones, just “new” ones. The “new” caliber was ballyhooed and puffed by fawning “reviews” in the gun press, the writers waving a lot of pizzazz to dazzle potential buyers. The .22 Magnum, on whose case the .17 HMR was based—it’s nothing more than a necked-down .22 Magnum—had been introduced 60 years before, with the promise that it would be “better” than the .22 Long Rifle. Time has shown that the price of .22 Magnum is wildly out of proportion to any improvement in performance, and it’s far too powerful for small game. Its past success has come through heavy advertising, but its star is beginning to fade as the .17 HMR gets the same “new caliber” puffing its ancestor did.

Another example of how advertising can make or break a caliber is the 6.5 Creedmoor. Generally 6.5mm rounds have been lackluster performers in the US market: the parlous state of the .260 Remington, introduced about 25 years ago, attests to this. The 6.5 Creedmoor was introduced 10 years later, and while it’s no doubt a fine round in its own right, it’s certainly no better than the .260 Remington. Reading the gun magazines, however, you’d think it was brought to Earth on a golden cloud to answer the prayers of hunters and target shooters for a “really effective” 6.5mm round—even though such a thing already existed. You can hardly open a magazine or access a website without hearing the hosannas of praise for the Creedmoor. If the .260 had had such puffery attached to it, it might well have been more of a success than it has been, but it was left to languish and its disappearance is all too predictable. The stupendous advertising blitz for the Creedmoor ensures its success, until something along the lines of the 6.35 Whiz-Bang Super-Collider comes along to replace it.

Sometimes—not often—this film-flam act doesn’t work, but it works often enough that it’s used regularly. The 5mm Rimfire, .256 Winchester and the .22 Jet all were flops because even the dimmest and most easily gulled potential buyer could see that those “new” calibers did nothing that needed to be done. But anyone who doubts this “new caliber” trick is usually effective should check out the latest issues of the gun magazines, trumpeting the “.350 Legend” caliber or the “Federal Fire stick” for muzzle-loaders, to name just a couple of recent examples. Both are flying off the shelves.

The “Filling The Gap” Trick

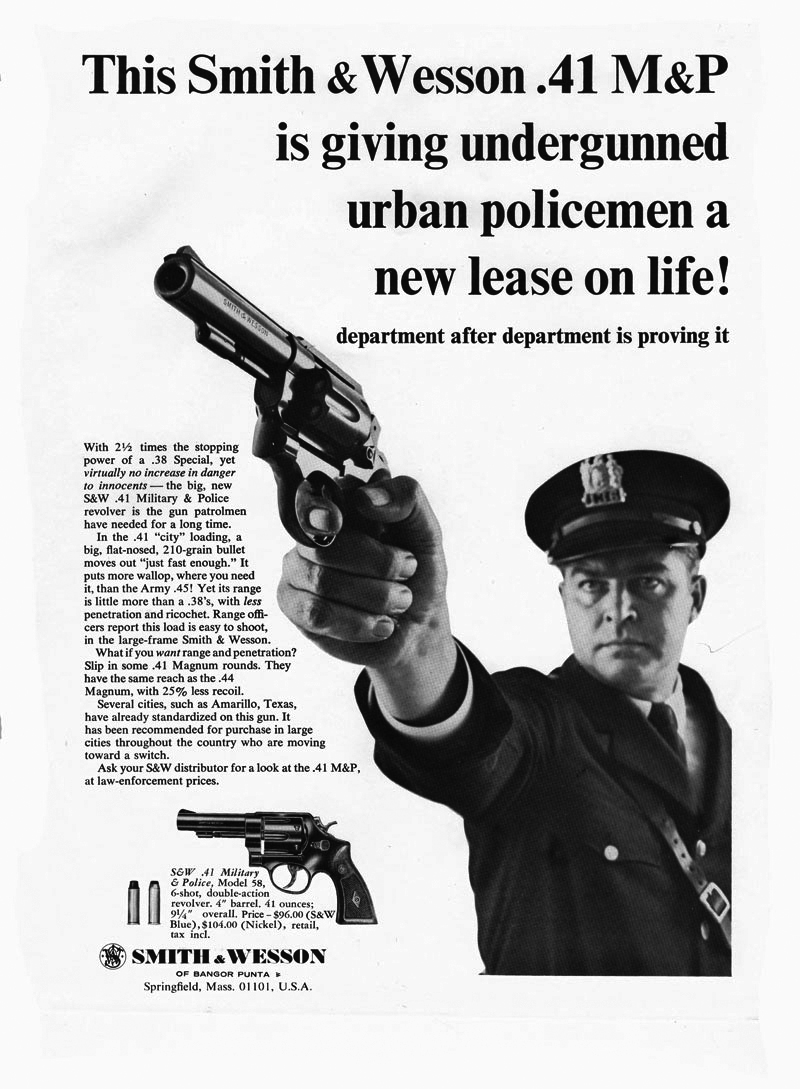

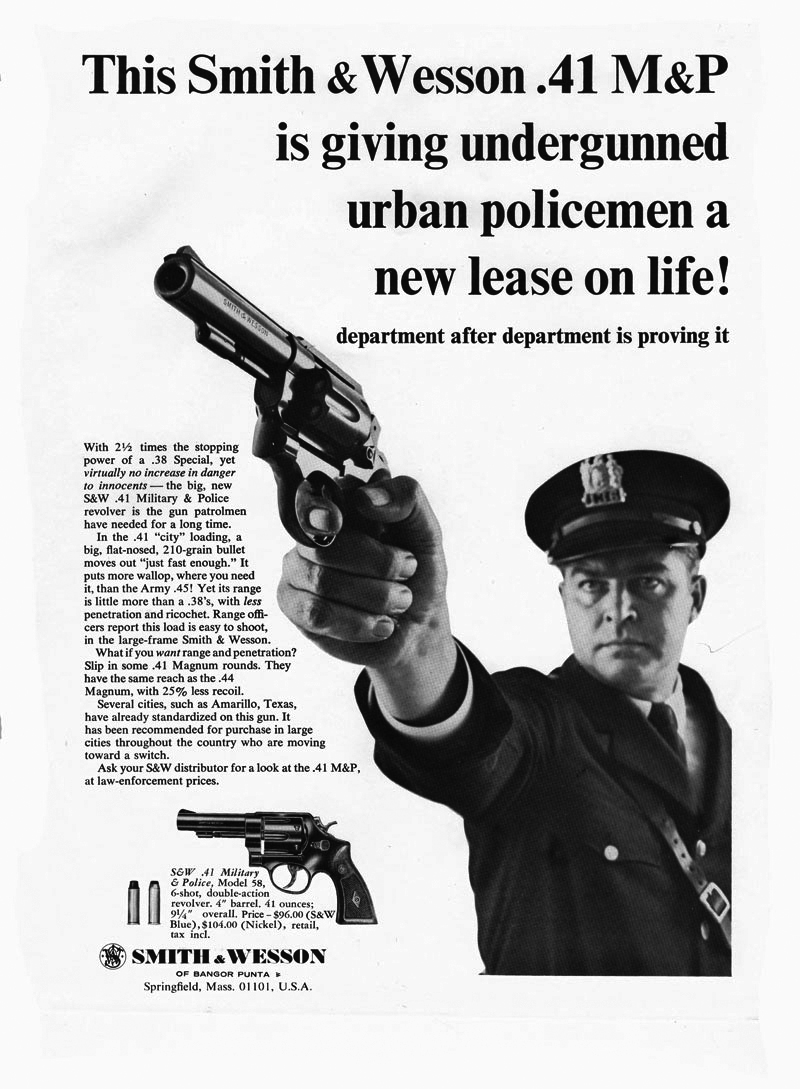

Another favorite tactic is the “fill the gap” approach, really a variant on the “new caliber” ploy. If caliber A and caliber B have bullets whose diameters are a tenth of an inch different, lo, there is a “gap” that presents an opening (ha, ha) for the advertisers. In no other way can one explain the success of the .40 Smith & Wesson handgun round: the 9mm and various .38 calibers use bullets 0.355-.358” while the various .45-calibers use one that’s 0.452-.454”. That tenth-of-an-inch “gap” is wide enough to drive an advertising campaign through it.

There have been several calibers that shoot bullets 0.410” +/- (in the Metric system, 10mm). Most have been commercial failures not because they weren’t effective, but because their advertising wasn’t. It’s instructive to compare the fates of the 10mm Auto and the .41 Magnum to that of the .40 S&W. The 10mm Auto is so powerful that FBI agents had a hard time shooting it well. To address this issue the “new”.40 S&W, was brought out which very conveniently simultaneously “filled the gap” between 9mm and .45. It has succeeded not so much on its merits as because it gets great press. It won’t do anything that can’t be done with the 1905-vintage .45 ACP but that round has been around for more than a century and is, let’s face it, passé. Not exciting. Not something to shout about. Doesn’t “fill the gap.”

There have been several calibers that shoot bullets 0.410” +/- (in the Metric system, 10mm). Most have been commercial failures not because they weren’t effective, but because their advertising wasn’t. It’s instructive to compare the fates of the 10mm Auto and the .41 Magnum to that of the .40 S&W. The 10mm Auto is so powerful that FBI agents had a hard time shooting it well. To address this issue the “new”.40 S&W, was brought out which very conveniently simultaneously “filled the gap” between 9mm and .45. It has succeeded not so much on its merits as because it gets great press. It won’t do anything that can’t be done with the 1905-vintage .45 ACP but that round has been around for more than a century and is, let’s face it, passé. Not exciting. Not something to shout about. Doesn’t “fill the gap.”

The .41 Magnum was brought out in 1964 ostensibly to “fill the gap” between the .357 Magnum and the .44 Magnum. It was supposed to give police officers something better than the then-standard .38 Special. Today it hangs on—barely—because it has a few diehard fans. It can’t do anything that the .44 Magnum (or even a hot .44 Special) can’t do; as sure as the sunrise the time is coming when it will be discontinued.

The "new" .350 Legend has been brought out to "meet the need" of hunters in states that allow straight-walled cartridge in the "primitive weapons" season. Winchester is pushing it very hard in every gun magazine published even though it's little more than an updated version of the old .351 Self-Loader. It will probably succeed thanks to advertising.

The "Modernity" Trick

Muzzle-loading guns and hunting gear provide an illustrative example of how this one works. The transformation of the concept of “primitive weapon seasons” to emulate the way the pioneers hunted has come about in the following way: picture a hunter out in the muzzle-loading deer season who has a nice buck present himself; but it’s outside the range of a Hawken-style .50 using 90 grains FFg under a round ball. He can't shoot that buck; it's beyond what he regards as the effective range of his rifle, so the ethical thing is not to shoot. Wistfully he watches the buck saunter away and is mired in regret and guilt because he couldn’t take the shot.

That’s when the “modernity” argument is most useful. Someone who falls for it is brought to believe that the problem is he’s using obsolete technology (which of course he is: that’s the whole point of a “primitive weapon season”). He didn’t get that deer because he’s using stuff his great-great-grandfather might have used. So his first response, conditioned by years of advertising about “modern muzzle-loaders” will be to sell his Hawken ASAP, replacing it with a brand-new scoped in-line rifle using sabot bullets. If next season he sees a buck that happens to be out of range for his new gun, his automatic response will be to buy yet another rifle, perhaps one that uses a bigger charge of pellets. Instead of learning how to work within the capabilities of the equipment he already has the hunter is told that he can "improve his chances of success” by buying something new that will surely do what his current hopelessly obsolete stuff won't. And he can be made to go on repeating this cycle endlessly, which is what puts the children of the equipment makers and their sales force through school.

The beauty of the “modernity” trick is that it can be worked over and over; and—as with cartridge rifles—it can be combined with a fictitious division between “entry-level” rifles and the ones serious hunters use. If a deer can be killed cleanly with a $250 rifle, is there really any need to spend $500 or more on a “new” one? Of course not, but once the pattern of newer-is-better is fixed in the hunter’s mind, sidelock guns give way to striker-fired in-lines using #11 percussion caps; those in turn are derided as having an “obsolete ignition system” and rifles using #209 primers take their place. Then those rifles are denigrated as having “exposed” breeches, a flaw no truly “modern” rifle would have. Out come the closed-breech break-open rifles. Percussion caps and even #209 primers give way to rifles with electronic ignition systems. Loading from the muzzle? Nonsense! A modern gun uses the “Firestick” that inserts into the breech and only the projectile has to be loaded from the muzzle. A breech loading "muzzle-loader," now that’s really modern! So, ad infinitum, the marketeers and the gun makers create dissatisfaction and sell more guns.

The beauty of the “modernity” trick is that it can be worked over and over; and—as with cartridge rifles—it can be combined with a fictitious division between “entry-level” rifles and the ones serious hunters use. If a deer can be killed cleanly with a $250 rifle, is there really any need to spend $500 or more on a “new” one? Of course not, but once the pattern of newer-is-better is fixed in the hunter’s mind, sidelock guns give way to striker-fired in-lines using #11 percussion caps; those in turn are derided as having an “obsolete ignition system” and rifles using #209 primers take their place. Then those rifles are denigrated as having “exposed” breeches, a flaw no truly “modern” rifle would have. Out come the closed-breech break-open rifles. Percussion caps and even #209 primers give way to rifles with electronic ignition systems. Loading from the muzzle? Nonsense! A modern gun uses the “Firestick” that inserts into the breech and only the projectile has to be loaded from the muzzle. A breech loading "muzzle-loader," now that’s really modern! So, ad infinitum, the marketeers and the gun makers create dissatisfaction and sell more guns.

This isn’t a fanciful or fictitious scenario. The power of advertising is so strong that I’ve bought near-new guns from people who had owned them a year or less, didn’t get a deer, then decided they weren’t "good enough." I once bought a beautiful T/C sidelock rifle that had fired no more than 10 rounds because the man who sold it to me was convinced that it was “worthless.” He’d gone out and bought a brand new in-line rifle and sold me his Hawken at perhaps 25% of its real value, not because I talked him down, but because he was so convinced of its inherent inferiority that he offered it to me at that price. In effect, the advertisers talked him down for me. Nothing had changed in the places he hunted or the deer he sought: but he was suckered by that nagging doubt the marketeers skillfully placed in his mind that somehow, if he had this one magical new rifle, he would be successful next season in setting the cross hairs on Old Mossyhorns, The Monarch Of The Forest. The notion of the “superiority” of various flavors of in-line muzzle-loaders has taken such a hold that you can hardly give away a sidelock rifle where I live; they’re immediately spurned as “obsolete.” Thompson-Center, once the premier maker of production sidelock guns, has stopped making them altogether. But my sidelocks have killed a lot of deer every bit as dead as any in-line would have done.

I repeat, commercial success depends on gullibility. This doesn’t only apply to muzzle-loaders. Some years ago I met a young man at a hunting skills workshop. He was anxious to kill his very first deer, so he had brought his brand-new bolt action rifle with him. It was chambered for…the .338 Winchester Magnum ! Now, the average whitetail buck in this part of Virginia runs perhaps 110-120 pounds on the hoof. A real monster might go as much as 200 pounds. He’d bought that cannon (well suited to hunting Kodiak bears) because, as he put it, “I wanted to make sure they didn’t run.” He’d been convinced he needed it by hype about the caliber’s “knockdown” power as well as stories on TV and in magazines about how “tough” whitetails are, how hard it is to kill Old Mossyhorns. His inexperience and credulity led him to swallow this tripe without questioning it at all. And—most importantly—to spend money on something he didn’t need.

What Should You Hunt? How Should You Hunt It?

There are “fashions” in the game we hunt. This too is driven by advertising. Hunters have been conditioned to look down on some species as “not worth hunting”; fishermen have been taught that some species of fish are “better” than others. The idea of some species being “noble” and others not allows sub-groups of hunters and fishermen to be created and pitted against each other.

Over and above the designation of some species as “better” than others, there are tricks to convince hunters that how they hunt these animals is important. Right now a red-hot topic pushed in magazines is “long range” hunting, which of course necessitates rifles capable of hitting an animal at ridiculous distances. This demands that the hunter buy newer, specialized rifles and scopes, not to mention the new calibers specifically targeted (ha, ha) at people who want to shoot a deer at 600 yards or more. Can’t do that with Dad’s old Model 1894 Winchester!

Over and above the designation of some species as “better” than others, there are tricks to convince hunters that how they hunt these animals is important. Right now a red-hot topic pushed in magazines is “long range” hunting, which of course necessitates rifles capable of hitting an animal at ridiculous distances. This demands that the hunter buy newer, specialized rifles and scopes, not to mention the new calibers specifically targeted (ha, ha) at people who want to shoot a deer at 600 yards or more. Can’t do that with Dad’s old Model 1894 Winchester!

Possibly the finest example of how a species can be dismissed as not being “serious” or “worth bothering with” is what has happened to squirrel hunting. Fewer and fewer people hunt squirrels today because they’ve been taught to believe they’re "kid's game," not worth serious attention. This is nonsense; but unless you live in some place where the tradition of squirrel hunting is strong enough to overcome the influence of the advertisers, you're likely to feel that squirrels aren’t really “game.” Furthermore even youngsters—for whom traditionally squirrels were the first animal pursued—are being indoctrinated in this false dichotomy.

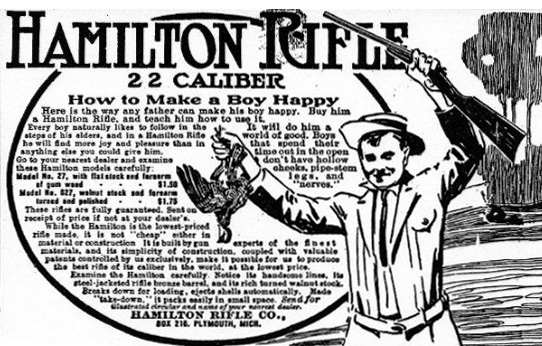

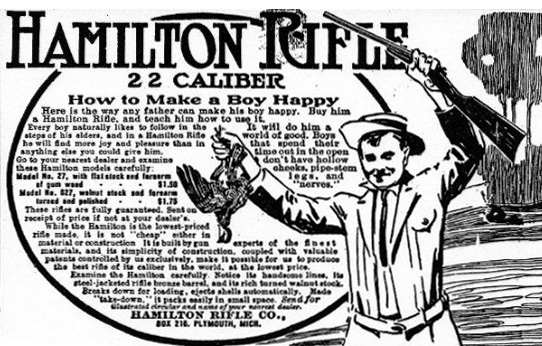

It used to be that a kid learned to hunt by tagging along with Dad, perhaps with his own .22 after a couple of years, and potted a squirrel or a rabbit now and then. When he got older he went off on his own to do it by himself. I have old advertisements from the early 20th Century showing beaming kids coming out of the woods holding dead critters they shot with their Hamilton Model 27 rifles. The kids are depicted wearing the everyday play clothes of the time: knickers, caps and neckties.

It used to be that a kid learned to hunt by tagging along with Dad, perhaps with his own .22 after a couple of years, and potted a squirrel or a rabbit now and then. When he got older he went off on his own to do it by himself. I have old advertisements from the early 20th Century showing beaming kids coming out of the woods holding dead critters they shot with their Hamilton Model 27 rifles. The kids are depicted wearing the everyday play clothes of the time: knickers, caps and neckties.

Since modern-day hunters universally believe that camouflage is essential to success, they will be happy to know that camouflage neckties are indeed available for their next formal evening in the deer stand. Amazon.com sells them.

Then there is turkey hunting. The spread of restrictions against lead shot has led to development of shot pellets made from very dense, hard materials like tungsten. All well and good, but the advertisers got hold of the legal requirements and turned them to the advantage of the sporting goods makers. Today we have “long range turkey loads” and the “challenge” to “serious” hunters to take birds at long distances using the pipsqueak .410 bore. Reams of puff pieces in the gun press have been touting this as the latest thing. Hunters dutifully step up, ditch their old reliable guns and buy new ones.

Ignore The Hype!

It can be argued that advertisers and gear manufacturers may just be making a buck and there's no reason why they shouldn't; but if the average outdoorsman would just think about what he’s being told, as well as how it's being said, and reflect on what his own experience has been, he will come to understand that 99.9% of what's in the catalog copy or on outdoors shows is pure, unadulterated, 24-carat baloney.

What I ask of my fellow outdoorsman is that they be to alert to the fact that they’re being “played” at every turn; and to urge them to think about how it’s being done. People need to cut through the hype and hooplah in the magazines and consider the realities of their own sporting environment and their real needs. There’s nothing wrong with wanting something, and buying it just for that reason. But it’s important to make purchasing decisions based on rational thought, not emotional responses to slick ads.

Remember: A thinking outdoorsman is a better outdoorsman, no matter what he uses.

|OPENING PAGE|

|SEASON LOGS |

Cable TV has been a bonanza for the hucksters, allowing them to float enticing stuff past people's noses in very carefully edited footage. The dreadful "hunting" and "fishing" shows on the Boob Tube are long commercials for the dozens of sponsors whose logos are on display on the presenters’ clothes, boats, and everywhere else. These ghastly programs use the most effective advertising tool ever devised—television—to gull novices and experienced people alike into thinking that they’re failures if they don’t have what the guy on the screen is using. Alas, like the latest Day-Glo, electric buzz-bait is alleged to be, this sort of advertising is nigh irresistible. Hunters and fisherman snap at the bait like a hungry bass spotting a crayfish.

Cable TV has been a bonanza for the hucksters, allowing them to float enticing stuff past people's noses in very carefully edited footage. The dreadful "hunting" and "fishing" shows on the Boob Tube are long commercials for the dozens of sponsors whose logos are on display on the presenters’ clothes, boats, and everywhere else. These ghastly programs use the most effective advertising tool ever devised—television—to gull novices and experienced people alike into thinking that they’re failures if they don’t have what the guy on the screen is using. Alas, like the latest Day-Glo, electric buzz-bait is alleged to be, this sort of advertising is nigh irresistible. Hunters and fisherman snap at the bait like a hungry bass spotting a crayfish.  conduits through which money can be funneled ad infinitum from consumers to gear makers and advertisers. They are more than that. Moreover, hunting and fishing aren’t “competitive sports” except in the sense that the hunter or fisherman is competing with the animals or fish. But if someone can be convinced that to think he’s competing with other hunters or fishermen, the innate human desire to “get an edge” kicks in. He’ll then be ready to spend big bucks to get that edge. If he can be led to believe that if he has killed a small deer or caught a fish that isn’t record size, he’s failed, then the next question is why he failed; and how can he succeed next time? Advertising gives him the answer, and it’s the same answer every time: buy new stuff because what you have is inadequate.

conduits through which money can be funneled ad infinitum from consumers to gear makers and advertisers. They are more than that. Moreover, hunting and fishing aren’t “competitive sports” except in the sense that the hunter or fisherman is competing with the animals or fish. But if someone can be convinced that to think he’s competing with other hunters or fishermen, the innate human desire to “get an edge” kicks in. He’ll then be ready to spend big bucks to get that edge. If he can be led to believe that if he has killed a small deer or caught a fish that isn’t record size, he’s failed, then the next question is why he failed; and how can he succeed next time? Advertising gives him the answer, and it’s the same answer every time: buy new stuff because what you have is inadequate.  A very good fairly recent example of how well it works is the introduction of the .17 caliber rimfire rounds. If there were a better exemplar of the “solution in search of a problem” than these I have yet to see it. The market for small caliber rifles and handguns is finite: by the time someone has acquired a few rimfire guns what more is there to sell him? The average shooter or hunter likely has three or four rimfire rifles and/or handguns, many have more than that. How many people really “need” a new plinker or hunting rifle, with several already in the safe? Maybe a son, daughter, niece or nephew is to be given a rifle, but that can take years to happen. Worse, from the point of the gun companies, very often the gun is one that’s already been passed down from an older generation. That situation means stagnant sales, a threat to the livelihood of everyone who works for the companies and the gun press. How can Remchester and its ilk stay in business? What would gun writers have to write about in the next issue of every magazine? To solve this dilemma the “new caliber” ploy gets trotted out. In essence this is exactly the same way laundry detergent is sold: change a minor ingredient, tart up the box a bit, and tell everyone how much better it is than that old detergent that didn’t do anything except clean clothes.

A very good fairly recent example of how well it works is the introduction of the .17 caliber rimfire rounds. If there were a better exemplar of the “solution in search of a problem” than these I have yet to see it. The market for small caliber rifles and handguns is finite: by the time someone has acquired a few rimfire guns what more is there to sell him? The average shooter or hunter likely has three or four rimfire rifles and/or handguns, many have more than that. How many people really “need” a new plinker or hunting rifle, with several already in the safe? Maybe a son, daughter, niece or nephew is to be given a rifle, but that can take years to happen. Worse, from the point of the gun companies, very often the gun is one that’s already been passed down from an older generation. That situation means stagnant sales, a threat to the livelihood of everyone who works for the companies and the gun press. How can Remchester and its ilk stay in business? What would gun writers have to write about in the next issue of every magazine? To solve this dilemma the “new caliber” ploy gets trotted out. In essence this is exactly the same way laundry detergent is sold: change a minor ingredient, tart up the box a bit, and tell everyone how much better it is than that old detergent that didn’t do anything except clean clothes.  There have been several calibers that shoot bullets 0.410” +/- (in the Metric system, 10mm). Most have been commercial failures not because they weren’t effective, but because their advertising wasn’t. It’s instructive to compare the fates of the 10mm Auto and the .41 Magnum to that of the .40 S&W. The 10mm Auto is so powerful that FBI agents had a hard time shooting it well. To address this issue the “new”.40 S&W, was brought out which very conveniently simultaneously “filled the gap” between 9mm and .45. It has succeeded not so much on its merits as because it gets great press. It won’t do anything that can’t be done with the 1905-vintage .45 ACP but that round has been around for more than a century and is, let’s face it, passé. Not exciting. Not something to shout about. Doesn’t “fill the gap.”

There have been several calibers that shoot bullets 0.410” +/- (in the Metric system, 10mm). Most have been commercial failures not because they weren’t effective, but because their advertising wasn’t. It’s instructive to compare the fates of the 10mm Auto and the .41 Magnum to that of the .40 S&W. The 10mm Auto is so powerful that FBI agents had a hard time shooting it well. To address this issue the “new”.40 S&W, was brought out which very conveniently simultaneously “filled the gap” between 9mm and .45. It has succeeded not so much on its merits as because it gets great press. It won’t do anything that can’t be done with the 1905-vintage .45 ACP but that round has been around for more than a century and is, let’s face it, passé. Not exciting. Not something to shout about. Doesn’t “fill the gap.” The beauty of the “modernity” trick is that it can be worked over and over; and—as with cartridge rifles—it can be combined with a fictitious division between “entry-level” rifles and the ones serious hunters use. If a deer can be killed cleanly with a $250 rifle, is there really any need to spend $500 or more on a “new” one? Of course not, but once the pattern of newer-is-better is fixed in the hunter’s mind, sidelock guns give way to striker-fired in-lines using #11 percussion caps; those in turn are derided as having an “obsolete ignition system” and rifles using #209 primers take their place. Then those rifles are denigrated as having “exposed” breeches, a flaw no truly “modern” rifle would have. Out come the closed-breech break-open rifles. Percussion caps and even #209 primers give way to rifles with electronic ignition systems. Loading from the muzzle? Nonsense! A modern gun uses the “

The beauty of the “modernity” trick is that it can be worked over and over; and—as with cartridge rifles—it can be combined with a fictitious division between “entry-level” rifles and the ones serious hunters use. If a deer can be killed cleanly with a $250 rifle, is there really any need to spend $500 or more on a “new” one? Of course not, but once the pattern of newer-is-better is fixed in the hunter’s mind, sidelock guns give way to striker-fired in-lines using #11 percussion caps; those in turn are derided as having an “obsolete ignition system” and rifles using #209 primers take their place. Then those rifles are denigrated as having “exposed” breeches, a flaw no truly “modern” rifle would have. Out come the closed-breech break-open rifles. Percussion caps and even #209 primers give way to rifles with electronic ignition systems. Loading from the muzzle? Nonsense! A modern gun uses the “ Over and above the designation of some species as “better” than others, there are tricks to convince hunters that how they hunt these animals is important. Right now a red-hot topic pushed in magazines is “long range” hunting, which of course necessitates rifles capable of hitting an animal at ridiculous distances. This demands that the hunter buy newer, specialized rifles and scopes, not to mention the new calibers specifically targeted (ha, ha) at people who want to shoot a deer at 600 yards or more. Can’t do that with Dad’s old Model 1894 Winchester!

Over and above the designation of some species as “better” than others, there are tricks to convince hunters that how they hunt these animals is important. Right now a red-hot topic pushed in magazines is “long range” hunting, which of course necessitates rifles capable of hitting an animal at ridiculous distances. This demands that the hunter buy newer, specialized rifles and scopes, not to mention the new calibers specifically targeted (ha, ha) at people who want to shoot a deer at 600 yards or more. Can’t do that with Dad’s old Model 1894 Winchester!  It used to be that a kid learned to hunt by tagging along with Dad, perhaps with his own .22 after a couple of years, and potted a squirrel or a rabbit now and then. When he got older he went off on his own to do it by himself. I have old advertisements from the early 20th Century showing beaming kids coming out of the woods holding dead critters they shot with their Hamilton Model 27 rifles. The kids are depicted wearing the everyday play clothes of the time: knickers, caps and neckties.

It used to be that a kid learned to hunt by tagging along with Dad, perhaps with his own .22 after a couple of years, and potted a squirrel or a rabbit now and then. When he got older he went off on his own to do it by himself. I have old advertisements from the early 20th Century showing beaming kids coming out of the woods holding dead critters they shot with their Hamilton Model 27 rifles. The kids are depicted wearing the everyday play clothes of the time: knickers, caps and neckties.