For many years a trip to Grand Canyon National park has been on Mrs Outdoorsman's “bucket list,” as has a wish to visit Arizona, the last of the 50 states she hadn’t yet seen. So on May 29th we set off to do these things. Since GCNP is within relatively close proximity to Bryce Canyon NP and Zion Canyon NP, those were added to the list.

Short version:

Fourteen days, 2026 miles on the rental car. Things Out West are very far apart, but 75- and 80 mph speed limits (and 65 mph on secondary roads) enabled us to see a lot: Four National Parks, several National Monuments, a couple of other attractions; along the way a mule ride, fourteen new bird species and a few new mammals including bison and antelope.

Long version:

We flew into Phoenix, Arizona, aboard United Airlines’ early-morning flight from Roanoke, via Chicago. Despite the early hour at which we left Chicago, the airplane was adequately staffed with screaming brats. The most prominent of these was a 3-year-old two seats behind me who went into a nuclear-melt-down-level tantrum 45 minutes into the 4-1/2 hour flight to Phoenix. I don't know how they do it, but the airlines manage to put a kid like that behind me every time I fly. I wonder if he's an employee, and when I book a ticket they give him an assignment? The horrors of coach-class (read: "cattle class") airline travel can't be exaggerated. Aside from the noise, nowadays you have to pay up front for bags (one airline is experimenting with making people pay to used the overhead storage bins for carry-ons), you have to pay for the wretched "food," which consists entirely of snacks, and there are no creature comforts like blankets or pillows even on long flights. I started traveling by air exactly 50 years before this trip, and the difference between then and now would be unbelievable to someone who's only experienced the current conditions. Luckily I have short legs, so I didn't have to pony up another $35 for an "extra comfort" seat that has enough leg room for a more normally proportioned individual.

From the air Phoenix appears as a city of one-story buildings with flat roofs, many of which sport solar panels. This makes a lot of sense, because there is a hell of a lot of solar radiation to be had free for the taking (and the cost of the solar panels). The Phoenix of mythology is a bird that rises from the ashes of the fire that destroys it: and while Phoenix AZ has not been destroyed recently, it certainly was hot enough to make me think it was going to burst into flames at any moment. The days we spent there (see below) were well above 100° and it got hotter while we were in the parks. The day before we returned the air temperature hit 116°. It reminded me of the years I spent in exile in College Station, Texas. In places like that it is literally possible to fry an egg on the sidewalk (I've seen it done) and you can get very nasty second-degree burns from a vinyl car seat.

From the air Phoenix appears as a city of one-story buildings with flat roofs, many of which sport solar panels. This makes a lot of sense, because there is a hell of a lot of solar radiation to be had free for the taking (and the cost of the solar panels). The Phoenix of mythology is a bird that rises from the ashes of the fire that destroys it: and while Phoenix AZ has not been destroyed recently, it certainly was hot enough to make me think it was going to burst into flames at any moment. The days we spent there (see below) were well above 100° and it got hotter while we were in the parks. The day before we returned the air temperature hit 116°. It reminded me of the years I spent in exile in College Station, Texas. In places like that it is literally possible to fry an egg on the sidewalk (I've seen it done) and you can get very nasty second-degree burns from a vinyl car seat.

On the ground there was far more traffic than I expected: Phoenix has about a million people when you include the outer fringe of suburbs. At certain times of day it was almost—almost but not quite—as bad as the suburbs of Washington DC.

The most visible sign that Phoenix is in a desert is the presence of saguaro cactus pretty much everywhere. These are the iconic plants with “arms,” the ones you see in Road Runner cartoons. They’re all around the airport, along the sides of streets and roads, pretty much in any open space. You would not want to parachute into Phoenix at night, because in addition to arms they have truly nasty spines. These cacti can live 100+ years and we were told they don't branch until they're about 60 years old. It was obvious that many of them had been transplanted for uses as ornamentals: they were ranged in neat lines, in orderly arrays that were obviously artificial.

The most visible sign that Phoenix is in a desert is the presence of saguaro cactus pretty much everywhere. These are the iconic plants with “arms,” the ones you see in Road Runner cartoons. They’re all around the airport, along the sides of streets and roads, pretty much in any open space. You would not want to parachute into Phoenix at night, because in addition to arms they have truly nasty spines. These cacti can live 100+ years and we were told they don't branch until they're about 60 years old. It was obvious that many of them had been transplanted for uses as ornamentals: they were ranged in neat lines, in orderly arrays that were obviously artificial.

Holes in saguaro cacti are favored nesting sites for some desert birds, especially the Golden Flicker, a species I’d never seen before. In the parking lot of our hotel I spotted some White-Winged Doves, too.

Our first visit was to “Taliesin West,” the winter home of Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright was once asked to identify himself in court and replied that he was “…the Greatest Architect In The World.” Maybe that was true or not, but whatever else he may have been, he certainly was a clever man, as well as one with an ego to match that of his good friend and fellow southwestern “artist” Georgia O’Keefe. What a team Wright and O’Keefe would have made: by comparison the Clintons would look like a shy, self-deprecating Amish couple. When she wasn’t looking through dried cow pelvises to inspire her paintings, O’Keefe would visit Wright at Taliesin West, where no doubt they would engage in mutual admiration of their respective superiority to other people.

Here’s proof of Wright’s cleverness: When The Greatest Architect in The World decided he needed a home he didn’t just build it. Oh, no: in Wisconsin he founded the first Taliesin as a “school of architecture.” What this meant was that he could have “students” come to “study” under his august tutelage, paying handsomely for the privilege of building the home of The Greatest Architect In The World to his specifications. Once the Wisconsin house was completed he decided the winters there were too harsh and that he needed a place in a warmer climate. So he founded “Taliesin West,” repeating the same scam.

Wright prided himself on using “natural materials” he found on his property, i.e., he never paid for anything when he could improvise; and the “tuition” he charged was the source of the money he used to buy what he couldn’t scrounge. The labor to build both homes—which of course was absolutely the very best way of providing invaluable and irreplaceable experiential learning for the students—was not just free, it paid a handsome profit. So he got his houses and outbuildings essentially for nothing, because so many gullible people were willing to slave in the Arizona desert for The Greatest Architect in The World.

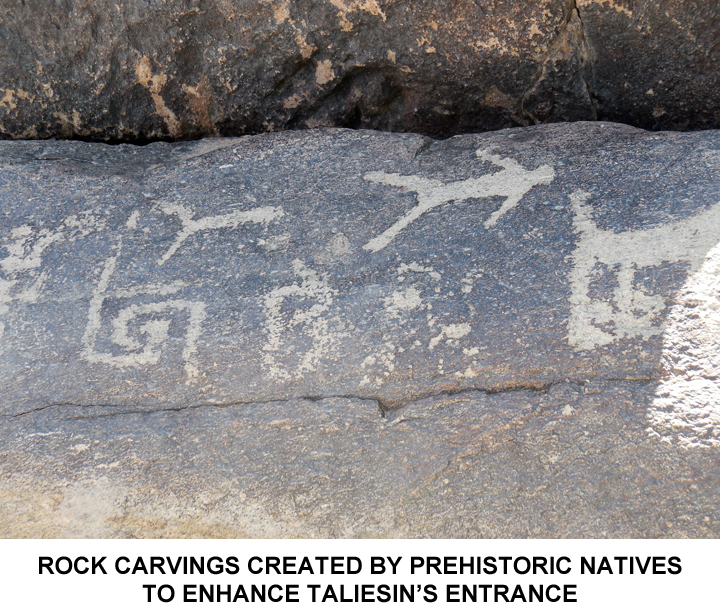

Wright seems also to have been of the opinion that laws and rules that he disliked didn't apply to him. At the entrance to Taliesin West is a nice slab of rock with pre-Columbian petroglyph carvings on it.

I asked the docent if it were in its original position, and was told that no, Mr. Wright had put it where it is now, as he felt it enhanced the look of the courtyard. Now, an ordinary person would go to jail for doing something like that, but The Greatest Architect In The World could do whatever he damned well liked with respect to Art, and to Hell with the Antiquities Act. We were also told that when power lines were strung along a highway a mile or two from the house, Wright strenuously objected to their presence as it spoiled—no, make that "desecrated"—the view. He complained, loudly and bitterly, to every official he could find, demanding that the lines be removed. When appeals to the county and the state failed, he contacted President Roosevelt! He eventually gave up, because the power lines are still there.

It is perhaps best to let The “Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture” describe itself, in this excerpt from their web site:

The Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture was formally initiated in 1932 when twenty-three apprentices came to live and learn at Taliesin… In 1931…Wright circulated a prospectus to an international group of distinguished scholars, artists, and friends, announcing their plan to form a school at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin to “Learn by Doing”....They anticipated a core faculty, “resident foremen,” at Taliesin supplemented by “a guest-system of visitation, consultation and criticism” and faculty from the “nearest university” who would make philosophy and psychology and other disciplines available “by extension work.”….The students, or “apprentices,” would [do]…“The entire work of feeding and caring for the student body so far as possible. . . work in the gardens, fields, animal husbandry, laundry, cooking, cleaning, serving should rotate among the students according to some plan that would make them all do their bit with each kind of work at some time.”…The… next year, 1932, they issued a … circular announcing the formation of the Taliesin Fellowship…organize[d] around the principles they had articulated in 1931…the program now called the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture has generally evolved along these lines….At first, Frank Lloyd Wright had few commissions through which to teach the apprentices, and he put them to work in the construction, operations and maintenance of the school. The apprentices quarried the stone and burned limestone and sifted sand from the adjacent Wisconsin River to make mortar. They cut trees and sawed them into dimensional lumber, and along with the masonry, built the large studio…that still serves as the center of learning on the Spring Green campus and as an active architectural studio. The apprentices worked on all aspects of life at Taliesin, developing a largely self-sufficient school and community that operated successfully with a very low budget….In the winter of 1935…Lloyd Wright moved the entire Fellowship to…Arizona…This inaugurated the tradition of moving the School between Wisconsin and Arizona that still continues….After the first two winters in temporary quarters, he purchased land in Scottsdale and, in 1937, with the apprentices, began the construction of a new kind of desert architecture at Taliesin West….After Frank Lloyd Wright’s death, the Senior Fellows incorporated an architectural firm to continue the practice and to mentor the apprentices.

No doubt Wright had a few chuckles from time to time as he contemplated the students engaged in experiential learning who were sweating their guts out in the Arizona desert building his winter home at minimal out of pocket cost; but Heavens, one would have to be a total Philistine to object to the pedagogical principles of such a prestigious institution. Philistines can’t appreciate true beauty. Incidentally the “Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture” is still in existence with tuition now at $40K+ per year. It is accredited by the same association that accredited my undergraduate school—so it must be legitimate, right? Right.

Some people would call Taliesin a masterful con job, but who are we to judge the motives of The Greatest Architect In The World, a man who could give lessons in how to manage real estate to Donald Trump. Such breathtaking chutzpah deserves a certain level of grudging respect.

We wanted to see Sedona, so we drove there through a very picturesque region of red rocks. In Sedona there were no saguaro cacti. The high altitude kills them, as they're frost sensitive, and we saw no more until we finally descended into the region of Phoenix again, on our return trip. There was plenty of prickly pear cactus, though, as there was everywhere we went.

The high peaks along the road leading to the city all have names, including one named "Snoopy" from its supposed resemblance to the cartoon dog asleep on his doghouse roof:

Sedona is comparatively well watered and has trees and shrubs in abundance. The town is very pretty, very chi-chi, and mostly built of what I call “pseudobe,” in which buildings actually made of poured concrete are tinted and shaped to look like adobe dwellings.

Sedona is also alleged to have special mystic significance. While it might appear to be just a dusty town in the rocky semi-desert, during the New Age “Harmonic Convergence” event of 1987, the “vortexes” that “channeled spiritual and psychic energies” were very strong there, and Sedona—not being run by dumb people—was quick to capitalize on this to become the vortex of financial and economic energies it is today. Maybe some smart hippies owned property in Sedona. (And in Sedona the plural of “vortex” isn’t “vortices”: it's “vortexes,” take it or leave it. We were specifically told this by the tourist literature. The Latin Plurals Police can lump it.)

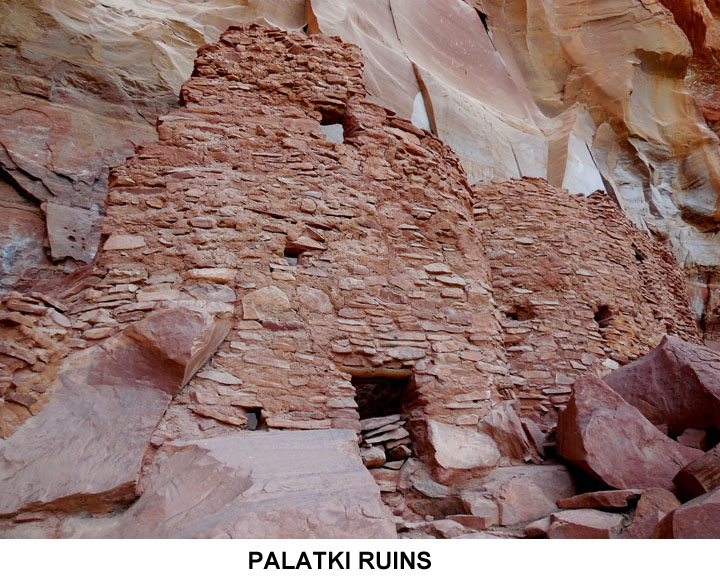

Sedona is also in an area of significant interest to students of Native American archeology. Nearby is a site with ruins of the “Palatki” tribe. I have no idea why a pre-Columbian Indian tribe had a Polish name, but that’s what they're called. We went to visit the site, clambering around on rocks, guided by a couple of elderly unpaid National Park Service volunteers. They were retirees who spend each summer in a trailer showing the ruins to tourists and watching birds. At their feeders I saw some more new birds: a Black Chinned Hummingbird, a Black-headed Grosbeak, some White-Winged Doves, and a Western Tanager.

Then it was time for The Main Event: Grand Canyon National Park. “Grand” hardly describes the place: on the South Rim (the main part of the park) anywhere you go there are spectacular views. And hordes of tourists from all over the  world. They came in busloads, thousands of them, all equipped with the one absolutely essential piece of gear needed to properly appreciate the scenery: the selfie stick.

world. They came in busloads, thousands of them, all equipped with the one absolutely essential piece of gear needed to properly appreciate the scenery: the selfie stick.

Uniform of the Day for most of the female tourists, old and young, foreign or native, was a pair of very brief jogging shorts and a sleeveless top. It’s a good thing that sunburned shoulders aren’t fatal, because otherwise the floor of the Canyon would be littered with women’s bodies. The sun was achingly bright, and I was grateful for having been smart enough to have brought along my straw cowboy hat, which Mrs. Outdoorsman had mocked. She though it looked ridiculous (I contend it was very macho) but it kept what remains of my elderly brain from being fried.

The landscape views are nothing short of eye-popping. The Canyon is 10 miles across from rim to rim, and 277 miles east to west so that “Grand” is really a wholly inadequate descriptor. The place is on a scale that’s difficult to comprehend until you see it directly. Pictures help but they don’t really do it justice. At every viewing point there would be people—usually these were foreigners—well out beyond the protective railings, sitting or standing nonchalantly over 1000-foot drops and courting death for a photo. Often these were couples embracing each other, but equally often individuals standing with their arms in the air as if they were riding a roller coaster.

I guess if you've come 12,000 miles to see the Grand canyon, you don't want the folks back home to have any doubts that you did see it; and a stupid old safety railing would spoil the picture. There is actually a book sold in the Gift Shops, Death In The Grand Canyon, cataloging every known death since God knows when, some 700+ of them. The vast majority of them were from falls off the edge. That people don’t fall in more often must be due to Divine Intervention.

Using selfie sticks while standing on an open rock precipice over a gaping hole in the ground a mile deep is a fast way to end your life, but hey, consider the ecology: buzzards have to eat too.

There were a great many foreigners, because America’s National Parks are worldwide attractions. I recognized at least 10 different languages, and there were others I didn’t. I think one couple was speaking Hebrew and another Turkish. French, German, Russian, Italian, Spanish, Arabic, Hindi, and four or five dialects of English besides American. I can’t tell Korean from Chinese or Japanese, but those countries were also well represented. We ran into a couple of elderly Dutch sisters, who had rented an RV—in Las Vegas of all places—and were spending six weeks driving to all the National Parks in the west they could manage. These two charming women looked like they were dressed for church, not stomping around dusty canyons; it was equally hard to imagine them wallowing in the fleshpots of Sin City, but they'd spent several days there before taking to the Open Road.

In the Park we stayed in little cabins, rather than the main lodge. They were comfortable enough despite having no air conditioning, because night temperatures were in the high 40’s. You can’t drive around the park (which is a good thing considering the numbers of people; nor were we there at the peak season). The National Park Service runs shuttle buses in the Canyon (and in Bryce and Zion, too). The bus service is exceptionally well organized, taking you to all the major viewpoints. I never expected that my youthful NY City experience riding crowded buses and subways would have come in handy at GCNP, but it sure did: at times the bus was as jammed as the 7th Avenue IRT in rush hour.

In the Park we stayed in little cabins, rather than the main lodge. They were comfortable enough despite having no air conditioning, because night temperatures were in the high 40’s. You can’t drive around the park (which is a good thing considering the numbers of people; nor were we there at the peak season). The National Park Service runs shuttle buses in the Canyon (and in Bryce and Zion, too). The bus service is exceptionally well organized, taking you to all the major viewpoints. I never expected that my youthful NY City experience riding crowded buses and subways would have come in handy at GCNP, but it sure did: at times the bus was as jammed as the 7th Avenue IRT in rush hour.

Entering the South Rim side we’d encountered 3 young bull elk, all in velvet. Riding the buses we saw more elk, some pronghorn antelope, a yellow-bellied marmot, ground squirrels, and more birds, including vultures and numerous ravens. There were Yellow-Eyed Juncos, Scrub Jays, and Cliff Swallows. Regrettably I didn’t get to see a California Condor, though the Canyon has them. We encountered elk and mule deer in all the parks we visited, and many pronghorns. Needless to say, they were totally habituated to humans and had no fear of them at all.

Entering the South Rim side we’d encountered 3 young bull elk, all in velvet. Riding the buses we saw more elk, some pronghorn antelope, a yellow-bellied marmot, ground squirrels, and more birds, including vultures and numerous ravens. There were Yellow-Eyed Juncos, Scrub Jays, and Cliff Swallows. Regrettably I didn’t get to see a California Condor, though the Canyon has them. We encountered elk and mule deer in all the parks we visited, and many pronghorns. Needless to say, they were totally habituated to humans and had no fear of them at all.

On our second morning in the cabins, Mrs Outdoorsman went for an early walk and encountered a rabbit and a mule deer doe calmly munching vegetation in  front of our cabin. Mule deer are everywhere in the parks, showing no

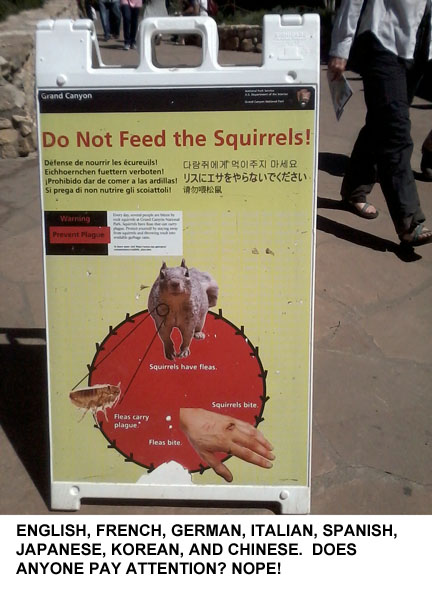

front of our cabin. Mule deer are everywhere in the parks, showing no  concern whatever about being in the proximity of people. Wildlife is of course a feature of the parks that people go to see. Now, all over the place were signs (in several languages) warning people to keep a proper distance from wildlife, lest they be bitten, stomped, or gored. Many people ignored these signs. The rock squirrels at the GCNP Lodge were especially brazen in their approaches to people, and they’ve obviously figured out that Asian tourists are a soft touch: any approach to one resulted in a giggling offer of a peanut for a photo-op.

concern whatever about being in the proximity of people. Wildlife is of course a feature of the parks that people go to see. Now, all over the place were signs (in several languages) warning people to keep a proper distance from wildlife, lest they be bitten, stomped, or gored. Many people ignored these signs. The rock squirrels at the GCNP Lodge were especially brazen in their approaches to people, and they’ve obviously figured out that Asian tourists are a soft touch: any approach to one resulted in a giggling offer of a peanut for a photo-op.

After two days on the South Rim we headed for Bryce Canyon, taking a turnoff to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon first. The North Rim is pretty isolated, nowhere near so populated as the south side, and in some respects less spectacular. On the way in we spotted a herd of bison (above) which a number of crazy tourists were approaching on foot for close-up pictures, despite the fact that there were calves in the herd. Bison may look slow and stupid and cow-like, but they can run quite fast, are very large, and would certainly trample anyone dumb enough to approach a “cute little calf.” However, there’s no reaching some people with good advice.

We were still a considerable distance from Bryce Canyon, so we spent a night in Kanab, Utah. That town bills itself as “Little Hollywood,” because so many western movies of the 40’s through the 60’s were shot there.

Kanab is very scenic but it seems to be torn between wanting to be seen as a really “western” place, while at the same time making big bucks on the tourist trade between GCNP and Bryce. There are many things about Kanab’s business district that are slightly out of place in a would-be rough-and-tumble cowboy town, including a decent Asian Fusion restaurant located half a block from an old-fashioned drugstore and next door to a big pawn shop advertising guns and western riding gear.

We drove on the next day to Bryce Canyon NP, whose geology differs from the Grand Canyon substantially. While the Grand Canyon was carved by river flow, Bryce wasn’t. In Bryce rain and the freeze-thaw cycles of the winters have created “hoodoos,” vertical pillars of multi-colored rock, rather than the sheer cliffs of the Grand Canyon. Bryce was very scenic in and of itself, and offered still more birds: American Redstarts and Western Wood Peewees, plus Oregon Juncos. There were many elk and pronghorn too. The pronghorns were utterly unfazed by cars and tourists. I’d never seen a pronghorn outside of a zoo before, and had been disappointed in not seeing any two years ago when we’d visited the Dakotas; but Bryce Canyon NP made up for the shortage.

At night Bryce is one of the darkest places in the world, much favored for star observation. We were lucky enough to arrive for the last two days of a local astronomy festival. A number of local clubs and private hobbyists had set up a field of telescopes. The sky was like nothing we’d ever seen, with tens of thousands of stars visible, not the paltry few hundred we see around here. Stumbling around the field from scope to scope in a pitch black night we were able to see Jupiter and three of its satellites (plus the colored streaks on the planet’s surface), Saturn (complete with rings and several moons), Mars, and a “globular cluster” in the constellation Hercules that was 67 MILLION light years away. There were Ranger talks on stars too: one of the Rangers was an extraordinarily gifted presenter and spoke about the life cycles of stars. I was encouraged to hear that our own Sun will probably explode, burning Earth and all the inner planets into cinders in approximately 2-3 billion years. I won’t be around for that event, I think.

Then on to Zion Canyon NP, a place of sheer rock walls and the Virgin River. Also 100°+ heat in the daytime! There we did a few short and gentle hikes. One was to a place called the “Weeping Rock.” This is the exit from an aquifer whose outflow allegedly takes 1200 years to find its way through. I have no idea how this time frame could be verified but I’m no geologist. What they tell me I have to believe. There was more wildlife in Zion: mule deer (one in the bushes next to our hotel), plus an Orange Crowned Warbler and a Spotted Towhee or two.

One of the high points in Zion—and of the entire trip—was a trail ride on mules. You can do these in the Grand Canyon and Bryce, too, but those  rides were too long for our taste. I’d not been on any sort of equine for nearly half a century but I’d been told by someone who had reason to know that mules are easier to ride than horses, so I specifically requested a mule. My mount was named “Barbara,” a sweet old thing who politely refused to throw me off. Mrs Outdoorsman was riding “Fancy.” On our way out of Zion NP to the next phase of the trip, Mrs Outdoorsman spotted a bighorn sheep, but I missed it.

rides were too long for our taste. I’d not been on any sort of equine for nearly half a century but I’d been told by someone who had reason to know that mules are easier to ride than horses, so I specifically requested a mule. My mount was named “Barbara,” a sweet old thing who politely refused to throw me off. Mrs Outdoorsman was riding “Fancy.” On our way out of Zion NP to the next phase of the trip, Mrs Outdoorsman spotted a bighorn sheep, but I missed it.

I wanted to go to the Four Corners National Monument. That’s the geographical point where Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona meet. To do this we had to drive across the width of the Navajo reservation, which was fine with me. Both of us had long ago read all of Tony Hillerman’s crime novels set in the Navajo country with a detective with the Navajo Tribal Police as the protagonist. I wanted to see the country Hillerman wrote about. We stopped for lunch at a very unpretentious eatery called “The Blue Coffee Pot” in Kayenta, about halfway to Four Corners.

The Blue Coffee Pot is likely the social center of Kayenta (population 5100). It’s an octagonal building, reflecting the most common shape of the hogan, traditionally a Navajo home but nowadays used mainly for ceremonial purposes. Nonetheless the hogan occupies a central place in Navajo culture even today. We were just about the only belaganas (non-Native Americans) there. I had been looking for a place with some authenticity and Navajo cooking, and this was as close as I got: they were serving mutton wraps. I like mutton and had hoped to find some traditional mutton stew (with fry bread) but The Blue Coffee Pot only serves that on Thursdays, and it was Wednesday. Oh, well, I did get some mutton, a staple of Navajo cooking since the Spanish brought sheep in the 16th Century.

The Blue Coffee Pot is likely the social center of Kayenta (population 5100). It’s an octagonal building, reflecting the most common shape of the hogan, traditionally a Navajo home but nowadays used mainly for ceremonial purposes. Nonetheless the hogan occupies a central place in Navajo culture even today. We were just about the only belaganas (non-Native Americans) there. I had been looking for a place with some authenticity and Navajo cooking, and this was as close as I got: they were serving mutton wraps. I like mutton and had hoped to find some traditional mutton stew (with fry bread) but The Blue Coffee Pot only serves that on Thursdays, and it was Wednesday. Oh, well, I did get some mutton, a staple of Navajo cooking since the Spanish brought sheep in the 16th Century.

We made a stop at the Navajo Nation Memorial. This site includes well-preserved ruins of a 12th-Century pueblo in a colossal cave, that regrettably can only be seen from a distance. There were many exhibits along the paths to the overlook, discussing Navajo culture and history. Having done this we pressed on to the Four Corners National Monument, which is also on the reservation.

Despite its isolation at the far northeastern corner of Arizona the Four Corners is a very popular tourist site. When we arrived several tour buses were disgorging passengers and like everyone else we stood in line to have our pictures taken in “four states at once.”

You do this by kneeling down, with the left hand in one state, the right in a second, and each foot in the third and fourth respectively. Everyone was doing that. I found it easy to get down on all fours but at my age getting up again and returning my elderly carcass to a vertical condition within a single state was a lot more difficult than getting down. I think I arose in Arizona but it might have been New Mexico where I finally managed to stand up.

Back across the reservation for a brief night in Flagstaff (that was a long day: 12 hours’ time on back roads) and a couple of stops there. The first place we saw was The Meteor Crater, the site of a gigantic (privately owned) hole. The hole is the remnant of an impact by a school-bus-sized chunk of some former planet that hit Earth millions of years ago. The impact blew a hole a mile across and originally a thousand feet deep. Drifting dust has filled in some hundreds of feet at the bottom, but it’s still well over 500 feet down from the rim. Very impressive. We were told that NASA had used the Crater as a testing ground for space suits prior to the Apollo missions to the Moon. I can well believe it.

We left the Crater and passed through the Petrified Forest National Park, the fourth NP on this trip (not counting National Monuments). Part of this NP is the “Painted Desert,” which to be honest looked much like any other parts of the desert, though a little pinker than some areas. It wasn’t any more “painted” than the various canyons, all of which featured lots and lots of pink rocks. The southern end of this NP took us through the Petrified Forest. Millions of years ago some trees fell down and were turned into stone but nobody made clear how this happens. In that park I yet saw another new bird, a Red-Backed Junco. We then headed for Phoenix via back roads through the Tonto National Forest, a very scenic route that took us up over 9000 feet elevation through a heavily pine-wooded region towards Flagstaff.

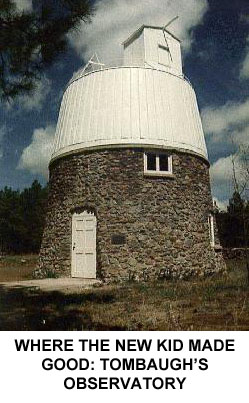

Flagstaff is the site of the Lowell Observatory. It was there that one Clyde Tombaugh, a farm boy from Kansas who badly wanted to become an astronomer, got a job as what amounted to a janitor. Tombaugh was assigned the title of “Assistant Observer,” and allowed to look for what was then called “Planet X” when he wasn’t mopping floors and running errands  for the Brass. Percival Lowell, the founder of the observatory, had predicted the presence of a planet beyond Neptune based on mathematics and the New Kid was told he could look for it so long as he didn’t neglect his other duties. So, after a few months of scut work by day and freezing his butt off at night looking for Planet X, he “made good.” The planet was pretty much where Lowell (by then deceased) had said it would be, and Tombaugh spotted it by a laborious process of comparing hundreds (perhaps thousands) of photographic plates. "Planet X" was eventually re-named Pluto.

for the Brass. Percival Lowell, the founder of the observatory, had predicted the presence of a planet beyond Neptune based on mathematics and the New Kid was told he could look for it so long as he didn’t neglect his other duties. So, after a few months of scut work by day and freezing his butt off at night looking for Planet X, he “made good.” The planet was pretty much where Lowell (by then deceased) had said it would be, and Tombaugh spotted it by a laborious process of comparing hundreds (perhaps thousands) of photographic plates. "Planet X" was eventually re-named Pluto.

Tombaugh was immediately promoted to “Observer,” (he still didn’t have a college education), and received offers from many universities to come and study there. It’s not every day that someone discovers a new planet, after all. He accepted the offer from the University of Kansas, and eventually returned to Lowell as a full-fledged Astronomer.

Pluto has since been demoted to “dwarf planet” status, and perhaps it’s a good thing that neither Lowell nor Tombaugh are around to witness Pluto’s humiliation. We also had a chance to look through a heavily-filtered telescope at the sun: the filters allowed us to see a sunspot (that was bigger than the entire earth, though it appeared as a mere flyspeck on the surface of the sun) and “filaments” of sun gasses where the surface is fissured. And yet another new mammal: on the grounds of the Observatory I saw my first Abert Squirrel, the kind with heavily tasseled ears.

Eventually we reached Phoenix, arriving in the middle of the Friday evening rush hour, when the traffic was even worse than it had been on arrival. The temperature had moderated from the peak of 116° to a mere 100-102° when we got there. That Saturday, our last day of touring, we hit two of Phoenix’s major museums. These were the Heard Museum, specializing in Native American Arts and—another major high point of the trip—the Musical Instrument Museum.

The Heard’s collection was interesting enough even though I know even less about Native American art than most other kinds. They did have an interesting exhibit on the “boarding schools” where Indian children were forcibly compelled to “assimilate” by being denied the right to speak in their native languages and to adopt “western” clothing and habits. Boarding schools still exist on the reservations but they’re now attended voluntarily rather than under compulsion.

The Musical Instrument Museum was nothing short of phenomenal. I was expecting a smallish old building with a few rooms, but the place is an enormous modern construction. The exhibits are grouped by continents and countries (and in the North American section, by genre). There aren’t the usual wordy signs. Instead the visitor is issued a head set and each exhibit has a small video screen. As you walk up to an exhibit video clips play, showing some or all of the instruments on display in use. The signage is limited to telling you what music is being played. As you walk around, you catch snatches of music here and there. It’s an amazingly effective technique that gets the point of the museum—music and how it’s made—across better than anything else could. As to the instruments themselves, there are tens of thousands of them. Many of the instruments are wildly unfamiliar to western audiences, and not a few of them represent ingenious adaptations of locally-available materials. One “guitar” was made from a 5-gallon Castrol oil can; others were made from cigar boxes and armadillo shells. The point is that music is universal, that people must make music, and that they will do so even if all they have at their disposal is a mountain of trash or a few sticks and reeds. In one exhibit highlighting “Music In the Home” in the 19th and early 20th Centuries, there was on display a Columbia “Graphophone,” an early record player for wax cylinders. It’s identical to the one I own! Regrettably we didn’t get to the Museum until the afternoon of our last day, and were unable to visit all the exhibits: three hours there wasn’t nearly enough time. The “MIM” is one of the most interesting and fascinating places I’ve ever visited and will be a must stop if we return to the West.

A couple of years ago we’d visited Theodore Roosevelt NP in North Dakota. At the time we’d purchased a “Senior Park Pass” that is good for life and cost only $10. That got us into all the “fee” sites the Park Service and Forest Service operate. Since the fee for entry into the parks is $30 per car it saved us a lot of money! I mentioned the bus service, but I’ll close by adding that the NPS contractors that run the lodges and their associated restaurants also do a great job. The food was in general very good, service was attentive and prompt, and given that leaving the Parks for a meal was usually a PITA, we appreciated that. The Visitor centers at every attraction were informative, well laid out, and efficient, given the size of the crowds. It seemed at times that every building at every stop included at least one Gift Shop, so there was no lack of opportunity to buy junk.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |