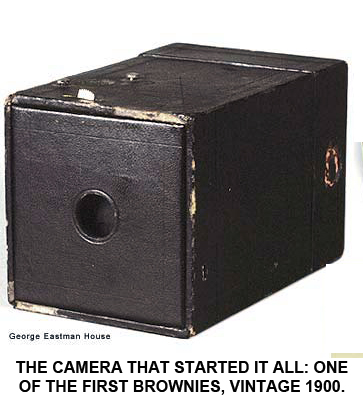

George Eastman is one of history’s great pioneers. He didn’t invent the camera (most authorities credit Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and W.H. Fox-Talbot for that accomplishment) but he did “invent” the notion of lightweight, portable, easily used cameras that appealed to the general public, especially those who wanted mementoes of their travel, family gatherings, celebrations, and general life without having to visit a professional photography studio. Prior to Eastman’s introduction of cameras specifically for the consumer market, photographic equipment was heavy, cumbersome, and incredibly difficult to use: Matthew Brady, for example, who made thousands of images of Civil War battlefields and the famous people of his day, used cameras weighing hundreds of pounds, and for his work he needed a horse-drawn “traveling darkroom” to prepare his wet glass plate negatives and develop them. Photography was a profession, not a hobby, but Eastman changed all that with the introduction of the original “Brownie” box camera in 1900. It created a revolution and spawned an industry. “Kodak” was the name he gave to his product (he wanted a name that was “...short, easy to pronounce, and not associated with anything else.” So pervasive was the impact of his company and its inventions that in time the word "Kodak" became synonymous with any camera at all. (The name “Brownie” was a tribute both to its designer, Eastman’s employee Frank A. Brownell; and to the old comic strip characters, “The Brownies.”)

George Eastman is one of history’s great pioneers. He didn’t invent the camera (most authorities credit Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and W.H. Fox-Talbot for that accomplishment) but he did “invent” the notion of lightweight, portable, easily used cameras that appealed to the general public, especially those who wanted mementoes of their travel, family gatherings, celebrations, and general life without having to visit a professional photography studio. Prior to Eastman’s introduction of cameras specifically for the consumer market, photographic equipment was heavy, cumbersome, and incredibly difficult to use: Matthew Brady, for example, who made thousands of images of Civil War battlefields and the famous people of his day, used cameras weighing hundreds of pounds, and for his work he needed a horse-drawn “traveling darkroom” to prepare his wet glass plate negatives and develop them. Photography was a profession, not a hobby, but Eastman changed all that with the introduction of the original “Brownie” box camera in 1900. It created a revolution and spawned an industry. “Kodak” was the name he gave to his product (he wanted a name that was “...short, easy to pronounce, and not associated with anything else.” So pervasive was the impact of his company and its inventions that in time the word "Kodak" became synonymous with any camera at all. (The name “Brownie” was a tribute both to its designer, Eastman’s employee Frank A. Brownell; and to the old comic strip characters, “The Brownies.”)

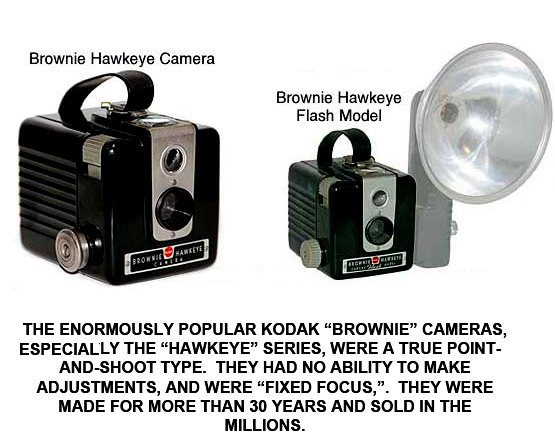

Brownie cameras were what today would be called a “point and shoot” type. Most of them lacked any sort of sophisticated adjustment capability for focus, exposure, etc., but they were enormously successful precisely because they were simple enough for anyone to use. But things change with time and today the “point-and-shoot” non-adjustable camera is dead; “point and shoot” cameras today are pretty sophisticated, auto-focusing ones which also compensate for exposure pretty much under any conditions.

Brownie cameras were what today would be called a “point and shoot” type. Most of them lacked any sort of sophisticated adjustment capability for focus, exposure, etc., but they were enormously successful precisely because they were simple enough for anyone to use. But things change with time and today the “point-and-shoot” non-adjustable camera is dead; “point and shoot” cameras today are pretty sophisticated, auto-focusing ones which also compensate for exposure pretty much under any conditions.

Even the electronic-based, digital point-and-shoot camera has likely received a mortal wound from the smart phone. Read a review of any smart phone and you’ll find at most a single paragraph about how it deals with the phone’s original purpose of telephonic voice transmission. The quality of the phone’s browser will get a lot more space: what gets the most verbiage (and pictures) is the quality, or lack thereof, of the built in cameras. Yes, “cameras” plural: including one that allows the owner to indulge in the abominable self-adorational pictures that infest the world: “selfies”. The other, the main camera, is for doing just what the point-and-shoot used to do: taking pictures without having to fiddle overmuch with f-stops, aperture settings, and ISO adjustments. The smart phone has relegated even the digital point-and-shoot camera to the realm of VHS, eight-tracks, and cassette tapes.

Cameras now (and for the near future, anyway) fall into one of three categories: digital single-lens reflex (DSLR), travel cameras, and water-resistant pocket cameras. I still have a high quality SLR, single lens reflex, camera and it would no doubt perform its function as well as it ever did; if I could get film, and if I could get the film developed. For most purposes we can just drop the “D” off DSLR because all but the most specialized cameras today are digital and film has gone the way of coal oil lamps and high button shoes.

DSLR’s are amazing cameras, most of them capable of using interchangeable lenses and various accessories that are pretty much relegated to specialized situations outside the scope of this article. If you want to have the chance of getting really professional-quality pictures, you’ll need to put up with the weight, cost, and learning curve of a DSLR system. But if you're just wanting decent images of your trip, be it hunting, fishing, or just sightseeing, you’ll want either a travel or water-resistant camera.

Today's travel camera, such as the one above, can do the majority of what most people want done. They’re compact, lightweight, and provide excellent images as long as they won’t be magnified beyond about 8 x 10- inch prints. A good one will fit in a jacket pocket or a baggy shirt, have enough settings and adjustments to overwhelm the majority of users, and have a zoom lens more powerful than the 35 mm film cameras could even dream of. When point-and-shoot cameras first emerged, the race among the manufacturers was to see whose could produce the most detailed pictures.

Today's travel camera, such as the one above, can do the majority of what most people want done. They’re compact, lightweight, and provide excellent images as long as they won’t be magnified beyond about 8 x 10- inch prints. A good one will fit in a jacket pocket or a baggy shirt, have enough settings and adjustments to overwhelm the majority of users, and have a zoom lens more powerful than the 35 mm film cameras could even dream of. When point-and-shoot cameras first emerged, the race among the manufacturers was to see whose could produce the most detailed pictures.

As mentioned, film is deader than Disco, for a variety of reasons, including convenience, low cost (no need to spend money on developing) and immediate feedback on the image taken. The thing inside a digital camera that takes the place of film is a “Charged Coupling Device” (CCD) and the detail in a picture is a function of how many "pixels" (picture elements) the makers can cram onto a CCD while keeping the CCD small enough that the camera containing it would still fit in a pocket. Most CCDs (aside from SLRs) are in the range of a third of an inch square, and even with the best of modern technology, the pixels that record the value of light striking it get too crowded on that small an area to record a quality image after you cram in more than 10 to 15 megapixels. That’s 10 to 15 million pixels crammed into an area smaller than your little fingernail, so it’s no wonder that the pixels interfere with each other in any other than perfect lighting conditions. The interference is called noise. The competition on that front has been won; the manufacturers trying to sell you on the idea of 18, 20, and 22 megapixels are continuing to run after the finish line has been crossed and they’re counting on your ignorance to think even more is better. For adjustments on this type of camera, a lot of them are “gee-whizz” settings that never get used. Seriously, are you going to want to take a picture of your daughter with her first deer when all the colors are deliberately shifted to a neon effect?

While each trip might slightly affect which camera setting you use most, there are a few that are quite handy in many cases. One of the great advantages of any digital camera is that you can look at a picture you’ve just taken to see if it is blurry, or the composition is off. This is something you could never do with a film camera. But you might not want to view the picture immediately after you’ve taken it; while it is on your screen awaiting your admiration, another opportunity for a great picture might be lost. So a travel camera should have an internal setting allowing you to reduce or eliminate the review time. After the action you’re photographing is done, you can always go back and sort out the good shots from the others.

While each trip might slightly affect which camera setting you use most, there are a few that are quite handy in many cases. One of the great advantages of any digital camera is that you can look at a picture you’ve just taken to see if it is blurry, or the composition is off. This is something you could never do with a film camera. But you might not want to view the picture immediately after you’ve taken it; while it is on your screen awaiting your admiration, another opportunity for a great picture might be lost. So a travel camera should have an internal setting allowing you to reduce or eliminate the review time. After the action you’re photographing is done, you can always go back and sort out the good shots from the others.

While considering the frequent need for several rapid-fire exposures to capture action, there should be a setting for “bursts” of pictures; the camera acts like an automatic and keeps taking pictures as long as you hold down the shutter release. Do you think your son, fighting his first salmon, is going to be able to hold still for you to set up a picture, or the fish will cease flopping for it? The timing on the burst setting is often adjustable so that you can shoot at 3, 6, 10 and more frames per second. And of course it should have the normal settings for self-timed pictures, settings to let you accelerate the shutter speed or increase the depth of field, one that will disable the flash or activate it for fill-in light, and the various settings we’ve come to expect on any camera.

What differentiates the travel camera from its point-and-shoot predecessor, however is the zoom Typical point-and-shoot cameras have optical zooms of 4 or 5 power. A shot taken at 10 yards would be zoomed in as if it was 4 or 5 yards; this is very handy when taking a picture of the rattler that you found in camp. To get any more power out of the zoom, point-and-shoot cameras indulged in electronic chicanery, using digital wizardry to focus in on just those pixels that contained the subject you wanted. But as it concentrated on only those pixels, the detail that the other pixels would record using optical zoom was lost. A travel camera’s optical zoom capability will give you 20, 30, and more power magnification and the quality of the resulting picture is limited only by the quality of the lens. However, when magnifying a subject 20 times, it also magnifies the hand-held shake of the camera, so getting a clear super zoom picture requires a bit of additional bracing, if not a tripod.

What a travel camera generally doesn’t have is the ability to resist the rain or worse, a dunking; and limited ability to deal with dust. To achieve the zoom effects of a travel camera, the lens must extend out from the body to get the necessary focal length required. Those sections of lens that roll out and roll back in for the zoom lens allow water and dust to get inside the camera, and the various ports and slots that allow you to hook up the camera to a computer or change the battery will readily let in the water and immediately destroy your camera, as for example when it sits on the bottom of the boat and a bit of water sloshes in. Those are the conditions when you have to decide what you want most. You can use a plastic bag or watertight container to keep the camera from being ruined, but that will eliminate your ability to take any of those spur-of-the-moment pictures that arise on any trip. Or, you can get a water-resistant (often truly waterproof if you don’t take it too deep) camera.

The settings on a water resistant camera are similar to those on a travel camera, but often include one or more that allows you to deal with the color shift that occurs in underwater situations, as when you’re snorkeling. Too, if the camera will keep out water with thoroughly gasketed ports and slots, it will also keep out dust and pocket lint. Its drawback hearkens back to the original point-and-shoot cameras: there’s no lens extrusions to allow high zoom settings; you are restricted to the 4 or 5 power zoom of the originals. You have to decide whether you want the ability to capture images of far away things or whether you’re satisfied with closer things on regular basis; regardless of rain, dust, and the generally crappy weather that we often play in while calling it fun. And, to wash off the moose blood after you’ve recorded your fun for posterity, simply wash it in the sink.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |