I was born in a now long-gone small private hospital on West 183rd Street in the Bronx; my father was a physician on their staff. At that time (1947) he was living in and practicing in a house in the northwest corner of the Bronx, at 3117 Kingsbridge Avenue. He had bought that house in late 1946 and raised me and my four siblings in it; he earned his living in it, and eventually he sold it, and his practice, to another doctor. That was in the early 1980's.

If you look this address up on various real estate databases it will give a construction date of "1901," but this is absolutely wrong. Irked by this persistent error, I did some digging into the history of the building and its owners, along the way uncovering some very interesting information about it, about the neighborhood, and about the people who lived there before my family did.

My house—I can think of it in no other terms, even now—was in fact built about 1888, give or take a year. The "1901" error seems to have arisen thanks to the creation of the Borough of the Bronx as part of the Greater New York Act, which went into effect in 1899. Before that date The Bronx as a "Borough" didn't exist at all, but the house did.

My neighborhood, Kingsbridge, existed long, long before that time, and has an interesting history of its own. At one time it was part of Westchester County, a town in its own right dating to the late 17th Century. In 1874, the part of Westchester County in which it was located became part of New York City as what was referred to as "The Annexed Section"; in other words the city took over pretty much all the land west of the Bronx River, including the Town of Kingsbridge.

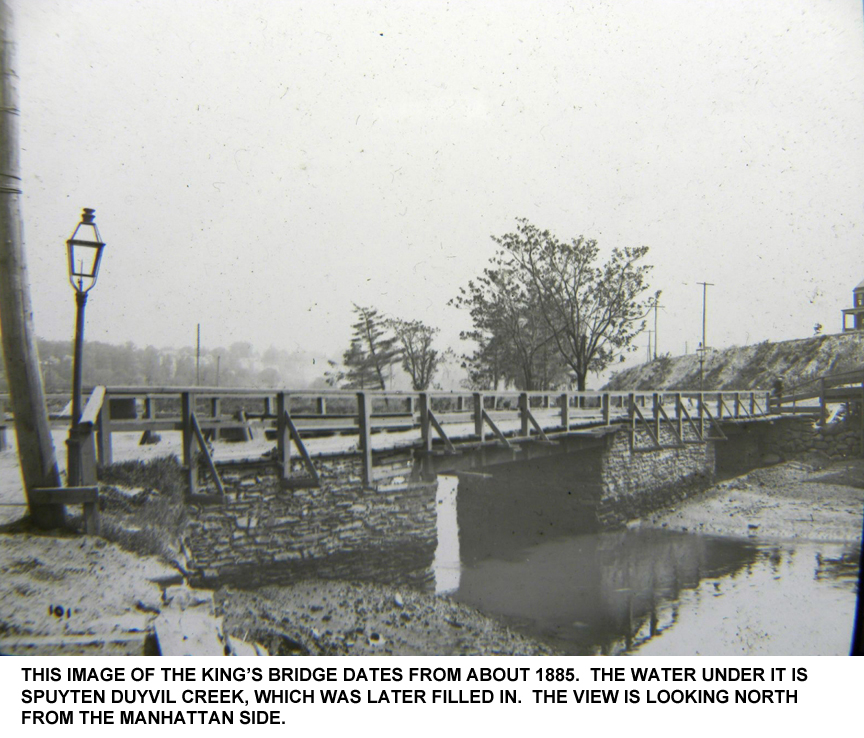

The Town of Kingsbridge, which existed long before the Revolutionary War, took its name from "The King's Bridge," a structure spanning the then-extant Spuyten Duyvil Creek. The King's Bridge was built some time in the 17th Century and for many years was the only way to cross dry-shod from Manhattan Island to the mainland.

In his retreat after losing the Battle Of Brooklyn, George Washington took his troops across it, and it seems likely they made camp pretty much on the spot where my home was later to be built, as it is not very far away from the place where the King's Bridge crossed Spuyten Duyvil Creek—a matter of one and one half city blocks today.

Spuyten Duyvil Creek was filled in more than a century ago, but the location of the original King's Bridge is known: it was on the south side of what is today the intersection of West 230th Street and Kingsbridge Avenue. The Creek was the political boundary between the Bronx and Manhattan and where the bridge used to be still is today: the equally-old neighborhoods of Spuyten Duyvil and Marble Hill south of 230th Street, are legally part of the Borough of Manhattan, not part of the Bronx at all. Once you cross to the south side of 230th Street, what was "Kingsbridge Avenue" in the Bronx becomes "Marble Hill Avenue" in Manhattan. Such are the vagaries of politics and map-making.

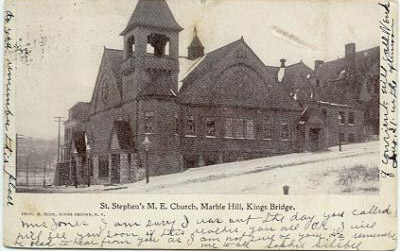

As an aside, my Boy Scout troop held its weekly meetings in the basement of St Stephen's Methodist Church, pretty much the first building on Marble Hill Avenue. Although according to the Boy Scouts of America we were in "Troop 59, Bronx," in fact we met in Manhattan! The image at left shows St Stephen's some time in the early 20th Century. The view is from the 230th Street side, looking south. The photographer is in the Bronx; the Church is in Manhattan, but it's no longer on "Kingsbridge" Avenue. At that point it's Marble Hill Avenue!

In 1874 New York City annexed the area west of the Bronx River. This was initially called the "annexed district," but despite being technically within New York City's boundary Kingsbridge remained a pretty isolated and more or less rural area until the early 20th Century when things changed greatly and relatively rapidly.

In 1874 New York City annexed the area west of the Bronx River. This was initially called the "annexed district," but despite being technically within New York City's boundary Kingsbridge remained a pretty isolated and more or less rural area until the early 20th Century when things changed greatly and relatively rapidly.

The Interborough Rapid Transit Company, New York's earliest subway system, opened its first lines in 1904; by 1908 the IRT had extended its lines via an elevated section as far north as 242nd Street, which is still the final terminus. Once that line was completed residents of Kingsbridge could easily reach the business districts of central and lower Manhattan; a residential explosion took place as a result.

By 1919 the apartment houses had begun to go up on Kingsbridge Avenue and the transition to a densely-settled urban region was well underway. No more a small and quiet corner of the city, Kingsbridge became a bit of a boom town, thanks to the subway.

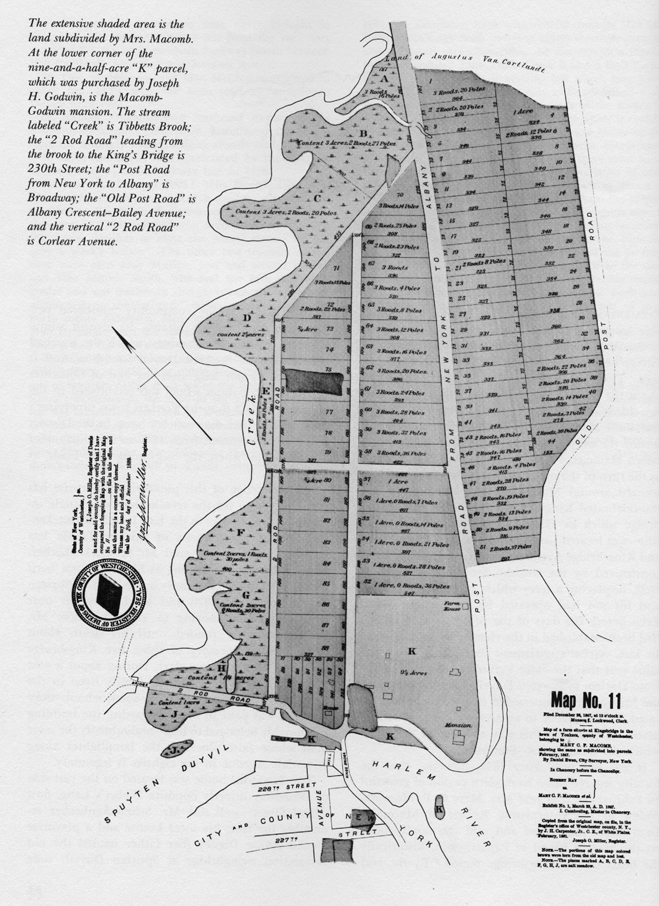

The map above is a surveyor's plat of the area in about 1889, delineating the subdivision of a large property owned by the Macomb family. Note that south of the point where the King's Bridge crosses Spuyten Duyvil Creek and the Harlem River, the map shows the "City and County of New York," i.e., Manhattan; this despite the fact that by 1889 Kingsbridge and the entire "annexed district" were legally in the City (but not New York County).

The "creek" at the left boundary of the Macomb property is Tibbett's Brook. This brook was long ago covered over, although it still flows, completely unseen, beneath the surface and drains into the city sewer system. The "Post Road" on this plat is now Broadway; the cross street shown intersecting the "Post Road" is now West 232nd Street.

As I mentioned, my house was built some time in the mid-1880's. On maps published by the G.W. Bromley Company its history and timeline can be traced fairly closely. On Bromley's maps, structures made of brick are shown in red; wood frame buildings in yellow.

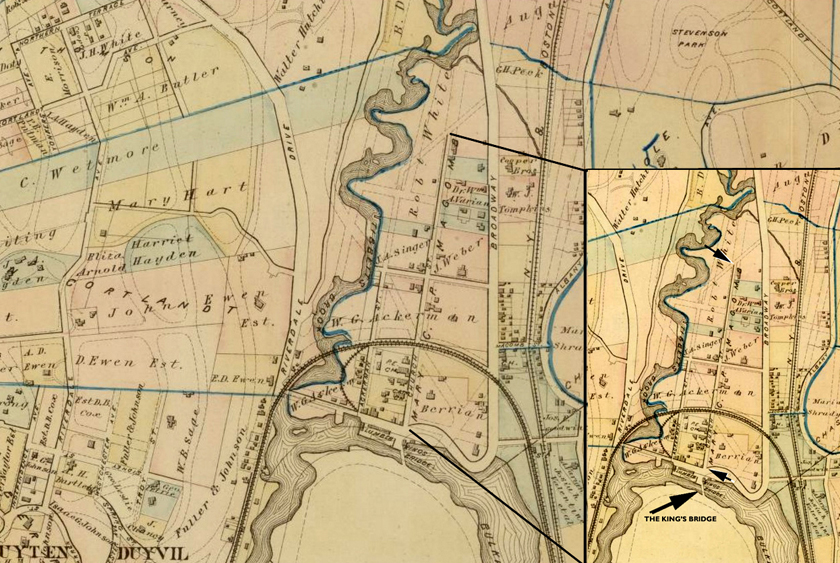

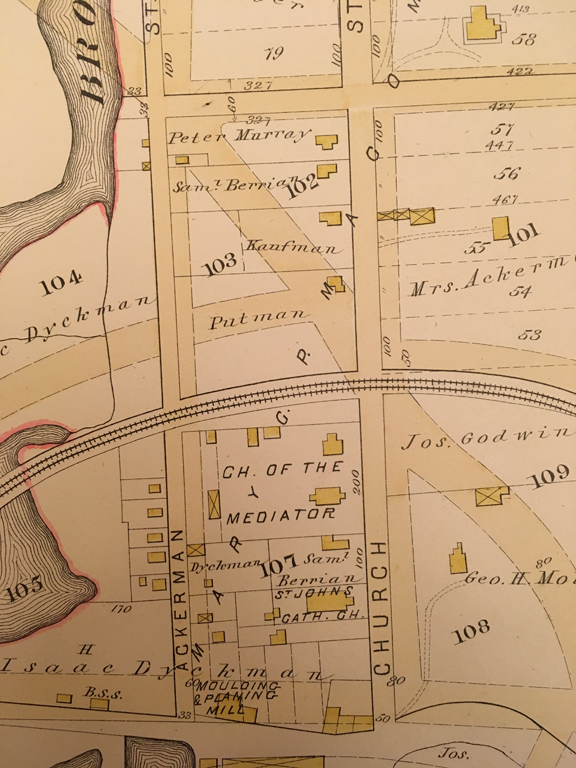

The Bromley maps for 1879 and 1882 don't show the house at all. The map above is from 1879. The inset shows the name "Mary Macomb" on the east side of what is labeled "Church Street." By 1879 a railroad line had been constructed that looped through Kingsbridge at the level where West 231st Street was eventually to be built. "W.G. Ackerman" is shown as the owner of the western side of Church Street.

If you examine the 1882 map (above) what today is called "Kingsbridge Avenue" was "Church Street." I'm not entirely certain when the name was changed, but probably it was around the time of annexation, although Bromley used the original name on this map.

"Church Street" was an apt name. There were (and still are are) two large churches on it, just below the railroad line. One is the Roman Catholic St John's, whose parish was first established in 1877 in a wood frame building; the current Gothic-style church was built in 1904. Older and more established is the Episcopal Church of The Mediator just to the north of St John's. That parish dates to 1855. It too was first housed in a frame building that later was replaced by a magnificent stone one. Both pre-dated annexation, so even if the name was changed in 1874-75, "Church Street" would have been what the residents called it. On the 1882 map The Church of The Mediator is at the corner of Church Street and what later came to be 231st Street; that's shown as a place where the railroad makes a large loop to the west.

By 1882 the block on Church Street where eventually my house would be constructed, belonged to someone named "Kaufman." A wood framed house is shown on this spot on the 1882 map. That house was still in place when I was very small; I remember it as an abandoned property, later torn down. That lot and the adjacent properties to the north eventually became the location of a convent and "St John's Academy," a parochial school run by St John's Church. Today there's still a St John's school on that spot: I well remember its construction in 1953.

In 1882 231st Street didn't yet extend west of Broadway. That part of the Bronx is very rocky and the west side of Broadway was a solid granite hill. Much later (probably no earlier than 1907) the railroad line was re-routed and 231st Street was extended westward to what is now Riverdale Avenue. This certainly required not only picks and shovels, but dynamite in prodigious quantities. Today Ewen Park, located at the foot of West 231st Street, is a very steep incline with massive outcroppings of the local stone.

It's probable that given the labor required to do it, West 231st Street wasn't completed until 1909-10; a 1904 map still shows the railroad line where it was eventually to go. And Church Street was carried over the railroad line via a small bridge crossing a deep cut for the tracks.

By 1888, the Bromley map (above) shows a brick structure on Block 102, with a frame structure behind it. Note that the brick building is not divided into two parts, which indicates to me that it was still under construction. And the map's name of Church Street has been changed to "Kingsbridge Avenue." That brick structure was what later became my house. Kingsbridge Avenue was still routed over the railroad line via a bridge because 231st Street had not yet been extended.

The Bromley map of 1893 is very informative. It still shows a brick structure on Block 102, but this is now clearly divided into two parts: #95 and #93 to its north side. That is, it's one building with a property line running through it. It was in fact a "duplex." That was my house.

Note also that on the 1893 map, there's a frame structure behind the southern part of that duplex. It was a stable that was still there when I was a boy, and further serves to identify the property as unquestionably the house in which we lived.  When I was small there was an enormous American Elm tree in the corner next to the stable. When I was about 10 years old my father hung an old tire in the tree to serve as a swing. By the early 1970's, thanks to the ravages of Dutch Elm Disease, the elm tree had died and had been cut down. As the massive stump rotted away, there was revealed...an iron gatepost! It had been the gatepost for the stable yard; as the elm planted in the 1880's grew, it engulfed the post and hid it for nearly a century.

When I was small there was an enormous American Elm tree in the corner next to the stable. When I was about 10 years old my father hung an old tire in the tree to serve as a swing. By the early 1970's, thanks to the ravages of Dutch Elm Disease, the elm tree had died and had been cut down. As the massive stump rotted away, there was revealed...an iron gatepost! It had been the gatepost for the stable yard; as the elm planted in the 1880's grew, it engulfed the post and hid it for nearly a century.

There was a stable because various owners before my father kept a horse and carriage, and in my pre-teen years I more than once climbed into the hayloft of that stable (which, by the way, I was strictly forbidden to do) and found therein the account books of the man who tended the horse, as well as his receipts for purchases of hay. On the back wall of the stable was a window covered by a tin sign advertising the soft drink "Moxie." Somewhat inexplicably this sign featured a man on a horse next to a Stutz Bearcat automobile.

By 1904, the Borough of the Bronx had been in existence as such for about 5 years; the Block number had been changed to 3403. Kingsbridge Avenue was the official street name but the old name of "Church Street" was still shown on the maps! The divided brick building is labeled "#93" to the north and "#95" to the south. Whether these are actual addresses or simply lot numbers I don't know.

We lived in what in 1904 may have been "#95 Kingsbridge Avenue"; but the official address was later changed, probably after the completion of the western extension of 231st Street. On the 1893 map, the street just north of my house is labeled "Weber's Lane," but this later was re-designated "West 232nd Street." The re-numbering of houses to coincide with cross streets must have come once 231st Street was finished. Examination of the 1905 New York State Census shows the street as Kingsbridge Avenue. So the address that might have once been "95 Kingsbridge Avenue" would have been re-designated as "3117 Kingsbridge Avenue," based on the closest cross street being West 231st. Buildings north of what was "Weber's Lane" in 1893 would have had addresses that began with"32" once the name change to West 232nd Street was made.

We lived in 3117; the other side of the building was 3121 Kingsbridge Avenue: these correspond to #95 and #93 on the 1904 map. 3121 Kingsbridge Avenue belonged at one point to my grandfather and later to one of my uncles: My father ran his medical office in 3117, my two dentist uncles practiced in 3121. I never actually made any distinction in my mind between the two sides with respect to ownership, nor did anyone else in my family: so far as we were concerned it was all one house.

Not only Kingsbridge Avenue's name has changed over the decades: so has its basic geography and topography. About the same time that West 231st Street was completed (roughly 1907) Kingsbridge Avenue was re-graded from its original level and paved.

The image above is from 1907. The street is being lowered from its original level, trees have been removed, and it's being prepared for paving. The railroad cut has been filled in but the small bridge that carried Church Street over the railroad is still present. This view is looking north along Kingsbridge Avenue with what will soon be West 231st Street crossing the image from right to left. It will obliterate the remains of the small bridge. In the middle of the picture is a house with two chimneys: that's my house.

In 1909, a school was constructed at the intersection of Kingsbridge Avenue and "Weber's Lane," by then West 232nd Street. This was Public School No. 7, or "PS 7" as it was universally called. I went to kindergarten there in 1952, and the building looked exactly as it did in 1909. It's shown below in what is probably the earliest picture of it.

Kingsbridge Avenue is running from left to right in the foreground: West 232nd Street crosses it right to left. Neither street has been lowered yet. The cupola at the top of the building collapsed in the early 1960's and my brother told me he watched this happen. The rest of the building was eventually torn down and replaced with a newer building, but this is what it looked like when I was four and a half years old.

Although I only attended one year, I do have some vivid memories of the place. All of my neighborhood friends attended PS 7 or St John's parochial school. My first day of kindergarten—in the classroom whose windows overlook the extended portico seen in this picture—is firmly fixed in my memory as a series of flashing images. I learned to ride a bicycle in the PS 7 school yard, at about age 7; that moment of triumph when I finally caught the knack of staying upright on two wheels has remained with me all my life.

By the time my parents moved in, shortly after World War II, the house had been in existence for 60 years, more or less. It had originally been built for a prosperous middle-class lifestyle of the late 19th Century: not opulent but certainly not down-scale. In my very early youth the bottom level was clearly equipped as a work space. There were two very large built-in soapstone laundry tubs in the kitchen. I have a very early home movie (probably 1951 or a bit earlier) of my father—wearing an apron!—washing a little dog in one of these tubs; and one of my earliest memories is of being bathed in one myself—though not with the dog! There was a sort of "servant's dining area" separated from that part of the basement by a pair of small upright cupboards. I remember a couple of extended-family dinners there (at Thanksgiving or perhaps Christmas) and my third birthday was celebrated in that space: that party is my very earliest memory. My parents had this ground floor space renovated in 1951, and as a 4-year-old I was bitterly unhappy about the proceedings: I told the workmen that "When this is my house I'm going to put it all back again the way it was!" And God knows, if I could, I would.

At the other end of the ground floor there was a coal cellar for the furnace. Although my father converted our house to oil heat when I was very small, I remember seeing coal trucks delivering to the apartment buildings on the other side of Kingsbridge Avenue, and the building "supers" putting out barrels of coal ash and cinders once a week. In winter this debris was spread on the street to give traction for cars. The old coal cellar was later cleaned out, tiled, and a three-quarter bath built into it.

The house had four stories. The bottom was the work space, and the very top floor was the servant's quarters. The latter included a reasonably good sized bedroom room at the front, a short hallway, and at the back a storage closet, what would have been called a "lumber room" in the 1880's.

The owner's family lived on the two floors between. The front of the house was taken up with a large "drawing room" off the entry hallway, and the back part originally was a dining room and perhaps a conservatory in an overhanging structure above the driveway. This floor became the "office floor," where my father practiced. The floor above this was the bedroom floor: there were three bedrooms, two large and one smaller; and a full bathroom with a tub and what may have been the largest flush toilet ever built. A spiral servant's staircase led from the scullery/kitchen to the main floor; a somewhat grander staircase to the bedroom floor; and a steep third flight of stairs to the topmost servant's quarters.

By 1909 the neighborhood was wired for electricity: there are street lamps in the image of PS 7 from that time. But when the house was built in the 1880's it was almost certainly lit by gas. In the upper hallway on the bedroom floor when we lived there was the cut-off-and-sealed stump of a gas line projecting from the wall, which unquestionably had originally fed a light fixture.

This picture of Kingsbridge Avenue was made in June of 1916. I'm not sure exactly what's happening here, but it seems to be some sort of a children's parade. The lady with the baby carriage is standing on the corner of 231st Street. The view is to the north. Two large chimneys are visible, indicated by an arrow: those are on top of my house. There's a wrap-around porch which was later closed in. PS 7 can be seen in the distance. No apartment buildings had yet been constructed on the east side of Kingsbridge Avenue by 1916, but those came very shortly after this picture was made.

This picture of Kingsbridge Avenue was made in June of 1916. I'm not sure exactly what's happening here, but it seems to be some sort of a children's parade. The lady with the baby carriage is standing on the corner of 231st Street. The view is to the north. Two large chimneys are visible, indicated by an arrow: those are on top of my house. There's a wrap-around porch which was later closed in. PS 7 can be seen in the distance. No apartment buildings had yet been constructed on the east side of Kingsbridge Avenue by 1916, but those came very shortly after this picture was made.

The image at right, which was kindly provided by a descendant of Gyulo Armeny (see below for a discussion of this remarkable man) was made about 1946, i.e., about the time my parents bought it. The porches on either side (3117 and 3121) are wood; I remember them that way and remember my father and uncle replacing them with concrete ones. Other than the color and the immense stand of ivy, though, it looks substantially as it was in my time there.

At left is the way the house looked when we lived in it. I took this picture about 1972, from across the street. The oblong windows at the top are those of the original servant's quarters, by that time converted to a bedroom for me. The "turret" to the right is part of 3121. The entrance at left, with a stairway leading up to it, opened into my father's medical office and the two windows framed by ivy were the very front end of his waiting area. In the older image above this was the wrap-around porch, later closed in with bricks. Notice that the color has changed from earlier times.

The final image, below, is from Google Earth and shows the house as it existed until it was torn down. My father sold it in 1981, and the subsequent owner (another physician) sold it again when he retired, to some entity called "Stafford Holdings," who managed both 3117 and 3121 as rental properties. It's considerably the worse for wear, which I suppose was inevitable after some 130+ years. The entire house was demolished in October of 2024 (see below) and the land is now a pay-to-park lot.

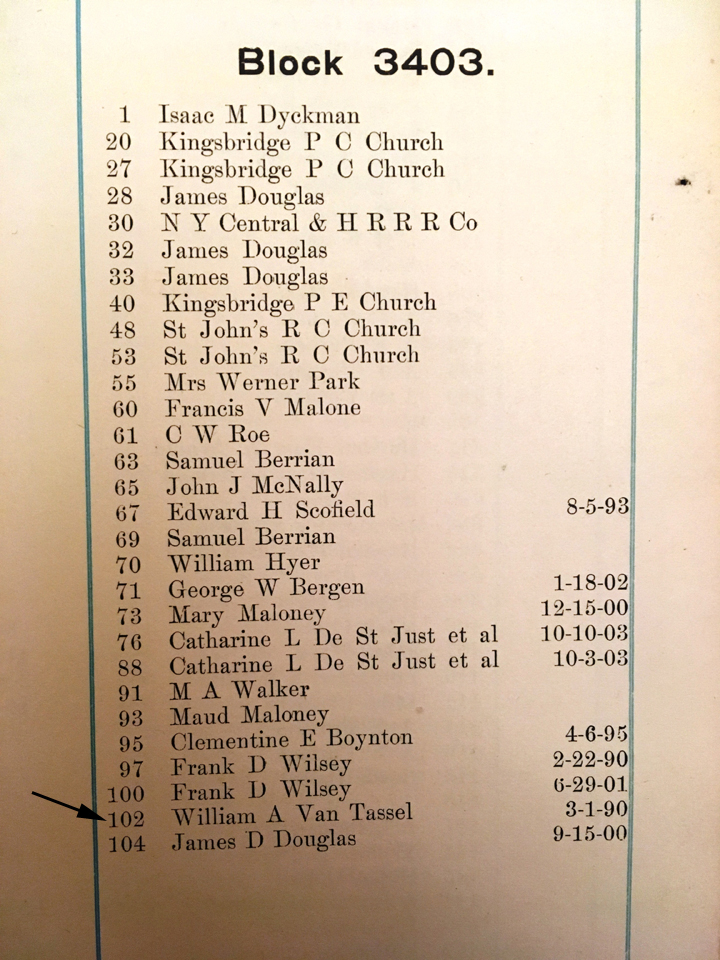

In my attempts to trace the history of the house I've come across a good deal of information about who lived there, though there's much more to be learned. I don't know who the original owners were. In a 1904 City Directory the owner is listed as a "William Van Tassel," who apparently was there as of March 1890. He may have been the original owner. At one time I was told by my parents that they were the third owners of the house, so perhaps this Van Tassel family built it. If in fact it was built in 1888 and he was in possession as of March 1890, likely he was the original owner. The 1890 U.S. Census records have been destroyed, and it's not possible to verify the occupancy from them but the city directory is pretty hard evidence. "Van Tassel" is a far more common name than one might think. I found large numbers of people with that name in Census records from the 1880's onward, some of them in New York City, most of them in the Hudson Valley. This isn't to be wondered at, considering the Dutch heritage of New York.

In my attempts to trace the history of the house I've come across a good deal of information about who lived there, though there's much more to be learned. I don't know who the original owners were. In a 1904 City Directory the owner is listed as a "William Van Tassel," who apparently was there as of March 1890. He may have been the original owner. At one time I was told by my parents that they were the third owners of the house, so perhaps this Van Tassel family built it. If in fact it was built in 1888 and he was in possession as of March 1890, likely he was the original owner. The 1890 U.S. Census records have been destroyed, and it's not possible to verify the occupancy from them but the city directory is pretty hard evidence. "Van Tassel" is a far more common name than one might think. I found large numbers of people with that name in Census records from the 1880's onward, some of them in New York City, most of them in the Hudson Valley. This isn't to be wondered at, considering the Dutch heritage of New York.

For the moment I'm assuming that the "William Van Tassel" listed as the owner in the New York City Directory for 1890 owned the house first and probably had it built. Furthermore, my father once told me the house had been built for a "city official." William Van Tassel was the Postmaster for the Town of Kingsbridge: that would be consistent with the story of its origins. It would have been only about 5 years old at that point, so it seems reasonable to assume he was the original owner. No "Van Tassel" families show up in the Bronx in the 1900 Census records, though a "Caleb Van Tassel" and his large family are found in the 1880 Census records, on Maclean Avenue in Yonkers.

The next family to own it—regardless of from whom they bought it—were the Armenys. They moved in no later than 1904-1905, according to the New York State Census records. My father bought the house in 1946 from Katherine M. Armeny, the widowed second wife of one Gyulo Armeny, a very remarkable man, indeed.

Gyulo Armeny was an immigrant and as good an example of the self-made man who found his fortune in the New World as could be imagined.

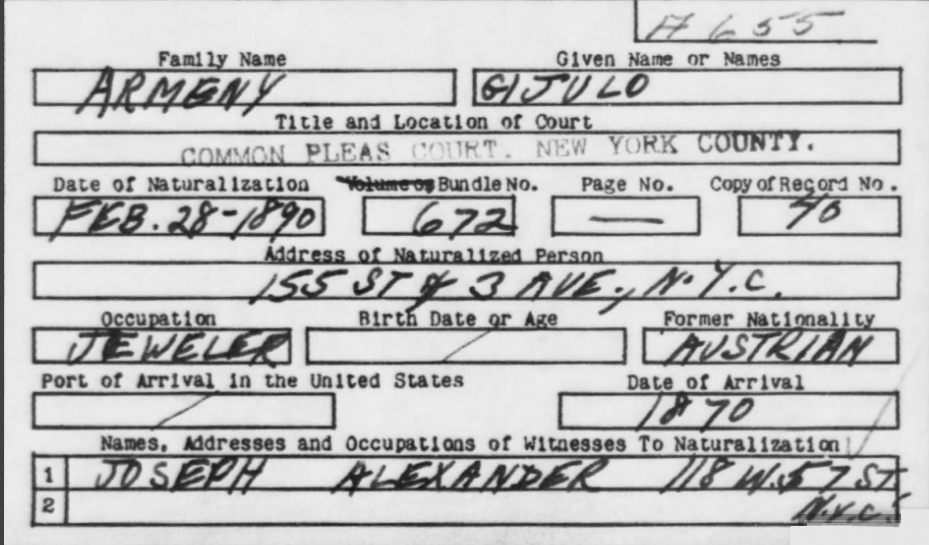

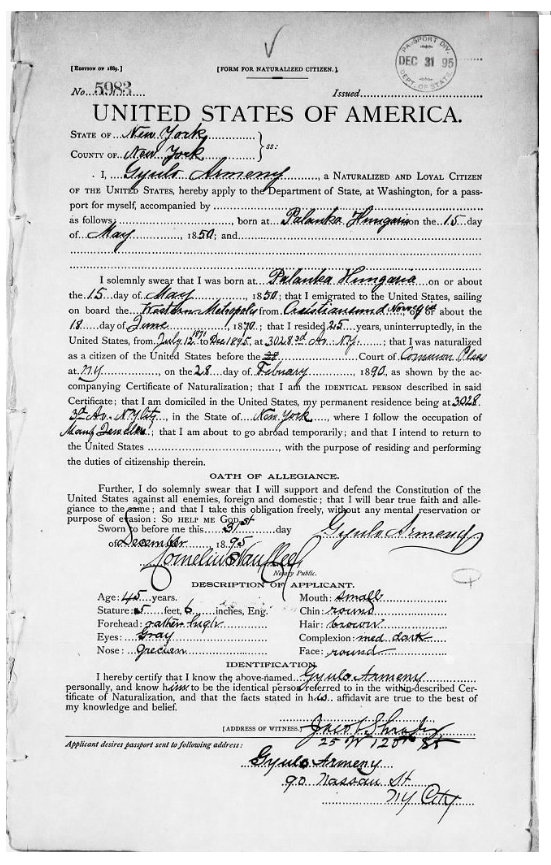

Gyulo Armeny was an immigrant and as good an example of the self-made man who found his fortune in the New World as could be imagined.  He was born in 1850 in Palanka, Hungary. He came to America aboard the side-wheel steamer Western Metropolis, leaving from Christiansted, Norway, landing in New York on July 12, 1870, after three weeks at sea; and I imagine he was heartily glad to see dry land after wallowing across the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean in an obsolete tub. He was 19 when he landed. He'd have passed through the Immigrant Station at Castle Garden (not Ellis Island because that latter station opened in 1892). He was naturalized as a US citizen in the Court of Common Pleas of New York County (Manhattan) on February 28, 1890, giving his occupation as "jeweler" and his residence as "155th Street and 3rd Avenue." His application for a US passport, dated December 31, 1895, gives his address as "3028 Third Avenue." His move to the Bronx came a few years later. The Armeny family was living at 3117 not later than 1905: the New York State Census shows Gyulo and his wife and three children (Percy, Francis, and Marie) in residence.

He was born in 1850 in Palanka, Hungary. He came to America aboard the side-wheel steamer Western Metropolis, leaving from Christiansted, Norway, landing in New York on July 12, 1870, after three weeks at sea; and I imagine he was heartily glad to see dry land after wallowing across the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean in an obsolete tub. He was 19 when he landed. He'd have passed through the Immigrant Station at Castle Garden (not Ellis Island because that latter station opened in 1892). He was naturalized as a US citizen in the Court of Common Pleas of New York County (Manhattan) on February 28, 1890, giving his occupation as "jeweler" and his residence as "155th Street and 3rd Avenue." His application for a US passport, dated December 31, 1895, gives his address as "3028 Third Avenue." His move to the Bronx came a few years later. The Armeny family was living at 3117 not later than 1905: the New York State Census shows Gyulo and his wife and three children (Percy, Francis, and Marie) in residence.

By 1910 the United States Census recorded seven members of the family and a female servant at that

By 1910 the United States Census recorded seven members of the family and a female servant at that  address. One daughter, Marie, was born in 1904; and Eustace Armeny was born in 1907, the youngest son of Gyulo's second set of children. The 1930 US Census states that the daughter Kathryn was born in 1914. Given the maternity practices of the day it's a virtual certainty that at least two of the Armeny children were born at home; depending when the family actually moved in, Marie may have been born there as well. Living with Gyulo in 1920 were his wife, and five children: Percy, Francis, Kathryn, Marie, and Eustace. One "Wale Bordas, female, age 23" is listed as a "servant" in the Census records: she undoubtedly lived in the room on on the top floor.

address. One daughter, Marie, was born in 1904; and Eustace Armeny was born in 1907, the youngest son of Gyulo's second set of children. The 1930 US Census states that the daughter Kathryn was born in 1914. Given the maternity practices of the day it's a virtual certainty that at least two of the Armeny children were born at home; depending when the family actually moved in, Marie may have been born there as well. Living with Gyulo in 1920 were his wife, and five children: Percy, Francis, Kathryn, Marie, and Eustace. One "Wale Bordas, female, age 23" is listed as a "servant" in the Census records: she undoubtedly lived in the room on on the top floor.

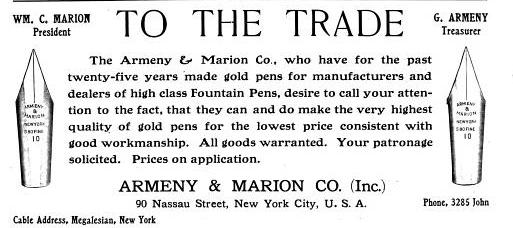

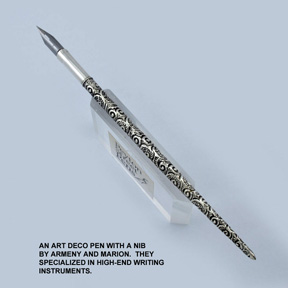

Armeny had learned the jewelry trade after he came to America, and opened a shop in lower Manhattan at 75 Nassau Street. He was very successful and not only was he a jeweler, he was a partner in a firm that made pen nibs. Although nowadays pen nibs might not seem the road to financial success, in the mid to late 19th Century they were an important item. In 1884 Armeny partnered with one William Clayborn Marion to found the firm of Armeny and Marion, makers of pen nibs "To The Trade." They leased space in and later bought, a building at 90 Nassau Street. This building survives to this day and is known as "The Armeny Building."

In keeping with his occupations as a jeweler and pen-maker, Armeny held three US patents. Patent #66577 was for "An apparatus for melting iridium" filed jointly in 1901 with Marion. Patent #677613, for a "Diamond polishing machine," was granted in 1902, to him alone. Patent #697230 was for a "Diamond cross-cutting machine," also granted to him, in 1902, as sole inventor. (Interestingly, a patent search reveals one "Percy Armeny" as the holder of several patents, also related to jewelry: this is undoubtedly Gyulo's son who clearly entered his father's business.)

Although he was certainly well known in the field of pen-making, Armeny always referred to himself as a "manufacturing jeweler." He owned some turquoise mines in the southwestern United States during a period when this stone was very fashionable in upper crust society. He was well known enough, and respected enough, in the jewelry business to be mentioned several times in The Jeweler's Circular, a major trade publication of the day. After his death (of which more anon) his widow Katherine was embroiled in a lawsuit over the dissolution of the Armeny & Marion partnership, involving the very substantial sum of $25,000; a lot of money in 1920! By the time this lawsuit was filed in October of 1920 (with Gyulo's son Francis representing the estate and with his widow Katherine as his Executrix) Gyulo was dead.

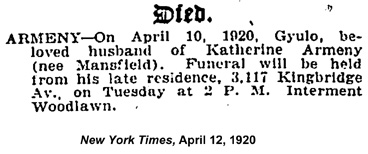

He died on April 10, 1920, of gangrene. His death was noted in detail in The Jeweler's Circular, not surprising given his prominence in the field. The obituary notice included his home address as the place of his death: 3117 Kingsbridge Avenue! The New York Times of April 12, 1920 also indicated that his funeral was held in the house.

He died on April 10, 1920, of gangrene. His death was noted in detail in The Jeweler's Circular, not surprising given his prominence in the field. The obituary notice included his home address as the place of his death: 3117 Kingsbridge Avenue! The New York Times of April 12, 1920 also indicated that his funeral was held in the house.

I don't have any doubt that Gyulo died in the master bedroom, the one my parents used when we lived there; and that his funeral was held in the drawing room on the main floor which later was the waiting room to my father's medical office. I have not obtained a copy of his death certificate (yet) so I don't know the actual cause of the gangrene, but in those pre-antibiotic days it could have been a wound that was infected, or it might have been secondary to diabetes; I'm guessing the latter. He'd made his will (see below) a little less than a year before his death; perhaps he saw it coming and wanted to "have his affairs in order."

There was—more or less predictably—another lawsuit after he died. This one resulted from the fact that Gyulo had been married before and had actually fathered nine children: four by his first wife and five by Katherine. The record of the Court's judgment reads:

Surrogate's Court of the City of New York, Bronx County

120 Misc. 505 (N.Y. Misc. 1923)

MATTER OF GYULO ARMENY

The testator executed his will on May 22, 1919, and died on April 10, 1920. He left him surviving his wife, four children by a former marriage and five children by his second marriage. In his will he gave and bequeathed to his wife the sum of $3,000, to two of his daughters $1,000 each, to another daughter $3,000, and to a son $10, the four children being the issue of the prior marriage of the decedent. [Emphasis added]

He then gave all the rest, residue and remainder of his property "both real and personal and wheresoever situated" to his wife and explained that he had made no provision for the children of his second marriage because he had full confidence that his wife would do what was best according to her judgment.

The question involved is whether the pecuniary legacies mentioned are chargeable upon the real estate of which the decedent died seized. If they are not, they cannot be paid because the personality of the estate appears to have been exhausted through the payment of debts.

After due consideration, I am satisfied that this decedent intended to have the legacies paid out of his whole estate and made no distinction between the personal property and real estate and that the personal property being exhausted, the said legacies are payable out of and chargeable against the real estate.

The financial condition of the decedent at the time that he made the will was such that if all of his debts had been paid, his personality would have been insufficient to pay any part of such legacies. The court is warranted under circumstances such as these in considering the financial condition of the testator at the time he made the will in order that his intent may be ascertained and given effect....The testamentary dispositions adverted to could not be carried out if only his personal property was used for the purpose, and this must have been known to him when he made his will. I am not warranted in reaching a determination which would deprive the legatees of their legacies and impute to the testator testamentary dispositions which he knew could not be carried out, especially as the same were made, not to strangers, but to his wife and some of his children.

I'm no attorney but I read this document to mean that the four children from his first marriage received money that had to come out of the "real estate" he owned, presumably including the house at 3117 Kingsbridge Avenue. Katherine would had to pony up a total of $5010 for Gyulo's children by his first wife. His children by Katherine were left zilch, although she got the house. How Katherine paid this sum, which would have been a significant amount in 1923, I have no idea. Perhaps she took out a mortgage? Assuming the house wasn't already mortgaged, of course; $5K would likely have bought the entire house in 1923. Gyulo owned other real estate as well, which might have covered the expense.

Katherine was born in 1874. In 1946 she'd have been 72 years old, and had been at 3117 for more than 40 years. I imagine she was ready to sell, especially if she'd had to mortgage the property to pay off her husband's first brood. My father, fresh out of the Army, may well have come along at exactly the right time, and the house was suitable both for raising his family and running his practice. In late 1946 my elder sister was 4 years old and I was not yet even "in the pipeline," so to speak, let alone my three younger siblings. But no doubt there were plans. Once my father told me that living and working in the same house wasn't "ideal," but he and my mother made it work and did pretty well. He retired in the early 1980's, and sold the house to another physician as a going concern, complete with patient records and an X-ray machine that may have dated from the First World War, but it still worked.

My father (at left, in 2004) was simply "The Doctor" to Kingsbridge residents. He and my mother ran the sort of one-man practice that has more or less vanished today, and could never survive in the current corporate-style environment of American medicine. He was, in truth, the last of the "Marcus Welby" type of physician. Proof of his importance and standing in Kingsbridge is that when he died in 2009, at the age of 94, he had been retired and gone from the community for nearly 30 years: yet close to 80 of his former patients, virtually all of them geriatrics, attended his memorial service in St John's Church. I imagine some of those who attended were babies he'd delivered, in fact.

Doing the research for this essay I came across some interesting items that I never expected, mostly in the form of old photos. When I lived in Kingsbridge there was a department store on 231st Street, "Fuhrman's." Its roots in the neighborhood go back much farther than I was aware, as is evidenced by this image that dates from some time in the later 19th Century, probably before the annexation period.

Doing the research for this essay I came across some interesting items that I never expected, mostly in the form of old photos. When I lived in Kingsbridge there was a department store on 231st Street, "Fuhrman's." Its roots in the neighborhood go back much farther than I was aware, as is evidenced by this image that dates from some time in the later 19th Century, probably before the annexation period.

Another picture that brought back memories was the one below. It is of the intersection of Riverdale Avenue and 230th Street, taken about 1923. The small square building at the right of the picture no longer exists, but it was there at least as late as 1981. It was a veterinary clinic run by a Dr Fletcher. Two of my family's dogs, Penny and Dante, died in that building, twenty years apart.

As I have been writing this piece I've been wondering why I felt the need to do so. Most likely I'll never see 3117 Kingsbridge Avenue again—and considering what has happened I don't want to—but as Oliver Wendell Holmes put it:

Where we love is home,

Home that our feet may leave, but not our hearts.

—"Homesick In Heaven," Stanza 5

I am now in my eighth decade on this planet. My feet left Kingsbridge Avenue long ago, but as Holmes says, my heart never left. We are all shaped by the circumstances of our lives and upbringing: I can't eradicate those things from my mind and personality. I have too many memories, good and bad, of that place and time for Kingsbridge not to be thought of as "home" still. Over the years I've traveled a lot, lived in different regions of the US, visited many, many countries, and have long been solidly established in a place that's as utterly unlike the Kingsbridge in which I grew up as could be imagined. Yet I have never truly felt that any of the places where I've lived were home in the same sense.

Kingsbridge is very, very different today than it was 60-odd years ago but there are some similarities. The working-class Irish-American/Italian/Jewish mix of residents has been supplanted by an influx from the Dominican Republic and other Third World countries, so even though its ethnic character has changed, it's still a place where immigrants settle. The shops and small stores along West 231st Street have changed hands and in many cases have changed their nature but it's still possible to live a life entirely within the neighborhood, finding all necessities within walking distance: as my late mother would have put it, "On the Avenue."

My house was there for more than 130 years, and it was my fervent hope that it would remain for many years longer. It was not to be. A great crime has been committed and the building demolished to make way for something else.

POSTSCRIPT: The Evil Day Near At Hand

I wrote the essay above a couple of years ago, and I'm sorry to say I was around to see the end of my house. In late 2024 my brother sent me an e-mail with the images shown below of the house in its death throes. It is horrifying and depressing, something I had hoped would happen after I'd died.

Here's what he had to say:

I just returned from a visit to the old neighborhood. Both the old neighborhood, and worse, our childhood home on Kingsbridge Avenue are no more. The attached photos speak for themselves.

The entity that owned the house is something called "Stafford Holdings," who have in fact owned it since the doctor who succeeded my father sold it well over a decade ago. It was then turned into rental units, which didn't do the building any good. But it was habitable and inhabited at least as late as March 2022. This situation has arisen since then and it's obvious that Stafford Holdings—whose offices are around the block on 231st Street—always intended to demolish the house and do something else with the property. It might have been "affordable housing," what we used to call "The Projects." That would have done Kingsbridge even more harm than what actually happened next.

I'm unable to describe the depression and anger this development has brought about in me. That house stood for over 135 years. I recognize it isn't a "national monument" but it's significant enough to me for me to feel betrayed and saddened. I know now, after 78 years on this Godforsaken planet, that sooner or later you will lose everything you love.

ADDENDUM: October 26, 2023

A demolition permit, #220749224, was issued December 16, 2022.

ADDENDUM: October 5, 2024: The End Of The Story

Today I received an e-mail from someone with whom I grew up, someone I have known all my life. He sent me this message:

I feel compelled to confirm that 3117 is no longer there. When walking to the Garden Gourmet I used to be able to see the chimney from West 232nd Street and Corlear Avenue. Today something seemed missing. I take the bus home, and as we passed Kingsbridge Avenue I could see that it was gone.

Coda

So it has happened. That house stood for 136 years; it has seen births and deaths, good news and bad news, youth and old age, and a whole lot of Kingsbridge history. There is nothing left but a vacant lot. A great crime has been committed. Ave atque vale.

I am indebted to the Kingsbridge Historical Society for these three images.

The End

The images below, taken in July of 2025, show the place where my house used to be. Everything that was there is gone: not just the house but the memories, hopes, successes and failures of those who lived, died, and worked there. These pictures come from the NY City Department of Buildings, which at least had the decency to issue an order that the owner stop using the site as a commercial parking lot because it's in a residential neighborhood. I have no idea what will come next but it doesn't really matter any more.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Much of the substance of this essay comes from two books by the late William A. Tieck (1906-1997) who was Pastor of St Stephen's Church. Reverend Tieck came to Kingsbridge in 1946 and lived there the rest of his life, becoming more or less the official historian of the area, and the author of two books: Riverdale, Kingsbridge, and Spuyten Duyvil and Schools and School Days in Riverdale, Kingsbridge, and Spuyten Duyvil. Reverend Tieck interviewed long-time residents of the area and collected numerous images from them that he used in the books. Thanks to the Interlibrary Loan section of the Virginia Tech Libraries I was able to obtain copies of these two rare books.

Another valuable source was the 1887 book History of the Town of Kings Bridge, Now a Part of the 24th Ward of New York City, by Thomas H. Edsall, a member of the New York Historical Society. Mr Edsall's book has many details of the colonial-era Town of Kingsbridge, including information on the retreat of Washington's army.

I must also acknowledge the invaluable help of the New York Historical Society and the New York Public Library. Both these institutions maintain documentary collections of city directories, old maps, and other historical records that chronicle the story of Kingsbridge. Their incomparable map collections are beyond any praise I could give them; librarians are the custodians of our past and the gatekeepers of our future.

The web sites Ancestry.org and FamilySearch.org gave me access to the records of the various Federal and State Censuses, enabling me to reconstruct the timeline of the house and the Armeny family.

And I would be remiss if I didn't point out that it is simply astonishing what kinds of information can be obtained through the Internet. With the exception of the physical volumes of Reverend Tieck's work, nearly everything was accessed on line. The entire history of the entire world will someday be reachable through a computer interface; whatever happens in this world we no longer need to worry about the loss of knowledge bringing about a new Dark Ages. It's all on line, or soon will be.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |